Research Shows The Pointlessness And Cost Of COVID Travel Restrictions

It was the worst public health disaster in a century and the worst economic crash since the Great Depression. And it did the worst damage to the airline industry since World War II. What can be learned from the COVID-19 pandemic that will prevent a repetition, of either the virus or its massive damage?

Every virus is different and methods of dealing with each must be tailored to the virus itself, Sunetra Gupta, a professor of theoretical epidemiology at the Department of Zoology at the University of Oxford, cautions. But Gupta thinks some lessons from COVID can and should be learned.

Jay Bhattacharya, a professor of medicine, economics, and health research policy at Stanford University puts it more strongly. Like Gupta, Bhattacharya warned against lockdowns and all the other restrictions early in the pandemic. He now thinks something similar to an NTSB review of a disastrous aircraft crash is needed to look at how governments mishandled the virus.

Nearly three years after Gupta, Bhattacharya and many others made their arguments, a raft of studies, research reports and meta-analyses of many studies reached the same conclusion: With the exception of fast and tight border closings of a handful of Asia-Pacific islands, all the non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) ordered by governments, including restrictions on air travel, had little effect on virus mortality but imposed massive economic, social, health and other costs on people.

Researchers from the University of Washington and the University of Edinburgh’s Medical School reviewed 600 publications and studies and concluded that lockdowns, school closures, travel restrictions and other NPIs inflicted huge “collateral damage,” beyond that of the virus itself.

During the pandemic, heath visits, diagnostics, therapeutics and hospital admissions declined between 30% and 60% for non-COVID illnesses. Mental health also declined, especially for those vulnerable to mental challenges. Pandemic damage thus included an increase of between 2% and 20% in non-COVID mortality, higher in some countries.

Per capita GDP initially declined about 7% in emerging markets, 5% in advanced economies and 4% in low-income countries. Even after recovery, the 2024 GDP in emerging and developing countries will remain 6% below levels expected before the pandemic, according to the World Bank. Borrowing to counter this slump led to the largest one-year increase in global debt since World War II, which will crimp social expenditures of poor countries well into the future. Income inequality increased both within and between nations. Global poverty increased for the first time in a generation, and 90 million people fell into extreme poverty, receiving less than $2.15 per day as tourism and export demand collapsed. About 350 million people were pushed into food insecurity, risking starvation, according to the UN.

Some of this immense damage was caused by the virus itself or voluntary reactions to the virus. But as much as half the GDP losses were caused by government policies—the NPIs, including travel restrictions—according to economist Douglas Allen of Simon Fraser University, who drew this conclusion after reviewing 100 COVID studies. Yet Allen found that these same policy reactions “had, at best, a marginal effect on the number of COVID-19 deaths.” For different nations, per capita death rates generally showed no relation to the stringency of each country’s NPIs. This was chiefly because people voluntarily changed much of their behavior in light of the virus’s danger to themselves.

