By the 2030s, the B-52s are planned to be equipped with modern turbofan engines and new radar, missiles and communication systems.

Minus tail surfaces, engines and a right wing, the long-retired “Damage Inc. II” B-52 mockup is now installed in the high-bay facility of Boeing’s Oklahoma City engineering center and charged with one more mission: Help keep an $11 billion revamp of the B-52 on track.

Five years have passed since the U.S. Air Force decided to reenlist the venerable Stratofortress for several decades of continued service. With the Northrop Grumman B-21 set under the 2018 Bomber Vector plan to replace the Rockwell International B-1B and Northrop B-2 bombers over the next two decades, the B-52 is planned to keep flying as a long-range, missile-carrying partner to the stealthy, penetrating Raider.

- Physical prototypes are to double-check digital models

- Engineering and manufacturing development phase to start soon

An eight-engine bomber fleet that completed production in 1962, however, requires significant changes to remain relevant until perhaps 2062.

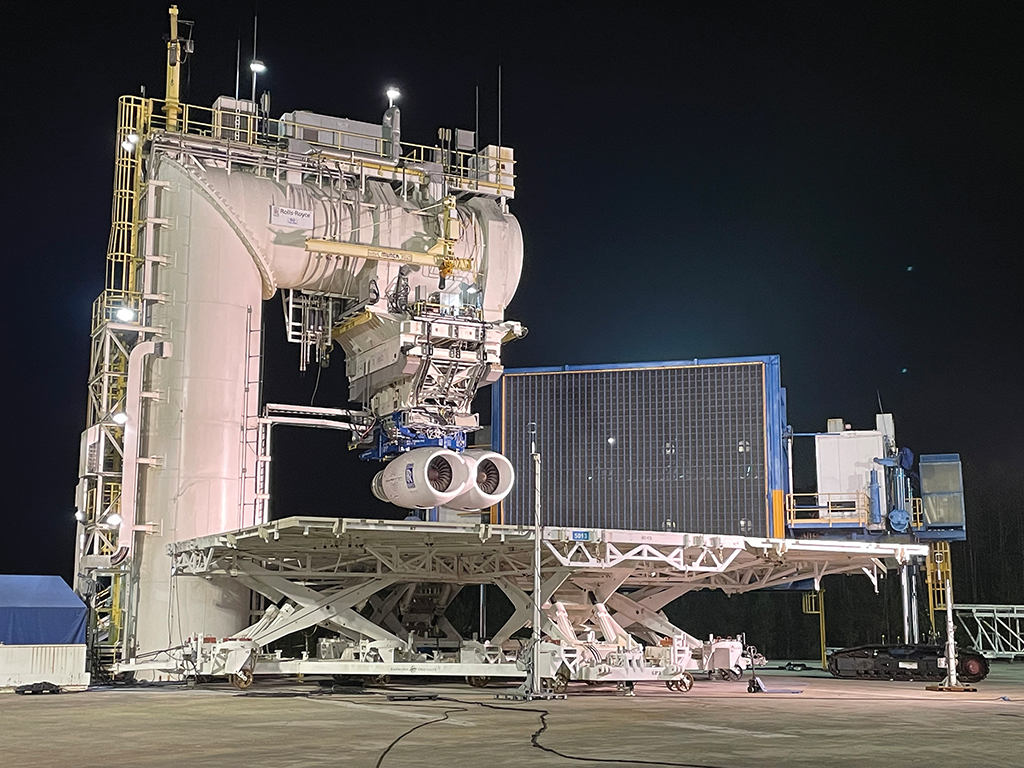

To avoid obsolescence and extend the B-52’s range by more than 20%, the 16,000-lb.-thrust Pratt & Whitney TF33 turbofans are being replaced by BR725-derived Rolls-Royce F130 engines, a modification that requires sweeping changes to internal structures and electronics.

An unreliable mechanically scanned APQ-166 radar, last updated in the 1980s, is being replaced by a modern active, electronically scanned array (AESA), which will allow the B-52 to search the sky, land and sea for threats en route to its missile launch positions.

In combination with other major upgrades, such as the Raytheon AGM-181 Long-Range Standoff missile and new satellite links, the first of 76 redesignated B-52Js should become operational within the next decade. The upgraded fleet will be tasked with lobbing up to 70,000 lb. of long-range missiles at targets from a safe distance hundreds or thousands of miles away.

These multiple, overlapping modernization efforts provoke some anxiety about a fleet with an average age of more than 61 years. Col. Louis Ruscetta, the Air Force’s B-52 senior materiel leader, encounters concerns every time he briefs a senior officer.

“I don’t do a four-star [general] briefing without someone asking the question: ‘Lou, how are you going to do all this?’” Ruscetta told a small group of reporters granted access to the high-bay facility—and Damage Inc. II—on May 17.

On the list of Ruscetta’s responses, Damage Inc. II—a partial B-52H airframe transferred to Oklahoma City last year from the Air Force’s boneyard in Tucson, Arizona—is near the top.

