As it undergoes a company restructuring, a much smaller South African Airways is navigating a new path forward.

South Africa’s airline landscape has been through a whirlwind of change in recent years. Following multiple airline failures and the radical downsizing of national carrier South African Airways (SAA), privately owned Airlink and FlySafair have emerged as market leaders.

The reshaping of the South African market saw a series of airlines go through business rescue, which is roughly akin to administration proceedings or Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. SAA suspended scheduled flights from March 2020 for 18 months. Around that time, state-owned regional airline SA Express halted operations, followed by SAA LCC subsidiary Mango in July 2021 and privately owned Comair in May 2022. A much smaller SAA resumed flights in September 2021 and Mango may still fly again, but its future hangs in the balance.

After numerous rescue attempts, SA Express and Comair appear to have permanently disappeared. Of all the exits, Comair’s failure was perhaps the greatest shock because before its entry into business rescue in May 2020, the carrier had been profitable every quarter for 73 consecutive years. Former Comair CEO Gidon Novick has added to the market shakeup, launching a new virtual airline called LIFT in December 2020 using aircraft operated by Johannesburg-based Global Airways. Novick knows the market, so LIFT is one to watch, but it remains one of the smaller players.

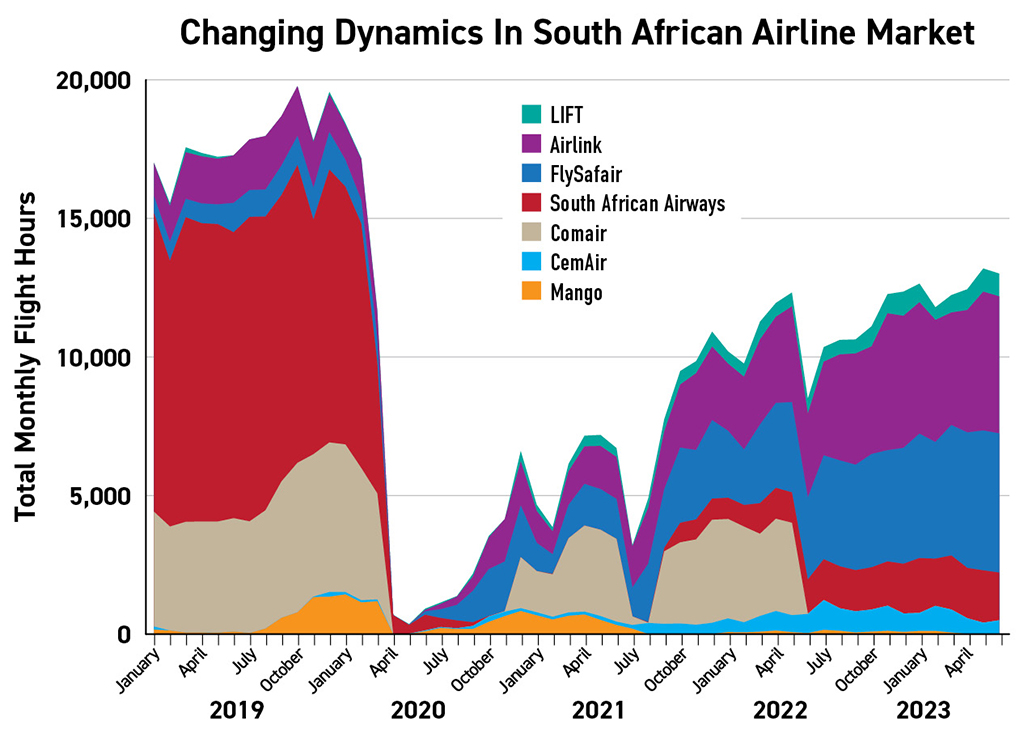

Aviation Week Network’s Tracked Aircraft Utilization tool shows the extent of these market changes. At first glance, the most noticeable shift is that South Africa’s largest airlines now perform 37% fewer flying hours than they did in October 2019. However, the key difference is who is performing that flying.

Before the pandemic, SAA led the way, peaking at around 11,000 monthly flying hours. Comair ranked a distant second, flying about half the hours of SAA. At that time, Mango, Airlink and FlySafair were all neck-and-neck, with each operating less than a fifth of SAA’s total.

Rise Of The Underdogs

In a complete turnabout, Airlink and FlySafair now lead the pack with around 5,000 monthly flying hours each, followed by SAA at around 2,000 hours. The market has effectively consolidated down to three key players, with longstanding regional CemAir emerging as a fourth contender, alongside LIFT.

