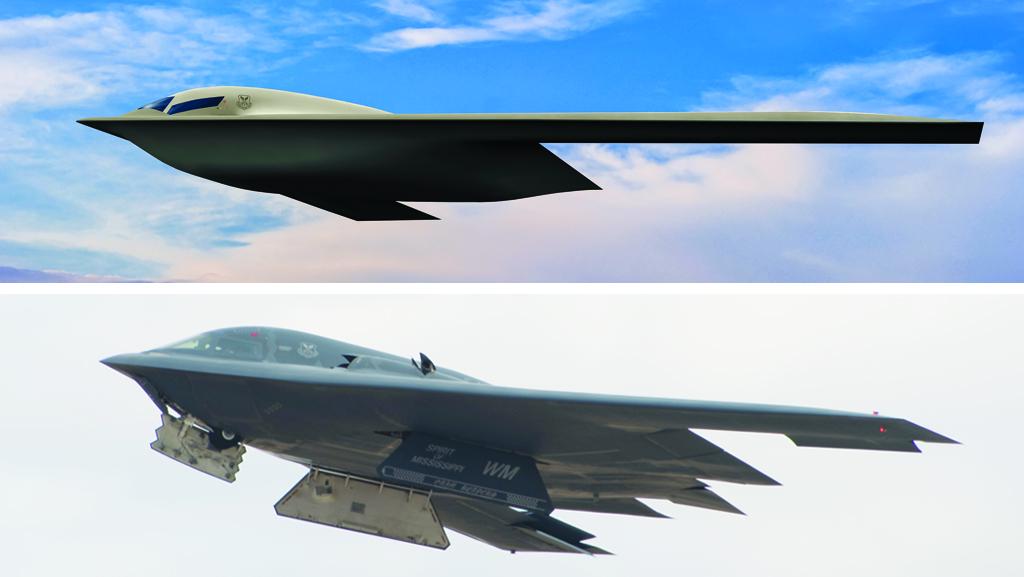

The B-21’s outboard wing sections, inlets and wing trailing edge (top) appear to differ from the B-2 stealth bomber.

Slightly more than 34 years after the rollout of the Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit on Nov. 22, 1988, the U.S. Air Force plans to unveil the B-21 Raider to the public on Dec. 2.

The rollout from the company’s Site 4 complex within the Air Force’s Plant 42 in Palmdale, California, will provide the first glimpse of the physical aircraft since the launch of the Long-Range Strike Bomber (LRS-B) program over a decade ago.

The aircraft revealed during the rollout may seem very familiar, however. While most program information is classified, a perhaps surprising amount of detail about the B-21 Raider’s design, performance and capabilities has entered the public domain since the Pentagon awarded the LRS-B contract to Northrop on Oct. 27, 2015.

- Raider has critical differences from B-2

- Structural optimization of the B-21 is ongoing

The Air Force has released three renderings of the bomber since 2016, showing the aircraft as viewed from above and below on the right side and from a level aspect on the left side. By comparison, the service released only a single rendering of the B-2 before its 1988 rollout, revealing its flying-wing shape and distinctive, sawtooth trailing edge.

Although described as falling short of photographic accuracy, the renderings consistently show a flying-wing bomber resembling the B-2’s familiar design, with certain critical differences.

In comparison to the B-2, the released B-21 renderings appear to reveal:

- Extended, high-aspect-ratio, outboard wing sections compared with the B-2, which may offer improved lift characteristics at high altitude.

- A single W-shaped trailing edge, which appears simplified compared with the double-W, sawtooth shape of the B-2. The latter was added by Northrop late in the B-2’s design phase due to a change in Air Force requirements, which changed to include a low-altitude penetration capability.

- Inboard-canted, wingtop engine inlets. Instead of the B-2’s longitudinally flush, aft-canted inlets, the B-21 appears to deliver airflow to the engines through deeply embedded inboard-canted inlets.

- A three- or four-pane windscreen, including one or two central panes flanked by two upward-sloping, rectangular side windows. By comparison, the B-2 uses four windscreen panels that wrap around the cockpit. Program officials explain that the B-21’s windscreen design will be easier to maintain and should offer better visibility to the pilots during inflight refueling.