Ineffective Travel Restrictions

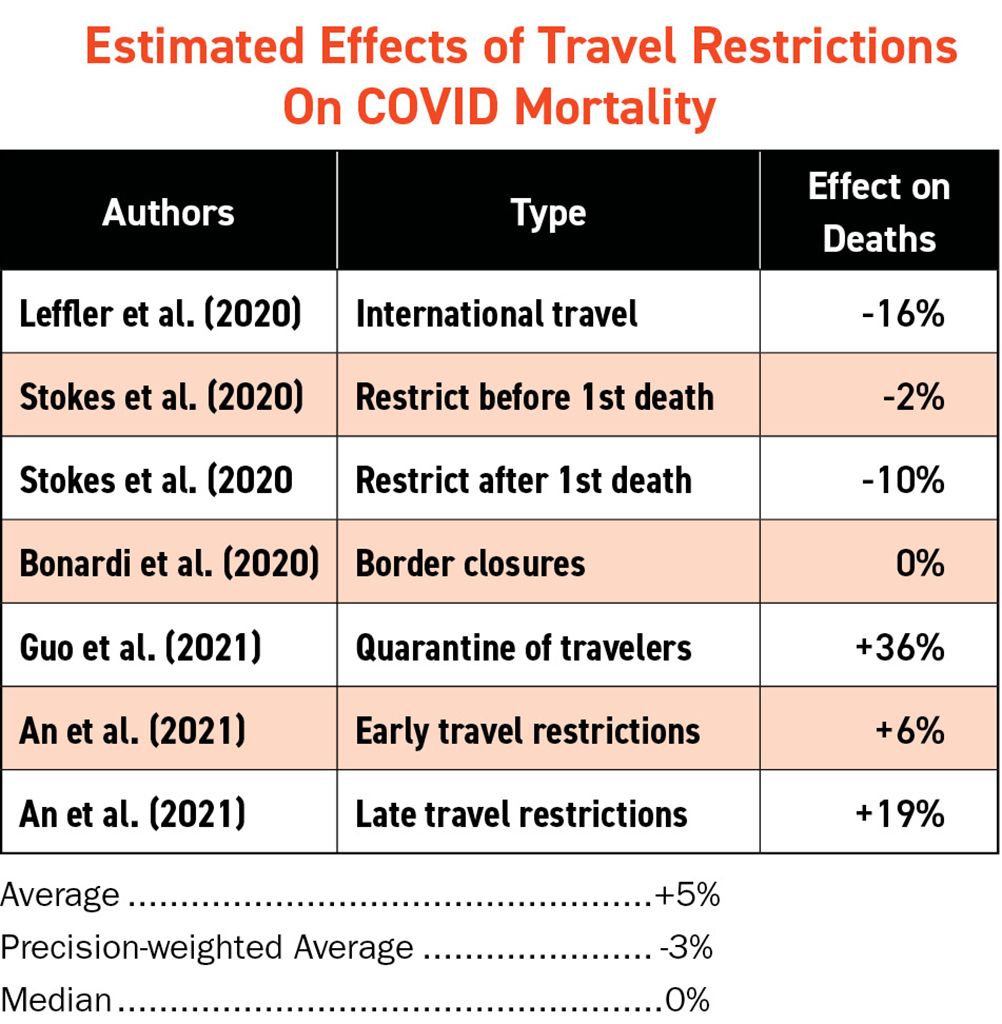

The ineffectiveness of NPIs in general also characterized travel constraints. In May 2022, a survey of five studies of travel restrictions was published by a division of Johns Hopkins University. The best estimate of the authors was an average of study results, weighted by a judgement on the coverage and accuracy of the studies. This “precision-weighted average” estimated that a wide variety of travel restrictions imposed by many countries had reduced COVID deaths by only 3%.

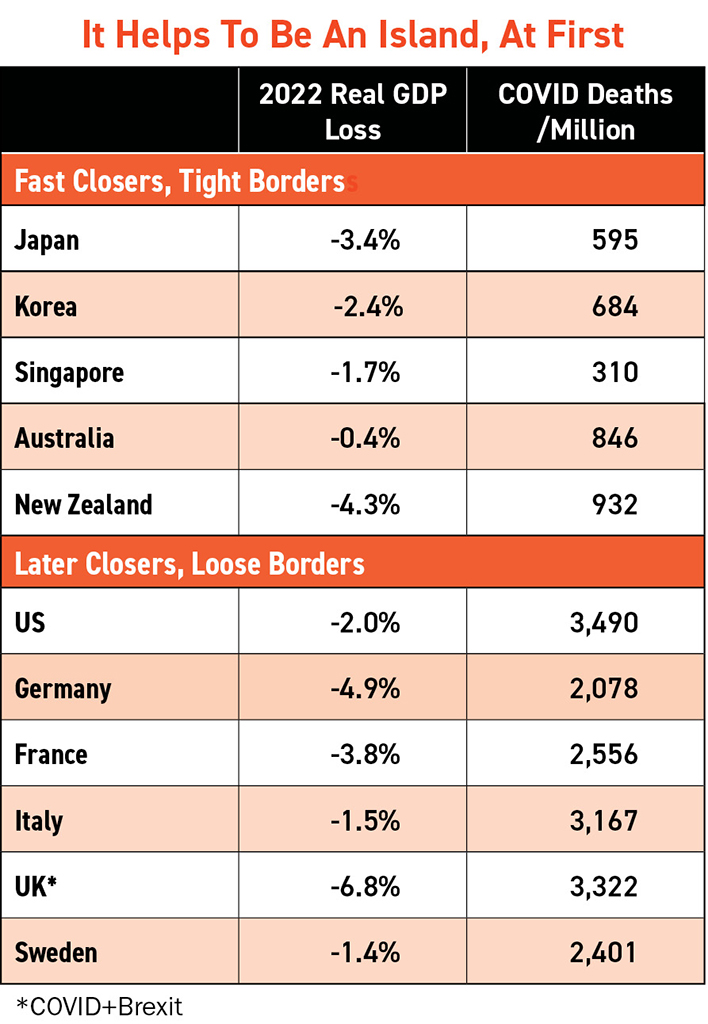

Individual studies differed widely in their estimates. Only one estimated that restricting travel had significant effects. And this study related only fatalities through May 9, 2020, to the speed of border closures, so its estimate is dominated by the early impact of fast closures by Asia-Pacific islands.

A second study found some effects—a 2%-10% reduction in fatalities—but this too focused on short-term impacts very early in the pandemic. Border closures yielded no effects in a third study, and a later study found that travel quarantines were associated with increased deaths. Another later study similarly found travel restrictions associated with increased COVID deaths. In both cases it is likely that higher mortality drove tighter travel restrictions, not the other way around. But neither study shows tighter controls helped.