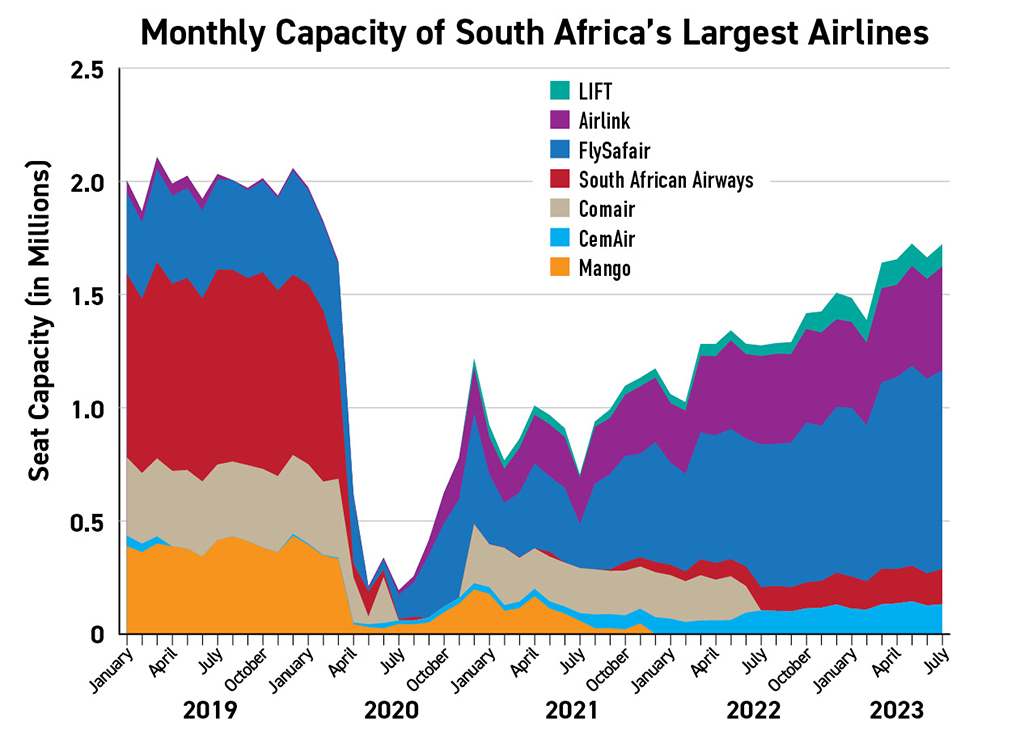

FlySafair operates 32 Boeing 737s, while Airlink’s 62-aircraft fleet mainly comprises Embraer ERJs and E-Jets. This means that FlySafair is offering twice as many seats as Airlink, even though their flight hours are evenly matched. However, it is worth noting that Airlink is now double the size of SAA in terms of seat capacity.

Unusually, in 2020, FlySafair urged its competitors to resume flights after its share of domestic seat capacity tripled from 24% to around 76%.

“We’re operating at full tilt. We need our competition to return,” FlySafair chief marketing officer Kirby Gordon said in October 2020. However, since then, Comair and Mango have both halted operations.

“Airlink is in a far better position now than we ever have been,” Airlink CEO and managing director Rodger Foster told ATW. Airlink also gained from Comair’s demise, picking up a British Airways (BA) codeshare in February 2023 that generates significant feed through Johannesburg and Cape Town. Previously, Comair had been a long-term BA franchise partner, operating flights in BA livery.

“The South African market is completely different from what it was before we went into COVID lockdown,” Airlines Association of Southern Africa (AASA) CEO Aaron Munetsi told ATW. “However, we have also seen the resilience of the remaining airlines. They have stepped up their operations by increasing the frequencies that they operate and increasing the capacity that they deploy. We’ve seen quite a significant increase in new aircraft.”

The Southern African airline lobby group represents 16 carriers, including Airlink, FlySafair, LIFT, Mango and SAA. Munetsi also knows the inner workings of SAA, having spent over two decades working for the national carrier until May 2019. Munetsi believes the new SAA is “fundamentally different” from its former self.

SAA entered business rescue in December 2019, suspending scheduled flights when the pandemic hit in March 2020. The flag carrier only resumed operations 18 months later, in September 2021, as a radically downsized operation.

“SAA should be dead,” the government said in a May 2023 budget update. “Its assets should have been sold, and it should have been in liquidation, but through the determined effort of government SAA has been saved.”

To put SAA’s restructuring in context, the carrier’s summer 2023 capacity is 81% lower than for the summer 2018, and it now has a fleet of just seven aircraft (five Airbus A320s, one A330 and one A340) versus 49 aircraft before the restructuring. This winter, SAA will return to long-haul operations for the first time in three years, serving São Paulo from Cape Town and Johannesburg. SAA interim CEO John Lamola said this decision followed a “rigorous analysis” of route viability. “Sustainability has been at the heart of SAA’s approach since our restart,” he said.

SAA used to fly seven intercontinental routes from Johannesburg, along with an extensive regional network. Today, it operates just 13 nonstop short-haul routes. However, SAA recently secured government approval to add six more aircraft to its fleet, five A320-family aircraft and one A330. This will help SAA grow to 20 destinations by March 2024, including the new São Paulo links.

Munetsi at AASA said SAA has cut costs and is playing to its strengths, using airline partnerships to expand its reach. “They’re not going to go everywhere that they used to go,” he said. “They are making sure that they are operating at optimum levels on those destinations. Only after that will they start thinking of expanding.”

SAA’s ownership is also set to change, with the introduction of a new strategic investor. Munetsi believes this will give SAA’s management more control over the day-to-day running of the airline, with the government becoming a less-involved shareholder.

