Commentary: Six Must-Do’s For A Startup Low-Cost Carrier

Arvind Chandrasekhar and Wasiq Khurshid

As the industry recovers from the COVID-19 crisis, it is clear that LCCs and hybrid LCCs have shown more resilience.

LCCs fare better than most full-service carriers in turbulent market conditions for a few stand-out reasons. Their lack of reliance on hub structures allows for dynamism in network management and resource allocation. Their networks are usually domestic or continental in nature, and therefore are minimally disturbed by geopolitics that affects intercontinental traffic. LCCs’ dependence on corporate travel is limited, and they don’t stand to lose a considerable proportion of their passengers and revenues during financial downturns. LCCs also tend have leaner organizational structures to curb excess overhead costs.

Lufthansa Consulting examined 18 markets across five continents over the last 20 years. The research also spanned a variety of competitive situations facing a new entrant, including but not limited to state carrier monopolies, steady duopolies and strong incumbent LCCs.

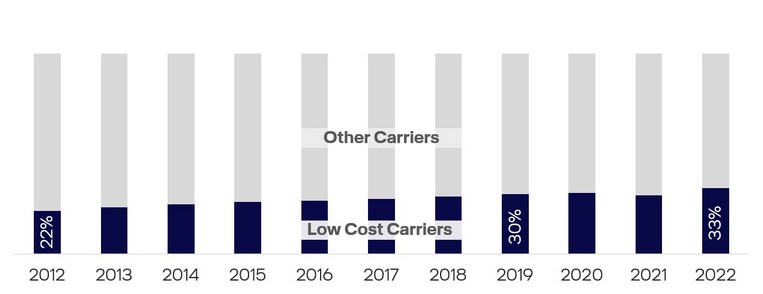

LCCs continue to capture an increasing share of global traffic as low fares stimulate markets and make flying affordable to larger populations than ever before.

Between 2010 and 2020, LCCs represented 19% of passenger airline startups globally, significantly higher than the 9% before 2010. The figure has risen since the start of the pandemic, with 26% of new airline businesses launched since 2020 being LCCs. This is true across both mature markets, such as Avelo Airlines in the US and Bonza in Australia, and in developing markets, such as Akasa in India and Super Air Jet in Indonesia.

Sources: OAG, Lufthansa Consulting

But while resilient financial performances and attractive contribution margins have generated traction for the low-cost (and low-fare) business model, there are several challenges a new LCC might face.

A new entrant is often up against an entrenched incumbent, often government-owned, or other LCCs. Some significant cost elements, such as fuel and infrastructure, may not be entirely controllable by the airline. Further, a competition-driven push for network expansion and low fares also creates significant pressure on operational stability and profit margins. These factors have led many to many LCCs failing.

Furthermore, maintaining sustainable operations after market entry is tough. The difficulty is reflected in the struggles of WOW air, the Icelandic LCC that ceased operations in 2019. Even Norwegian, which was once a case study for LCC expansion, had to shrink significantly to develop a path to profitability.

Our research indicates six business imperatives for a successful LCC:

1. Reliability and good service: For a new market entrant, success often relies on the relevance of its unique selling proposition. Many markets already have LCCs offering lower fare options to passengers, therefore creating the need to offer additional benefits to draw sufficient demand. New LCCs have tackled this in multiple ways, the common factor being a reliable service and a good “value for money” product. Azul in Brazil, for example, maintained a strong focus on offering a very reliable service and differentiating its product from the competition during its initial years. Azul is consistently ranked amongst the most punctual airlines in the world, according to OAG. The airline had an impressive operating profit margin before COVID-19, and CEO John Rodgerson acknowledged the significance of Azul’s punctual operations: “...our success relies on fast and efficient operations … punctuality is so important to us,” he said. Similarly, in India, IndiGo rode its promise of “On time is a beautiful thing” to a dominant position in the domestic market.

2. A common fleet: It is common practice for an LCC to maintain a single aircraft type; a homogeneous fleet allows an operator to optimize the cost of maintenance and training, which can be vital in building an effective cost base. The overwhelming majority of the airlines studied maintained a single fleet type during their early years, typically narrowbodies. In the case of WOW air, the decision to induct widebody Airbus A330s to serve its global ambitions was one of the key factors in the airline’s undoing. That move added significant cost and complexity to a small fleet of narrowbodies.

