Air Canada has 33 Airbus A220s in service from a total order of 60 aircraft.

Canada is often considered a sleeping giant, living in the shadow of its much more populous neighbor south of the 49th parallel. Though it is the world’s second-largest country by area, its population has only just reached 40 million, ranking 37th worldwide, with 85% living within 100 miles of the US border.

Air Canada, with its maple leaf logo, is very much a symbol of its home nation. And like the country, the airline is seeing changes.

Michael Rousseau became president and CEO at Air Canada in February 2021, in the midst of the pandemic, following a long career that included posts as CFO and deputy CEO.

Talking with ATW at the company’s headquarters near Montreal Trudeau International Airport, Rousseau noted the transformations affecting the nation and its airline sector.

Long perceived as a homogenous population, now one in four Canadians are immigrants. The fastest-growing cohort is South Asians, led by a tripling of Indian immigration over the last decade, which has supplanted the Chinese as the second-largest minority population.

“We’re a big supporter of immigration. It benefits Canada and benefits us,” Rousseau said.

South Asia leads Air Canada’s explosive international capacity growth since 2019, with 43%, followed by the Middle East at 33%. The Vancouver hub’s new nonstop services to Singapore and Dubai are just two examples of the carrier seizing the market.

Air Canada’s Indian presence is hobbled by the loss of Russian overflying rights since Russia invaded Ukraine, resulting in the suspension of its Vancouver-New Delhi route and a longer and more costly routing from Toronto. This obstacle leaves an opening for a resurgent Air India. “We’re not happy about Air India taking over our franchise, but it’s a good thing to have them as a strong carrier in the Star Alliance network,” Rousseau noted.

The current restrictions for visitors and flights to mainland China and Russian overflying also imperil the airline’s Chinese franchise. Rousseau describes a mixed picture.

“Canada is starting to talk to China about opening up a little more frequency. They [Chinese carriers] can fly over Russia; we can’t,” he said. “That means we can’t make China from Toronto for the most part, or it’s not economical for us. So how’s that fair?”

Air Canada may be the most-partnered airline in the world.

“When I came along into the alliance world in 2011, we had 19 partners. Now we have close to 40 in our portfolio,” managing director-international network and partnerships Mary-Jane Lorette said.

This mindset to go beyond the Star Alliance and its Lufthansa immunized joint venture (JV) has been critical in securing links to South Asia, the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent through a partnership with Emirates Airlines. According to Rousseau, “It’s been a win-win situation. We give them the ability to move their customers in Canada. And they go into many more markets in India than we could ever go into.”

Air Canada’s significantly bulked-up international markets have “propelled nearly 70% of the year-over-year increase in passenger revenues,” the company reported in its 2023 second-quarter earnings report. The company also reported an operating margin of 14.8% and a C$802 million ($589 million) profit, compared to an operating loss of C$253 million in the second quarter of 2022. Revenue jumped 36% to C$5.43 billion.

International destinations fell from 134 in August 2019 to 109 in August 2023, mainly because low-cost leisure subsidiary Rouge pulled down its Boeing 767 service. But rebuilding is underway, with the announcement or launch of 48 new routes over the last two years. Some new markets, like Vancouver-Bangkok and Dubai, are helping to diversify and counterbalance the typically seasonal patterns that afflict Canadian airlines. However, the peak summer season is growing and beginning earlier and ending later—an opportunity the company is capitalizing on with planned higher frequency and extended schedules.

Sixth freedom flying is an ascendant part of the revenue diversification strategy.

“We sit on top of a market that’s the most active travel market in the world. The US market is 10 times our size. We don’t have to get a lot of traffic moving up from there to catch our international flights for us to make that a very successful flight for us,” Rousseau said.

This is just one of the catalysts for Air Canada’s burgeoning expansion south of the border, with secondary markets like Salt Lake City, Utah, and Orange County, California, joining the map. Air Canada’s JV with United Airlines enjoys a combined 58% share of seats, August 2023 OAG data show, with LCC competitor WestJet a distant 14.5%.

As Air Canada works to fortify its transborder position, new Canadian LCC competitors are joining the already crowded fray. Canada’s domestic market is an oversaturated LCC battleground. Since 2019, two new entrants have joined: Lynx Air and Canadian Jetlines, while Flair Airlines has consolidated its position as the leader. Though WestJet’s ULCC Swoop will be absorbed into its parent, the LCC onslaught continues. Canada’s four principal domestic discounters’ have grown the market share from 4% in 2019 to 21% in 2023.

Air Canada’s biggest emerging threat on the upscale front, however, is the Toronto-based Porter Airlines, with its new Embraer E2 jets, that is challenging the flag carrier on transcontinental runs and in the winter sun Florida markets that are crucial during the weak first quarter.