Takatso Consortium was named as the lead bidder for a 51% stake in SAA around two years ago, with the government planning to retain a 49% stake. The consortium comprises three private-sector companies, African infrastructure investor Harith General Partners as the majority shareholder, along with South African capacity provider Global Aviation and Syranix as minority shareholders and technical partners. The proposed merger of SAA and Takatso was conditionally approved by South Africa’s Competition Tribunal in July 2023, but the long-awaited go-ahead comes with conditions.

South Africa’s competition bodies were unconcerned about Harith’s shareholding in Lanseria Airport, which is Johannesburg’s secondary airport. The sticking point was that Global Aviation trades as Global Airways, which is the AOC holder and wet-lease provider for SAA’s new rival, LIFT. Meanwhile, Syranix is a management services provider that co-owns the LIFT trademark. This raised a red flag for the South African Competition Commission.

“The merger will likely facilitate the exchange of competitively sensitive information between SAA and LIFT, through Global Aviation and Syranix having shareholding,” the Competition Commission said in its May 2023 recommendations. As a condition of the merger, the commission advised that Global Aviation and Syranix should completely divest from Takatso for the merger to go ahead. After some initial resistance, the commission said Takatso agreed to these terms, along with a stipulation that there will be no merger-related retrenchments. In its final July 25 ruling, the Competition Tribunal upheld these conditions.

SAA is currently owned by the South African government, specifically the Department of Public Enterprises (DPE). South African public enterprises minister Pravin Gordhan described the tribunal’s decision as “a significant step” in SAA’s recovery. The DPE is working with Takatso to finalize other “critical regulatory requirements,” which are needed to complete the transaction.

New Friendships

In the meantime, SAA has delayed plans to create a pan-African airline group with Kenya Airways. It is notable that Kenya Airways is a SkyTeam global alliance member, while SAA belongs to the Star Alliance. The two African airlines announced their cooperation in September 2021 and finalized the agreement in November 2021.

Specifically, Kenya Airways and SAA are seeking antitrust immunity to leverage their respective Nairobi and Johannesburg home hubs, with ambitions of co-founding a pan-African airline group. This was meant to happen in 2023, but it has been pushed back to 2024, giving both carriers time to focus on their restructurings.

“It’s hard enough to bring two airlines together, but once we’ve done that, then it should be easier for us to incorporate others,” Kenya Airways group managing director & CEO Allan Kilavuka said in May 2022.

Under the original vision, the strategic cooperation had three phases. An initial phase, scheduled for completion by the end of 2022, was focused on quick wins, such as reciprocal lounge access. A second phase involved the practical design of the new pan-African airline group, including group structure, ownership, network and fleet cooperation. A third phase—the pan-African airline group rollout—was planned from late 2023.

“They are currently at phase two of the implementation process, which involves putting modalities in place for a joint venture,” a Kenya Airways spokesperson told ATW earlier this year. “Currently the two airlines are restructuring, and this includes things around fleet rationalization. The plan is to have this completed by 2024. Once this process is finalized, by 2024, then the formation of the pan-African airline group will happen.”

A West African airline partner is likely to be among their eventual targets because Kenya Airways is based in East Africa and SAA’s hub is in Southern Africa.

“Kenya Airways has their own complexities that they are dealing with internally,” Munetsi said. “I think that takes away the momentum, in terms of how they would want to come to the party. At the same time, SAA is grappling with their own equity partnership. And, because of that, both sides are not moving as fast as they should. The second thing is that the environment itself is dynamic. While they are grappling with all those issues, competition is already ramping up, so their plans might be overtaken by events. I’m not saying they won’t end up consummating their relationship; they probably will but in a different form.”

Questions also remain over whether SAA’s LCC Mango will ultimately make a comeback. Mango has not flown since July 2021, when it entered business rescue. An investor was ready to buy Mango back in July 2022, but a year later the government is yet to sign off on the sale. Once again, the deadlock appears to be over whether Mango’s buyers are a competitive threat to SAA.

In February 2023, Mango business rescue practitioner Sipho Sono took legal action against the government for hindering the process. The delayed case was finally heard on May 29 and 30, but the judgment has been reserved. Meanwhile, Sono has been fighting to get Mango’s licenses reinstated, after they were cancelled in February, with further news expected after a July 18 court hearing. Sono is also fending off a challenge to Mango’s business rescue plan from one of the airline’s creditors, Aviation Co-Ordination Services.

Munetsi notes the Mango process was going “very, very slowly,” but believes the brand could still be saved. “I don’t think there’s an intention for them to completely kill Mango,” he said. “I don’t know what it will finally end up with, but I don’t think it will completely disappear from the market.”

In late June, Sono once again warned that the buyer could withdraw if the issues were not resolved soon. This would result in Mango being wound down—and yet another loss for the evolving South African aviation landscape.

“We have now come up with a completely new hybrid community of airlines,” Munetsi said.

Listen to the author discuss the South African air transport market on the ATW Window Seat podcast at bit.ly/3OSa0Lv.