In an age of digital engineering models and virtual prototypes, Damage Inc. II is a throwback, representing a physical test asset to verify that Boeing’s computerized assumptions correspond to reality. For a clean-sheet prototype, a digital prototype is a useful way to verify a 2D design on paper into a 3D model. Since the B-52 already exists, engineers have the luxury of validating a digital model in the real world.

“We still need to recognize that there’s a physical reality to things,” says Jennifer Wong, Boeing’s senior director for bombers.

The placement of an oil can within the nacelle of a right-hand F130 engine may appear accessible in the 3D digital model, for example. But what looks correct on a screen sometimes looks different when an engineer is on a ladder under the wing of a B-52 wearing representative cold weather gear.

Even the physical model of Damage Inc. II has limitations. An aircraft fleet built in the early 1960s and repaired over several decades is subject to a multitude of unrecorded variations beneath the outer skin. To get an idea of the scale of the nonconformances between different B-52s in the fleet today, Boeing engineers selected a sample for inspection. Although fleet-wide design variations have not been mapped out, the company is confident it knows generally what to expect.

Replacing the B-52’s engines is not as simple as removing TF33s and installing F130s. The slightly different dimensions of the Rolls-Royce turbofans change the flutter envelope, so each of the four two-engine pods are mounted higher on new pylons, says Erik LaVasque, Boeing’s B-52 deputy program manager. With the higher position and slightly wider nacelles, more of the exhaust force from the F130 pods is directed at the B-52’s four Fowler flaps. As a result, Boeing is strengthening the flap tracks to support the additional load.

Transitioning from the TF33 to the F130 also changes the electronics in the cockpit. The eight thrust levers are now connected by wires through a series of pulleys directly to the TF33’s mechanical engine controls. Boeing is rewiring the B-52 for the thrust levers to produce a digital signal with an interpretation of the crew’s thrust commands for the F130’s full authority digital engine control (FADEC). The FADECs on each of the eight engines also are designed to send performance updates to newly installed data concentrator units, which would send alerts to the crew if faults were detected.

As the crew is exposed to more system performance data in real time, cockpit displays are being transformed. Two cathode ray tube displays on each side of the cockpit are to be replaced by a single multifunction touch screen.

In addition to a thrust upgrade, the B-52 is receiving a major boost in electrical power. The 45-kVA generators on each TF33 are being replaced with eight 65-kVA generators, increasing onboard power capacity by 44% to a total of 520 kVA. The additional power supply is designed to cover the needs of the new radar, with ample room for growth as the Air Force fields future sensors and weapons, Ruscetta said.

The Radar Modernization Program (RMP) is installing a hybrid Raytheon AESA radar. A modified version of the front-end array from the Boeing F/A-18E/F’s APG-79 is being integrated with a new variant of the radar processor inside the APG-82 on the Boeing F-15E and F-15EX.

“This is probably one of the most critical [B-52 upgrade] programs that we’re doing,” Ruscetta said.

In the absence of stealth or supersonic speed, the survivability rating of the B-52J would be measured by its ability to avoid threats. A payload of long-range weapons is intended to keep the aircraft safely distant from an enemy’s air defense system. If that fails, the radar is intended to make the crew aware of any pop-up threats before the B-52 is within intercept range.

Splicing a modern radar onto a 1950s-era bomber involves deeper changes, however. The radar upgrade comes as the Air Force reduces the B-52 crew to four members from five, with the functions of the defensive system operator transferred to the radar/navigator and navigator stations below the cockpit. Moreover, the Cold War-era sensor displays are to be replaced with two L3Harris Technologies multifunction touch screens measuring 20 X 8 in. on both stations, says Mike Riggs, Boeing’s RMP director. Boeing also is installing two powerful new mission computers to support the new radar.

Ushering each of these overlapping upgrades through the acquisition system has been challenging. The Air Force launched the B-52 Commercial Engine Replacement Program (CERP) in 2019 with a rapid prototyping format, which is allowed by the Pentagon’s Middle Tier of Acquisition authority. But new Air Force leadership decided last year to convert the program into a traditional structure, with an engineering and manufacturing development (EMD) milestone scheduled for this September.

The B-52 CERP remains on track to enter service in 2030, following the RMP upgrade two years earlier. But the schedule could be revisited for the EMD decision, which is to set an acquisition planning baseline required by traditional contracting rules, Ruscetta said.

The Air Force tried to minimize development risk by selecting off-the-shelf hardware, including the Rolls-Royce engine and the Raytheon radar. Those decisions shifted the risk to the structural and electronic changes required to support the F130s, as well as new software code to adapt a fighter radar for the B-52 mission, Ruscetta said.

In addition to the digital and physical prototypes, the Air Force also is expanding test capacity. A normal flight-test fleet of two instrumented B-52Hs has been doubled to support the AGM-181 program. A total of four more B-52Hs are planned to be instrumented for CERP and RMP flight testing, Ruscetta said, with up to two more aircraft available to join flight testing if needed.