Little wonder that Boom Supersonic founder Blake Scholl describes the Oct. 7 rollout of the company’s sleek XB-1 demonstrator as “a little surreal.” Since creating Boom in 2014 to bring back supersonic civil flight, Scholl’s ambitious plan has been derided as crazy by some and unrealistic by others.

Now, with a completed aircraft set to begin ground tests in the coming weeks and design work transitioning to the follow-on Overture airliner, Boom’s vision is gaining ground and—just as important—credibility.

- One-third-scale XB-1 ready to begin ground tests

- Formal launch of Overture airliner set for 2022

Although the 71-ft.-long, delta-wing XB-1 trijet looks to have more in common with a high-speed fighter than an airliner, the completed demonstrator has already proven to Boom’s backers that it has the design and manufacturing capability to produce the first privately developed air-breathing civil supersonic aircraft.

But the next real test will be in taking flight. Comparing the XB-1 to the pioneering role played by the Falcon 1 launch vehicle for SpaceX, Scholl says the major challenge will be proving the baseline aerodynamics of Boom’s ogive delta wing and engine inlet design across the low-speed, transonic and high-speed envelopes. Flight tests will begin in Mojave, California, later in 2021 following initial ground tests at Centennial Airport near Denver.

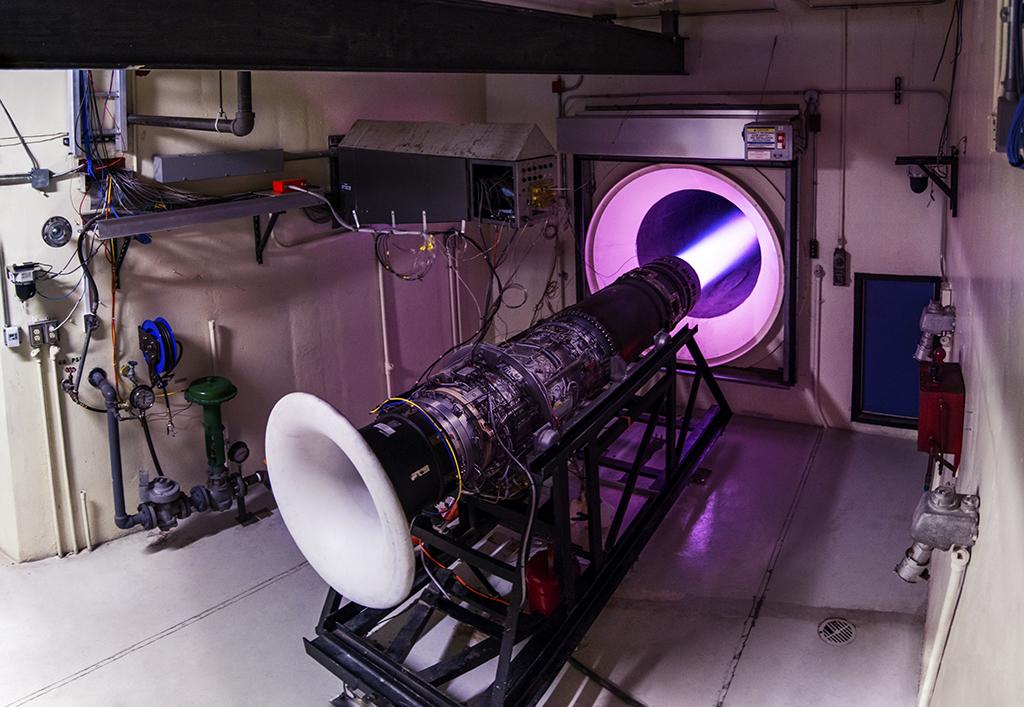

Internally nicknamed “Baby Boom,” the XB-1 will be put through an initial battery of 36 major ground tests ranging from hydraulic system checks and engine runs to failure modes and ground vibration tests. “We’ll do taxi tests here in Colorado, and then we take the vertical tail off, put it on a truck and take it down to Mojave. Then we put the throttle forward and go fly, and that’ll probably be later next year.”

Acknowledging his earlier overoptimistic schedule and “many setbacks and roadblocks” along the way, first flight is provisionally slated for “something like the third quarter,” Scholl says. “I don’t want to promise anything too specific, and then we’ll be supersonic by the end of next year.”

A major source of skepticism about Boom during the last six years has centered on the lack of a definitive plan for how to power its supersonic airliner. Three GE Aviation J85s will power the XB-1. But until recently, nothing was known about the engine choices for the Overture. With the recent disclosure that Rolls-Royce has been in talks with Boom for five years and is now the chosen propulsion partner for the airliner, more details are beginning to emerge.

“A few months ago, Rolls had three different engine concepts for the aircraft, and by November we’ll be selecting one,” Scholl says. “We think we know what the winner is already, actually. But we’re kind of dotting the ‘i’s and crossing the ‘t’s and making sure that we’ve got that right.” Few specifics are known, but Scholl says all the options are medium-bypass midthrust derivatives of existing cores. “The options are a completely off-the-shelf core, an upgraded core or a photo-scaled core,” he adds. All will be adapted with a new low-pressure system, distortion-tolerant fan and exhaust.

With engine plans firming up and the XB-1 ready for testing, Boom’s schedule for the Overture is also coming into sharper focus. Based on lessons learned from the demonstrator, final configuration freeze is targeted for the end of 2021. The program will be officially launched in 2022, coinciding with groundbreaking for the as-yet-unnamed production site. “In 2023, we’ll start building the first parts and tools, and then rollout of Overture is in 2025. First flight is 2026,” Scholl says.

“Then the question becomes, how long does flight test and certification take? The [Airbus] A350 did it in 18 months. I suspect that would be pretty sporty for us, given the airplane and that we’re in the post-737 MAX era,” he adds. At the rollout, entry into service was given as 2029, but Scholl says: “Our commitment is to carry passengers by the end of the decade—and there’s some margin in there.”

Boom also plans to whittle down its list of 15 potential U.S. assembly sites to around five finalists by year-end. “If you look at the schedule, we better know where we’re going to be by the middle of next year,” Scholl says. He adds that the final arrangement could include an option for an inland final assembly facility and a coastal site for supersonic flight test and delivery.

Comments

The Overture will therefore be plagued by the same problems that killed the Concorde, the sonic boom and limited ground overflight capability.