3. Volume or niche: Building high passenger volumes to leverage scale is a cornerstone of the low-cost business model. Depending on the market dynamics, there are different ways to achieve this. One approach is to go head-to-head with the biggest players on the largest routes in the market and rely on low fares and product offerings to gain market share. VietJet Air commenced operations in 2011 and flew all the major routes in the Vietnam market, facing off against the well-established national carrier, Vietnam Airlines. Within the first year of operations, it was flying on routes that represented about 85% of the domestic market. This strategy allowed it to quickly win a significant share of the market and turn profitable two years into operation. However, such an approach relies on a market with scope for stimulation and a favorable competitive environment. Alternatively, some LCCs have found success in targeting niche routes in highly competitive and mature markets. In France, Volotea focused on stimulating thinner and less-competitive routes when it entered the market in 2012. A majority of its routes during this period had an annual market size in the range of 20,000 to 100,000 passengers. Once it established a presence in the market, Volotea expanded to larger cities such as Paris.

4. Operational scale: The principle of economies of scale is highly relevant in the aviation industry. A larger scale of operations allows an LCC to improve its asset utilization and lower its cost per unit. Depending on the size and competitive dynamics of the local market that a new LCC enters, international operations may be inevitable in achieving the desired operational scale. Air Busan, for example, launched as an LCC focused on the South Korean domestic market in 2007. From 2010, it started international operations to neighboring countries. The expansion allowed it to improve its aircraft utilization (block hours per aircraft per day) by about 10% in a year and further optimize its cost base. The move to international operations was partially necessitated by the relatively small domestic market (approximately 16 million passengers in 2010) and growing competition, with four other LCCs in South Korea in 2010. While expanding operations is critical, discipline in expansion is equally important. Many LCCs have fallen into the trap of expanding a profitable business too quickly. An example of this is German LCC Germania, which increased its operational scale rapidly, especially in the wake of airberlin’s demise in 2017. The aggressive growth strategy coupled with harsh market conditions resulted in the airline declaring insolvency in early 2019.

5. Flexibility: Flexibility and agility in decision-making are critical in the face of stiff competition. Historically, successful LCCs have reacted quickly by reevaluating their strategy, canceling routes and redeploying aircraft. Failure to do so can lead to undesirable levels of cash burn. The Saudi LCC flynas provides an insight into how critical flexibility can be. The airline commenced operations in 2007 with an Embraer-dominated fleet and a focus on offering a no-frills product. However, within five years, it rebranded, established an A320-only fleet and shifted its strategy from being a pure LCC toward a hybrid LCC, which allowed it to better cater to the needs of its domestic and regional customer base. This led to the airline turning profitable for the first time in 2015. Similarly, when Norwegian in its early years faced extreme fare pressure from the incumbent SAS, it was quick to cancel several routes and re-deploy its aircraft smartly, preventing further cash burn and allowing room to build its presence in the market. Norwegian reentered many of these routes later on, capturing much of SAS’s share.

6. A strong financial base: Most markets feature incumbents with deep pockets, meaning many new LCCs face stiff and prolonged price wars. In many cases, the cash burn from strong competition could place a new LCC in a downward spiral with limited means of recovery. However, well-designed market entry strategies that build a war chest and efficiently utilize the capital at hand can allow an LCC the time and space to develop a strong financial footing. For example, Eastar Jet entered the highly competitive South Korean domestic market in 2009 and was instantly involved in prolonged price wars with its competitors, resulting in four financially troublesome years where it racked up significant operational losses. However, the strong financial backing by its investors allowed the airline to fly through its turbulent start. A new LCC with ties to an existing airline group or consortium has a particular advantage. Apart from the financial backing to sustain the heightened market pressure by incumbents, it can leverage cost synergies, such as aircraft or services procurement. Indigo Partners, which owns controlling stakes in several LCCs around the world, including Frontier in the US, JetSmart in Chile, Volaris in Mexico and Wizz Air in Europe, exemplifies this. By placing bulk orders for aircraft, Indigo Partners enables its LCCs to expand their fleet at relatively discounted rates.

There is no silver bullet for success and no single strategy applicable to every LCC launch around the world. Any new airline needs to tailor its approach to the specific market dynamics and competitive context of the market in which it seeks to participate. However, it is valuable for airline managers and investors to learn from past failures and current successes, applying these six business imperatives to maximize the chances of a launch and sustained success.

Arvind Chandrasekhar is an associate partner and Wasiq Khurshid is a consultant at Lufthansa Consulting.