Apprentices wearing BAE’s Striker II helmet in the simulation suite at the company’s Rochester facility.

Complexity is a given in aerospace and defense. It is a condition that applies not just to the industry’s products but also its business operations. BAE Systems’ electronic systems site in Rochester, England, offers a case study.

The facility produces advanced avionics products, including the Striker fighter helmets and the company’s active inceptors, and performs extensive physical and electromagnetic qualification testing. On-site specialization in aircraft optics stretches back to a gunsight for the Spitfire that includes cockpit-mounted, head-up and helmet-mounted display (HMD) systems, each among the leading capabilities of their respective eras.

- Striker II is a baseline for the Tempest pilot-aircraft interface

- U.S. Future Vertical Lift program showing interest in active inceptors

But that history also brings challenges. The site—originally built in the 1930s—needs a comprehensive refresh. Last April, outline planning permission was secured for a multimillion-pound, decade-long redevelopment, so pressure to bring in new business is increasing. And while the company is not yet ready to make an announcement, there are hints that it may be about to secure a first customer for Striker II.

The Rochester team has been carrying out further development of the advanced HMD since launching the system at the Farnborough Airshow in 2014. The product draws on both the Striker I, which is in operation on the Eurofighter Typhoon and Saab Gripen platforms, and work the company did toward a canceled alternative HMD system for the Lockheed Martin F-35.

Since launch, the system has added color to its original green-screen visor display. It also has a video-in-image capability and audio cueing that aids the pilot in assessing a target’s relative position to their platform. Striker II is providing a baseline on which BAE intends to build the pilot-aircraft interface for its Tempest program, but the company cannot afford for the system to be a purely developmental project.

“Obviously, without production contracts, it isn’t sustainable,” says Nigel Kidd, BAE Systems director of head-mounted displays. “I can’t talk on behalf of our customers, but I have a very high level of confidence that situation is changing.”

Kidd says the company has collaborated with the Royal Air Force (RAF) on Striker II’s ongoing development and that 41 Sqdn., the RAF’s Typhoon test and evaluation unit, has flown the system. Feedback from them and other potential end users is being folded into a specification that will go through qualification and enter production. The company expects to be able to announce a customer this year.

“One of the things we can do here, because of what we’ve done on programs all the way back to the basic cueing system on the Jaguar, is [absorb] lots of lessons learned in terms of not just how you design and manufacture, but how the thing gets used and supported,” Kidd adds. “We’ve already taken a number of low-technology-readiness things that we could not put into a product and qualify today and proven them within a Striker architecture. The kind of product we would produce for a sixth-gen platform will look different to Striker, but we are absolutely using all of that knowledge and buildup capability to inform our next product.”

The Rochester site is also able to take technologies developed for military use and repurpose them for civil platforms. The active inceptors the company developed in part for the F-35, which are on Embraer’s KC-390 and Sikorsky’s CH-53K, are part of the Active Parallel Actuator System (APAS) mission system that Boeing has included on the MH-47G Block II Chinooks it is building for the U.S. Army’s Special Operations Aviation Command. The inceptors flew on a Boeing AH-64 Apache in 2015, and BAE is pitching the technology for other upgrade programs. The product was also chosen by Gulfstream for the G500 and G600 business jets, implying a sizable potential market. Addressing that market is challenging, though.

“There’s a lot of interest, both in the commercial world and in some military programs as well,” says Adam Taylor, capability director for the company’s active inceptors business. “Commercial air transport is one application on the commercial side; there’s some military programs, rotary wing in particular because the workload of helicopters is so high.”

In theory, the technology is retrofittable, with the unit containing the stick a straight swap for passive inceptors. But to make full use of the system’s capabilities—which include delivering tactile cues to the pilot through the stick—significant changes to the flight control system would be required, meaning that it is generally adopted during a platform’s design phase.

As a relatively expensive system with nontrivial power requirements, it is unlikely to be of interest to the advanced air mobility sector, ruling out the one part of today’s aerospace business with many new platforms under development. For now, Gulfstream is keeping Rochester’s production lines busy, but new orders would obviously be welcome.

“The U.S. Future Vertical Lift [program] has an interest in the technology, but it’s difficult to work out what’s going to happen because they have competing OEMs,” Taylor says. “But it’s almost like a seesaw, because if all these FVL platforms get built, there’s less money for upgrading legacy aircraft. We’re trying to position ourselves for both.”

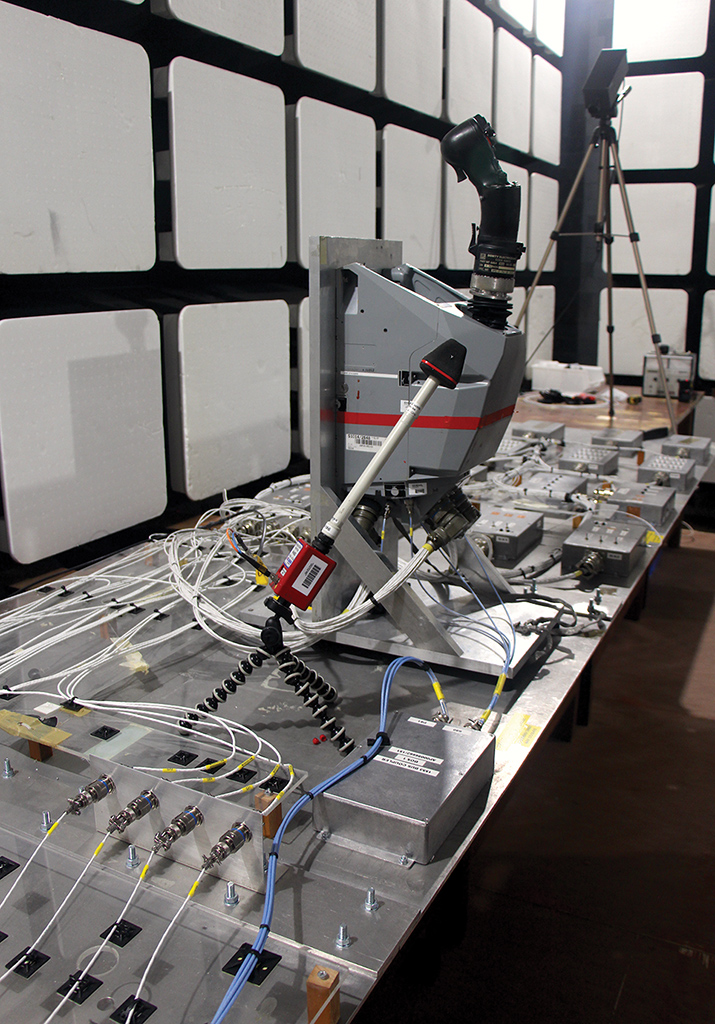

All these programs are aided by the on-site component and system test facility. This is housed in the Faraday Test Center, one of only two buildings on the site—adjacent to Rochester Airport—that will not be demolished during the proposed redevelopment. The center comprises adjacent environmental and electromagnetic compatibility testing facilities, and some of its capabilities—such as explosive decompression testing—are hard to find elsewhere. BAE markets the center to other companies: This not only adds to the bottom line, but aids with recruitment and retention of the specialist skilled staff.

“We test air-data computers, helmets and head-up displays, but also ovens, fridges, microwaves, coffee makers—anything you would need to qualify for use in flight,” says Paul Davison, manager of the center. “It’s a really diverse range of products, which makes it interesting for the guys. They learn the different specs of different products, and they take that knowledge into whichever jobs they do next. It’s a continual learning experience.”