- A two-wheel main landing gear. In comparison with the four-wheel bogies on the B-2, the B-21’s half-size gear, if accurately depicted, may indicate a smaller overall aircraft.

Despite these apparent revelations, the renderings leave many other critical details secret. As the Air Force allows the public to view the bomber for the first time, close observers will be on the lookout for confirmation or clues about the following items:

Size Some experts conclude that the B-21 is smaller by at least one-third relative to the weight of the B-2. The Air Force is unlikely to release specifications during the unveiling event, but pictures and descriptions by attendees may help create reliable estimates of the aircraft’s maximum weight, payload capacity and unrefueled range.

Engines The Air Force has confirmed that Pratt & Whitney is the engine supplier for the B-21, but it has not revealed the number or type of engines. The options include two, three or four engines inside each bomber. Pentagon officials approved the B-21 program on the condition that the Air Force use off-the-shelf technology as much as possible.

That may limit the candidates to the Lockheed Martin F-35’s Pratt & Whitney F135 engine or the PW9000, a hybrid engine concept unveiled by Pratt in 2010. The PW9000 integrates the high-pressure core of the commercial PW800 engine and the low-pressure section of the F135. The B-21 entered development more than five years before a new generation of adaptive-cycle turbofans reached the ground-testing stage, which likely rules them out for at least the baseline version of the bomber.

Exhaust system Isaac Newton’s third law of motion attributes jet thrust in one direction to exhausting hot gas in the opposite direction, but combat aircraft operators often prefer not to show that. The aft nozzle of a jet-powered fighter or bomber is usually kept hidden or obscured for as long as possible. An adversary can learn much about the thermal and radar signature of an aircraft from a direct view of the exhaust nozzle. So do not expect to get a clear view of the B-21’s exhaust system.

Subsystems Information about the B-21’s mission systems, including the radar and electronic warfare payloads, has been scant. The only clues are the identities of the eight B-21 suppliers, including Northrop, named by the Air Force. Among the named suppliers are only one radar company (Northrop) and one electronic warfare equipement provider (BAE Systems). Both provide the same systems for the Lockheed Martin F-22 and F-35. If those suppliers are confirmed, it would be consistent with the Defense Department’s policy that the B-21 should leverage existing capabilities rather than take on the risks and costs of developing new subsystems.

Maturity Air Force officials have said the first B-21 flight-test aircraft to roll off Northrop’s assembly line will include missions systems, such as the radar and electronic warfare equipment. By comparison, the F-35 and Lockheed F-22 programs flew flight tests for 3-4 years before integrating such systems. By starting flight testing with mission systems, the Air Force hopes to compress the testing schedule compared with previous stealth aircraft, enabling the B-21 to achieve initial operational capability 9-12 years after contract award rather than the roughly 14-year timeline for both the F-22 and F-35.

Surprises The Air Force has released all three renderings with the caveat that they may intentionally blur, hide or disguise certain features.

Here is a look back at the B-21’s development and what might lie ahead for the new stealth bomber:

How did the B-21 come into existence?

The Air Force’s pursuit of a replacement for the B-2 started immediately after Northrop delivered the last of 21 Spirits nearly 23 years ago.

By the late 1990s, the operational concept for bombers had changed significantly since 1978, the year the Pentagon launched the Advanced Technology Bomber (ATB) program, which led to the B-2A.

The advent of a network-centric approach to warfare required bombers to be far more flexible. Instead of the highly choreographed Vietnam War-era bombing missions against preplanned fixed targets, military leaders wanted a bomber stealthy enough to also loiter in defended airspace and respond in real-time to pop-up, relocatable and mobile threats. Moreover, the military wanted a bomber that could perform such missions in daylight yet still be very difficult for ground-based defenses to detect.

In November 2001, Pete Aldridge, then-undersecretary of defense for acquisition, technology and logistics, signed Program Budget Decision 803. In it, he ordered the Air Force to begin risk-reduction efforts for a new bomber so that the technology would be ready to launch a development program by 2012.

The Air Force, however, resisted his decision. Service leaders had a vision for fielding a hypersonic bomber by 2037 and did not expect the technology to be ready to enter development until at least 2019.