“Entry of these LCCs with large growth plans and then Porter with an order of 50 planes means, if everything comes to pass, there could be a lot more planes in Canada over the next couple years that will affect the economics of the business. Domestic yields are OK, but they’re not as strong as international yields,” Rousseau said.

Air Canada is using its breakneck international expansion as a cudgel and advantage to counter its domestic contraction to 52 destinations from 61 in 2019, OAG data reveals. The LCCs are the direct and indirect cause of Air Canada’s market share declining from 48% to 40%, with WestJet also seeing a decline from 32% to 27% over the same period.

Rousseau said Air Canada will continue to focus on the three hubs where it dominates: Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver, in provinces where 75% of the population reside.

“You can’t be number one in four hubs,” he said. “We know WestJet will always be the dominant carrier in Calgary, and that’s fine. They’re a good competitor. They know what they’re doing.”

Air Canada’s trimmed domestic capacity is mostly caused by the drastic pulldown in regional flying by exclusive partner Jazz Aviation, operator of Air Canada Express. While mainline capacity recovered to 96% of 2019 levels, regional flying, which accounted for 44% of the company’s domestic capacity in August, is only at 53% of 2019 traffic levels, OAG data shows. Like its regional counterparts in the US, Jazz has pilot-retention problems.

“A Jazz pilot can resign and join someone else, and that pilot has already been scheduled for the month,” Rousseau said. Some pilots are now jumping Jazz’s ship for the lure of flying larger aircraft at higher wages with the LCCs.

Canada’s new flight duty times and rules, established just before the pandemic, caused all airlines to increase the number of pilots to fly the same schedule—an unintended double-whammy consequence.

The apparent knock-on effects are cancellations, reduced frequency, and some small-city service suspensions, though the mainline carrier is mitigating it somewhat by upgauging aircraft. The company is confronting the increased demand and attrition at Air Canada Express by “trying to wait to increase the wage rates,” Rousseau said. Playing in the mainline carrier’s favor is “an attractive up-flow agreement. So they start at Jazz flying 50-75 seaters, and after a certain amount of time, they get to come to Air Canada. As the premier airline in Canada, we had no issue attracting pilots,” he said.

This gives the flag carrier an edge its competitors can’t touch.

“Air Canada is a place pilots want to come because we fly the biggest planes for the most part to the most attractive locations,” Rousseau said.

Air Canada’s 4,500-member-strong pilots union, Air Canada Pilots Association (ACPA), is transitioning over to the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) as it elects to begin negotiating its 10-year collective bargaining agreement (CBA) ratified in 2014, a year early. Rosseau says the company is talking with them, but he doesn’t see the recent blockbuster new contracts in the US as a template.

“I compete in Canada, so I need to be competitive in Canada,” he said, alluding to the newly ratified WestJet CBA as a model versus the richer, new US contracts.

“You have to be careful with the US deals because a lot of it is retro pay,” he said. The company’s massive international growth has translated into quicker promotion to higher paying widebody jobs, “So the pilots all saw tremendous growth aside from the 2% or 3% they’re getting on an annual basis.”

AIRPORT COSTS

Canada’s airport-related costs are among the highest in the world, with airport improvement fees and federal government security fees running up to five times those in the US. Beyond costs, Rousseau sees airport infrastructure as the most pressing pinch point. Unlike in other parts of the world, Canadian airports are not taxpayer-supported but instead have a user-pay model.

“It worked fine up until the pandemic. And then there were no passengers during the pandemic. So, the airport authorities had to take on over $3 billion in debt to fund their losses over that period. As a result, they don’t have the money in the short term to go back and do the infrastructure projects they were thinking of doing,” he explained. “I would like the Canadian government to step in and help accelerate infrastructure improvements at the airports in Canada.”

Rousseau considers this an urgent matter of national economic importance.

“Air Canada generates 2% GDP. We’ve got 37,000 people working for us. There’s typically a ratio of four extra jobs to each job that we have. Our ability to grow is a function of the airport infrastructure improving over the next couple of years,” he said.

Shortages of air traffic controllers at Nav Canada are abating as new hires cycle through training, but it will take time to bring them up to speed.

“Our [post-pandemic] ramp-up was much steeper than the US ramp-up. And so that put tremendous pressure on the ecosystem—not just the airline, but all the partners we’ve worked with,” Rousseau said.

These issues manifested in Air Canada’s on-time performance (OTP) over the summer, ranking last among North American carriers. As summer ends, the airline saw improvements, returning to the “great operational performance we had in April and May.”

But Rousseau suggests there’s more to the story than just numbers.

“We’re not Delta. They block at 85. We block at 50 to 60, so we will have OTP that is not the top of the market,” he explained. “We don’t want to be the bottom, but we’re going to be somewhere in between, basically.”

