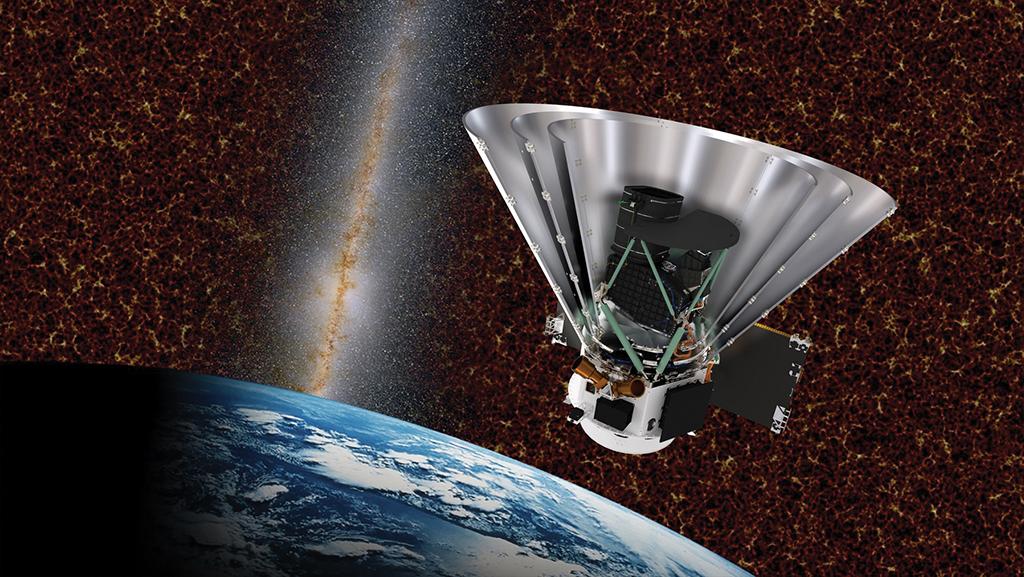

NASA’s SphereX mission is scheduled to launch in June 2024 and fly on a small spacecraft built by Ball Aerospace.

BAE Systems’ $5.55 billion all-cash purchase of Ball’s aerospace unit is the largest acquisition in the UK defense contractor’s history and an ambitious gambit to reestablish itself in space systems after a nearly 30-year hiatus.

Ball Aerospace is a leading supplier of space subsystems to the U.S. government, which accounts for more than 90% of its contracts. Ball had confirmed in June it was selling the aerospace unit, which had become an earnings sideshow for the beverage can giant. The deal was announced Aug. 17.

- The Ball business segment and BAE have strong synergies

- Regulatory opposition due to national security or antitrust reasons is not anticipated

“Space is a growing market, with significant investment being directed into it at both the defense level and the commercial level,” Bank of America analysts Benjamin Heelan and Virginia Montorsi wrote in a note to clients on Aug. 18. Ball’s civil space business could continue to grow, given the steady acceleration of low-Earth-orbit deployments, while “military space is clearly an area of extreme focus in the U.S., which will support growth midterm,” they added.

Ball’s aerospace unit has enjoyed double-digit growth over the past few years: Sales have almost doubled since 2018, and the company’s operating margin exceeds 10%. By BAE’s estimates, Ball’s aerospace business will likely grow about 10% annually for the next five years and could generate $4 billion in annual revenue by 2030.

However, BAE may have “paid a little too much” for the Ball business, Ernest Arvai, president of aviation consultancy AirInsight, tells Aviation Week. With tax benefits, the estimated price drops to about $4.8 billion, a multiple of approximately 15.4 times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (Ebitda). “That’s a pretty good-size multiple,” Arvai notes. “Most [aerospace and defense] deals are 12-14x Ebitda.

“At the same time, the fundamentals for the acquisition are solid,” Arvai continues. “The synergies [between Ball and BAE] are very good. Ball can track anything, including drones, which matches up really well with capabilities BAE has had for a long time.”

Robert Stallard of Vertical Research Partners pointed out in an Aug. 17 note to clients that BAE’s management has said the Ball acquisition does not affect the UK company’s existing capital deployment efforts, including the recently announced $1.5 billion buyback.

“With the acquisition expected to be cash-accretive, this should add to the already healthy coverage that BAE has for its dividend,” he added.

In a conference call announcing the purchase, BAE CEO Charles Woodburn cited “the steady, inexorable shift of priority to the space domain” as a key trend aligning with his company’s strategic direction and customer demand. “Scores of new satellites will orbit the Earth to protect and defend our freedoms around the world,” he said, adding that the proposed acquisition would boost BAE’s space footprint, extend complementary customer relationships in national security and provide new access to civil space markets.

Acquiring Ball’s aerospace unit could also strengthen BAE’s capability to counter hypersonic weapons, an area in which the U.S. is competing intensely with China and Russia. Ball is partnering with Northrop Grumman to develop two mission payloads for the U.S. Space Force that will be equipped with infrared sensors to detect and track both ballistic and hypersonic missiles.

From a regulatory standpoint, there are no red flags. Several UK-U.S. aerospace and defense deals have occurred in recent years. The two countries share a rare defense trade cooperation treaty, and BAE Systems has long worked closely with the Pentagon.

“BAE and the UK are part of an extended family” of the U.S.’ partners, Byron Callan, managing director at Capital Alpha Partners, tells Aviation Week. “This company is working on the electronic warfare system for the [Northrop Grumman] B-21 stealth bomber, which is kind of a keys-to-the-kingdom program.” With that level of trust, it is unlikely that the acquisition of Ball’s aerospace unit—through BAE’s separately run U.S. subsidiary—will run into regulatory opposition, he says.

From an antitrust angle, the deal would not lead to any obvious vertical integration that regulators would find concerning. “BAE is already a merchant supplier in many ways,” Callan says. He notes that while Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.)—a consistent critic of defense sector consolidation—may object to the deal, a press release from her office “is not something that should be read to indicate a new policy shift.”

Pointing out that the onus will be on BAE to integrate Ball Aerospace well, Callan says: “Can you cross-pollinate the businesses? If you can, you can have a real winner on your hands.”