A debate continued for the next four years between Pentagon and Air Force leaders. Starting in 2004, the Air Force proposed a compromise, offering to first field a new version of the F-22 as a Mach 1.8 regional bomber. They suggested that so-called FB-22 replace the Boeing F-15E and Lockheed F-117 fighter-bombers by the late-2010s while work continued on the service’s vision for a hypersonic bomber by the late 2030s.

But Pentagon leaders rejected the Air Force compromise. The 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review again called for the Air Force to field an advanced new bomber by 2018, with flights by a demonstrator aircraft slated to begin in 2011 and contract award between 2012 and 2014. The accelerated timeline ruled out a hypersonic-speed bomber. Instead, the Pentagon launched the subsonic Next-Generation Bomber (NGB) program.

In parallel, the Pentagon also started funding work on hypersonic weapons as an alternative option to bombers for performing the conventional long-range strike mission. DARPA started the air-launched Falcon Hypersonic Technology Vehicle 2 (HTV-2) program, and the Army began developing the Advanced Hypersonic Weapon (AHW).

Both demonstrators were intended to inform the Conventional Prompt Global Strike program. A scaled-down version of the HTV-2 concept has now reached the operational prototyping stage as the Lockheed AGM-183 Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon. The AHW, meanwhile, has evolved into a common system known as the Army’s ground-launched Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon and the surface- and submarine-launched Conventional Prompt Strike missile.

In 2006, the NGB program moved forward on classified risk-reduction activity. Northrop, Boeing and Lockheed Martin entered the competition. Aviation Week reported that the latter two companies received a contract to jointly develop an NGB demonstrator aircraft (AW&ST Dec. 3, 2012, p. 29)

The Congressional Research Service reported in 2009 that the NGB specifications could include an unrefueled combat radius of 3,000 nm and a payload capacity of up to 40,000 lb., which roughly matches the range and capacity of the B-2.

But the program proved unsustainable as ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan sapped budgetary resources. The aggressive schedule, which called for racing to an initial operational capability within six years of contract award, also raised doubts about the Air Force’s ability to execute the contract. Then-Defense Secretary Bob Gates finally canceled the program in the fiscal 2010 budget.

The Air Force quickly revamped the operational concept for the bomber. Instead of a stand-alone B-2 replacement, a new concept unveiled by service officials in 2010 called for a Long-Range Strike (LRS) family of systems. In addition to a scaled-down LRS-B, the family would include a nuclear-warhead-armed cruise missile and penetrating uncrewed aircraft systems (UAS) capable of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance and airborne electronic attack.

The former is now in development as the Raytheon AGM-181 Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) cruise missile. The latter is likely a classified Northrop high-altitude, long-endurance UAS, which Aviation Week has previously identified as the RQ-180 (although its official designation may be different) (AW&ST Dec. 9, 2013, p. 20).

In 2013, Boeing and Lockheed resumed their partnership to compete for the LRS-B contract, uniting the two largest companies in the defense industry against Northrop, the third-largest. On Oct. 27, 2015, the Defense Department announced that the industry underdog, Northrop, had defeated the Boeing-Lockheed team. Nearly three months later, the Government Accountability Office denied a protest filed by Boeing, finding no basis to Boeing’s claims that the Air Force had improperly assessed the costs and technical risks of Northrop’s proposal.

Upon contract award, Pentagon officials said the B-21 was expected to cost $511 million in 2010 dollars, on average, over a 100-aircraft production run. Adjusting for inflation using the deflator index in the Defense Department’s latest Green Book, the average B-21 should cost $623 million, if Northrop delivers 100 aircraft. The Air Force now plans to buy more than 100 B-21s. The exact number has not been released, but service officials say the long-term bomber fleet should consist of 225 aircraft. That number implies a fleet of about 150 B-21s and 75 reengined Boeing B-52s.

Northrop completed the critical design review (CDR) of the B-21 in December 2019. In March 2018, an internal debate over how to size the engine inlets had emerged in public, due to remarks by Rep. Rob Wittman (R-Va.), who was then chairman of the Strategic Forces subcommittee. According to Wittman, Northrop favored limiting the size of the inlets to minimize the impact on the radar cross-section while Pratt & Whitney advocated for larger apertures to increase the mass of airflow to the engine compressor. Air Force officials later said the internal debate had been settled by the time the CDR froze the design, allowing production of the flight-test aircraft to begin.