Taken together, the travel studies provide no evidence that travel restrictions helped much, except for those fast and tight closures in Asia-Pacific.

As the virus mutated, another study explained why the great majority of travel restrictions grew less and less effective as they were prolonged. In January 2022, Oxera and Edge Health delivered a report on the impact of UK travel restrictions on the Omicron variant to the Manchester Airports Group. The report concluded that, “when a variant is already highly prevalent in the domestic environment, travel restrictions are likely to have a very limited impact on the growth and the peak of cases and hospitalizations.”

Omicron had been circulating internationally throughout November 2021, and the UK started requiring pre-departure tests and second-day PCRs in late November and early December. Oxera found these new restrictions had only a mild and temporary effect on preventing Omicron’s spread.

“If no travel restrictions had been in place at all in November/December, cases would have peaked seven days earlier and the peak would have been 8% higher. … Now that Omicron is highly prevalent in the UK, if all travel testing requirements are removed in January, there would be no impact on Omicron case numbers or hospitalizations,” the Oxera report concluded.

In other words, once a virus or variant is established in a country, it makes no or very little difference if a stream of visitors who have about the same proportions of infected, immune and vulnerable individuals as the host population enters the country.

“The horse was already out of the gate,” Gupta notes.

Only in that handful of Asia-Pacific islands (or virtual island South Korea) did snapping the door shut fast and keeping it shut until vaccines were available help at first. But early success led to prolonged and costly slumps in Asian travel, domestic growth and the air connectivity crucial to global economic health.

Shutting down international air travel is only effective in a sudden surge of infections, argues Subhas Menon, director general ar the Association of Asia Pacific Airlines. With COVID, “government response was generally knee-jerk as well as isolationist and parochial, unlike when SARS happened,” Menon said.

A Better Plan

What should have been done about travel and other policy choices?

The World Health Organization (WHO) initially opposed border closures. WHO is now strongly encouraging nations to have already prepared plans in place for dealing with respiratory viruses. ICAO now recommends balancing public health risks with the need for air travel and doing regular risk assessments based on evidence. ICAO says it is essential to maintain air connectivity to support global health, safety, food security, tourism, trade and economic growth. IATA has asked governments to learn from the pandemic and avoid closing borders to manage future health threats.

From the beginning, Gupta, Bhattacharya and many other scientists called for focusing protection on the vulnerable elderly and sick population rather than shutting down society, business, schooling and travel.

“We knew at the outset that COVID vulnerability was highly specific to the condition of individuals—the elderly and frail, diabetes and very obese,” Gupta said.

Gupta ticks off some ways focused protection might be given. Elderly couples living with each other should stay at home, and relatives should be tested before visits. Recovering virus patients should not be placed in nursing homes, but in special facilities. Nursing home staff can be paid extra for working in two-week shifts and should be tested before duties. Elderly persons living with young, healthy individuals might be evacuated to safe facilities during flu season. The Oxford epidemiologist also thinks a pan-coronavirus vaccine should be developed and stored to be offered to vulnerable people if another coronavirus emerges. She acknowledges all these steps would be expensive, but much less so than the lockdown approach.

“The lockdowns did not do a damn thing,” Gupta summarizes. “The whole idea that we could stop it in its tracks was misguided.”

And lockdowns hurt lower-income workers, who could not work at normal workplaces, the most, while leaving the “laptop” class, who could work remotely, relatively unaffected.

Gupta believes something like the COVID respiratory virus might occur again in the next few decades. As for much more lethal viruses like Ebola, these must be contained in a different way, but their very lethality and visibility makes it much easier to block their spread very early.

WHO has urged tighter controls on wet markets, the source of previous respiratory viruses and initially suspected of originating COVID. Johns Hopkins medical professor Marty Makary has urged for a treaty, using principles from a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report, banning laboratories from doing dangerous gain-of-function research.

What all this research adds up to, tragically, is that governments worldwide focused on border shutdowns and travel restrictions that did massive and long-lasting damage to the airline industry and economies but did little to nothing to contain the virus or help their most vulnerable citizens survive. If anything, their policies made them poorer and more vulnerable.

Will those lessons be absorbed and acted upon before the next global humanitarian crisis? Probably not, given how governments have clung to post-9/11 air travel restrictions like the carry-on liquids and gels rules when there are better policies and technologies that could keep air travelers both safe and moving.

The air transport industry, however, should arm itself with the research and data being gathered on the ineffectiveness of government air travel policies through the pandemic and help educate lawmakers and authorities on what they risk if they don’t learn the lessons of the human cost now emerging from the pandemic.