The balance between on-time performance and revenue efficiency or utilization of assets is a calculated decision.

One of Air Canada’s most prized assets is its Aeroplan loyalty program, which it bought back from Aimia five years ago for $330 million. In an uncharacteristically Canadian boast, Rousseau said, “I would put Aeroplan up against any program in the world. We added a whole bunch of benefits and partnerships to make it much more valuable to customers. So far, it’s knocking it out of the park.”

Particularly in the US, loyalty programs are huge, high-margin billion-dollar profit drivers, but Canada’s slightly lower merchant commission rates result in a different market and model. Air Canada doesn’t break out revenue and membership numbers but says the retooled program is setting records and provides a true edge that the competition can’t match.

The airline also trumpets its status as the only international network carrier in North America to receive a 4-star rating from Skytrax. Upgraded amenities in its Signature branded business and premium economy cabins are attracting business and premium-seeking leisure travelers. The airline is deploying the IATA New Distribution Capability in marketing its content, but not at the expense of corporate sales.

“We have watched what American Airlines has done in the last little while. We’ve taken a much different approach. We spend a lot of time with both corporate customers and the trade,” Rousseau said.

CARGO OPS

In a case of what’s old is new again, Air Canada has found another source of revenue diversification. During the pandemic, the airline pioneered “preighter” aircraft by removing seats on the main deck to move essential freight, operating 10,200 cargo-only flights.

“It kind of opened up our eyes to the cargo business. It’s been 15-20 years since we ran a freighter business. We said, ‘Maybe we can run this business successfully,’” Rousseau said.

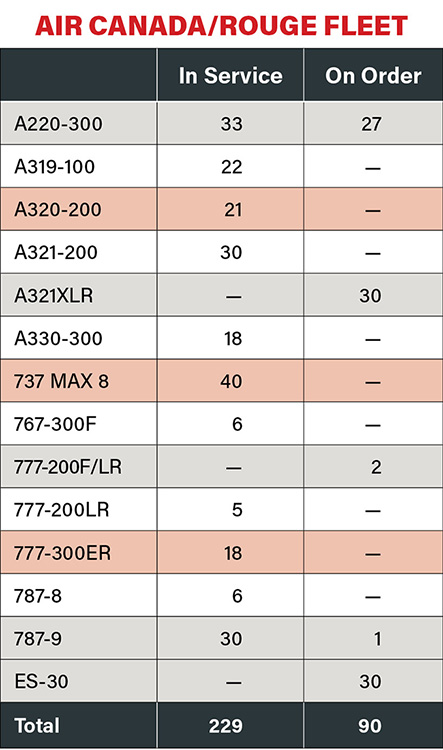

Air Canada has six Boeing 767 dedicated freighters in its operating fleet, with four 767Fs and two new-build 777F’s on the way. Rouge is providing the low-cost 767 feedstock for conversions as all 25 were retired in 2021.

Rousseau is unfazed by the current softness in the cargo market. “You got to play a long game in this business,” he said.

Air Canada has no plans for the downsized Rouge to reenter the European and South American markets it exited with the withdrawal of the 767s.

“We believe that mainline can more than satisfy the vast majority of markets that we want to go to,” he said.

Rouge is more about density and higher utilization of assets than lower labor costs. The brand has been shrunk, somewhat de-seasonalized, and refocused on the US, Caribbean, Mexican and Central American leisure markets. Thirty new Airbus A321XLRs, expected to begin arriving in 2025, may allow the company to bring back some former Rouge service.

FLEET PLANS

Air Canada’s orderbook is devoid of splashy new fleet announcements. The company’s last top-off order for 15 Airbus A220s, built in Mirabel, near Montreal, for a fleet total of 60 is 27 aircraft away from being fulfilled. The airline and its customers “love the aircraft,” Rosseau said, but they aren’t immune from the Pratt & Whitney GTF engine issues, with five airframes grounded in August.

The airline also has an order for 30 ES-30s, a 30-seat electric regional aircraft being developed by Swedish manufacturer Heart Aerospace.

When asked about any upcoming RFPs for more MAXs, A220s or 787s, Rosseau was coy.

“It’s a combination of growth and replacement. It really depends on how the world evolves over the next little while,” he said.

The understated Canadian gets most animated describing the flag carrier’s internally developed ECX program designed to focus on the customer experience and solidify its self-proclaimed position as the “best airline in North America.”

“We were pretty good at customer service, but we want to take it to another level,” he said.

The four-pillared initiative puts the customer at the center of everything the airline does: strategy and roadmap, on-time performance, disruption, and engagement of employees. It is the human element that is the catalyst for everything else.

“We have 37,000 incredible employees that want to do a good job. We must give them the ability to do that,” Rousseau said.