Air Force officials say the first six B-21s are in various stages of assembly for flight tests, with funding for at least two of the first production aircraft in the fiscal 2023 budget proposal. Northrop also was funded to build six B-2s for flight tests in the 1980s, with all but one being converted to operational bombers after the program completed the developmental stage.

What new threats must the B-21 overcome?

As a second-generation stealth bomber, the Raider became the first aircraft of its kind to enter the design stage since the appearance of an ever-lengthening list of counterstealth technologies, including integrated air defense systems, multistatic radars, infrared search-and-track sensors and possibly space-based systems.

China, in particular, has fielded several counterstealth technologies. In 1998, an Air Force B-2 mistakenly bombed the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade during the NATO air campaign against Serbia. Since that incident, shooting down stealth aircraft has become a key priority in the Chinese military’s “three attacks” strategy, according to Michael Dahm, an analyst at The Mitre Corp.

In August 2020, Dahm, who was then with Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory, published a 28-page analysis of a novel VHF-band radar system erected on the Subi Reef outpost of the People’s Liberation Army in the South China Sea. Chinese researchers have said that this Synthetic Impulse and Aperture Radar (SIAR) overcomes many of the disadvantages of low-frequency radars, including poor angular resolution, unreliable data on the target’s elevation and ground clutter. By using a large circular array with multiple independent transmit-and-receive elements, China Electronics and Technology Group, the manufacturer, says it has achieved significantly improved angular resolution, Dahm wrote.

The Chinese military also has fielded the JY-27A, an active, electronically scanned array radar that operates in the 1-10-m (3.3-33-ft.) wavelength of the VHF band. By using electronic scanning and modern processing, the JY-27A is also designed to improve the accuracy of VHF-band radars markedly in azimuth and elevation.

As a second-generation flying-wing bomber, the B-21 has natural advantages in broadband stealth. A lack of vertical tails reduces the aircraft’s cross-section to radars, especially in lower frequencies such as VHF. Northrop’s designers also appeared to have made several stealth improvements in the shape of the B-21 compared with the B-2. Instead of the flush-mounted serrated inlet edges of the B-2, the B-21’s inboard-canted inlets may provide a reduced signature. The single-W trailing edge also removes two angled surfaces compared with the B-2’s double-W planform. These shaping improvements are likely augmented by a new generation of radar-absorbent materials.

The B-21 faces increasing threats in the optical spectrum, too. Infrared search-and-track sensors are common on modern fighter aircraft. In addition, China has deployed in geostationary Earth orbit satellites such as the Gaofen-4 and Gaofen-13 that are equipped with staring infrared sensors. Although they offer considerably less resolution and are subject to optical challenges such as clouds, these sensors offer a passive alternative to detecting and potentially tracking stealth aircraft by the temperature of their aircraft skin and exhaust gas.

Stealth technology is not a cloaking mechanism. The goal is to make the aircraft hard to detect until it is too late for a defender to act. Even if the aircraft is detected too soon, stealth technology also aims to frustrate radar or optical sensors from establishing a track that is accurate and long enough to guide a missile interceptor.

What comes next for the B-21?

The public unveiling expected on Dec. 2 will allow the Air Force to move forward with a first flight in the next weeks or months from Palmdale, followed by the start of combined development and operational testing by the 420th Flight Test Sqdn. at nearby Edwards AFB, California.

The aircraft to be unveiled will be dedicated to testing but comes close to the production configuration, Northrop CEO Kathy Warden said Nov. 8 at the Baird Global Industrial investor conference in Chicago. The company’s engineers are still working on improving the structural design.

“There are waivers [for the test aircraft],” Warden said. “There are things that are still left to be done in building out the structural integrity of the aicraft to meet the full requirements.”

In 2011, Air Force officials said they wanted the product of the LRS-B competition to achieve initial operational capability between 2024 and 2026. The program’s current baseline remains classified, and the Air Force now describes the date generally as in the “mid-2020s.”

Construction has started at the first main operating base for the B-21 at Ellsworth AFB, South Dakota. Additional squadrons of bombers are planned to be delivered to Dyess AFB, Texas, and Whiteman AFB, Missouri.

Comments