MRO Market Changes And Trends To Expect In Pandemic Recovery

As more of the population becomes vaccinated against COVID-19 and domestic airline traffic picks up, there are increasing signs of hope for an air transport sector recovery—although most likely it will take at least another year or two to complete. Following are answers to some important questions about the path forward from Aviation Week editors who cover maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO), commercial aviation and business aviation.

- Airlines and MROs accelerate digital initiatives

- Expect robust M&A in the aftermarket

- Demand for used material is increasing

What is the status of the global fleet, and what is happening with all of the parked aircraft?

Aviation Week Fleet Discovery data show that 22,287 civil aircraft—-including narrowbodies, widebodies, regional jets and turboprops—are in service. In addition, 2,188 are in parked/reserved status, 3,400 are parked, and more than 6,000 are stored.

It is important to distinguish between parked and stored aircraft for maintenance purposes. Airlines select the short- or long-term options based on their fleet plans, business models and how long they think aircraft will be on the ground. Parked/reserved aircraft typically fly a few days over a seven-day period—so they are poised to quickly return. Both parked/reserved and parked aircraft require maintenance at regular intervals, and engines need to be run and systems checks performed before reactivation. Aircraft in approved maintenance storage programs require engine preservation (covering or removal) and disconnection of major systems, regular inspections and servicing during storage, as well as “full functional checks of all critical components before returning to service,” says Ascent Aviation Services. It is storing more than 400 aircraft at its locations in Marana and Tucson, Arizona.

Claire Kauffmann, head of scheduled maintenance services for Airbus, says stored aircraft require a few days to a week of maintenance before reactivation, depending on the MRO performing the work and whether the aircraft are narrowbody or widebody.

“We did see some cases of bird-nesting, some cabin damage in high-humidity areas or battery depletions. These were always related to some of the prevention measures either not [being] done or not fully implemented due to various reasons,” says Kauffmann. Airbus emphasized the preventative measures that were needed and sometimes provided alternate solutions, she notes. For instance, early in the pandemic last year, there was a worldwide shortage of engine covers, so Airbus provided other options as well as 3D drawings to operators who could manufacture their own.

While parking and storing aircraft are not new, the scope and immediacy of what was required last year was unprecedented. Some lessons have been learned.

For example, Boeing started providing methods to reduce aircraft humidity to preserve line-replaceable units (LRU) such as batteries, soft interiors and auxiliary power units, and making sure the “LRUs are maintained in extreme weather conditions (below freezing and over 110F),” the OEM says.

Boeing also has worked with its suppliers “to publish the latest preservation information provided to us for various components in our maintenance manuals,” it says. As technical issues have arisen, it has issued temporary revisions of the manuals to proactively ensure aircraft safety.

While the industry is flexing to keep up with changing requirements, “the biggest issue for us so far has been the ever-changing schedules from our airline partners, mainly due to changing load factors, 737 MAX jets reentering service and grounding of other fleet types,” says AerSale, which has about 500 aircraft parked or stored at its facilities in Goodyear, Arizona, and Roswell, New Mexico.

One interesting note: Aviation Week Fleet Discovery data show that 677 commercial jet and turboprop aircraft were retired in 2020, almost exactly the number—680—that were retired in 2019.

When will retirements begin to affect the used/surplus parts market?

This already is happening, albeit perhaps not as quickly as some expected, given the scale and duration of the groundings. But groundings and stored aircraft are not the same as retirements. Retirements are what drive used serviceable material (USM) and the offloading of parts that are no longer needed to support fleets. Many operators are taking a wait-and-see position before they remove aircraft from their books, lest they be caught without enough lift to support a sudden bounce-back in demand.

“There is a lag, of course, from the time a plane is retired to the time that we would see it in the USM market,” General Electric CEO Larry Culp says. “But as we look out over the next several years . . . we [will begin to] see a return to normal-volume activities.”

Retirements are just one of the keys to a vibrant USM market. The other is aftermarket demand to support the active fleet. That is tied to flight activity and demand for air travel.

Most in the industry believe the return to 2019 activity levels will come around 2023 for the narrowbody fleet and perhaps a year or so later for widebodies. There will be exceptions within each segment, but the fleet workhorses—Boeing 737s, Airbus A320s and their engine types, for instance—are likely to be at the leading edge.

While it will take some time for aftermarket activity to reach 2019 levels, there are clear signs that the recovery is underway as operators prepare for an expected surge in demand, particularly for leisure travel. AAR Corp. reported a sequential increase in hangar-space demand for the three months ending Feb. 28 and says it sees “increased interest” in USM demand for current-generation A320s and 737NGs—a solid leading indicator of market recovery.

How will technology and data strategies develop post-crisis?

The current state of the commercial aftermarket’s digital landscape paints a mixed picture. While pre-crisis plans for technology adoption and tapping into big data analytics have not changed radically as a result of the crisis, cutbacks are being made, particularly by airlines looking to preserve cash. Last year, carriers reduced IT spending to $20 billion, compared to the $50 billion spent in 2019, according to SITA’s 2020 Air Transport IT Insights.

Despite these financial constraints, digital adoption by airlines still is happening and likely will progress, with some carriers turning toward digital platforms to improve functions such as maintenance planning and fleet management. Lufthansa Technik noted strong customer demand for its Aviatar platform in 2020. United Airlines now has 600 aircraft covered by Aviatar: Last year it added digital support for its Boeing 777 fleet to the A320s already covered by the platform. Other carriers upgrading technology for the post-crisis future include Sri Lankan Airlines, which is looking into using big data analytics for predictive maintenance, as well as 3D printing, enhanced inspection methods and robotic auto-mation systems.

MRO providers with sufficient capital are aiming to invest in digital solutions, but some companies are revising these plans in view of how the aviation industry landscape has changed over the past 12 months. “Even though we have not slowed down in our technology investments, it has definitively made us revise our plans to make sure that our initiatives are aligned with the changes that the aerospace markets have experienced,” says Alejandro Mayoral, senior vice president for information technology at StandardAero. “Additional supply of usable serviceable material, changes in MRO workscopes, demand variability—they all drive the decision on what digitization programs to focus on first.”

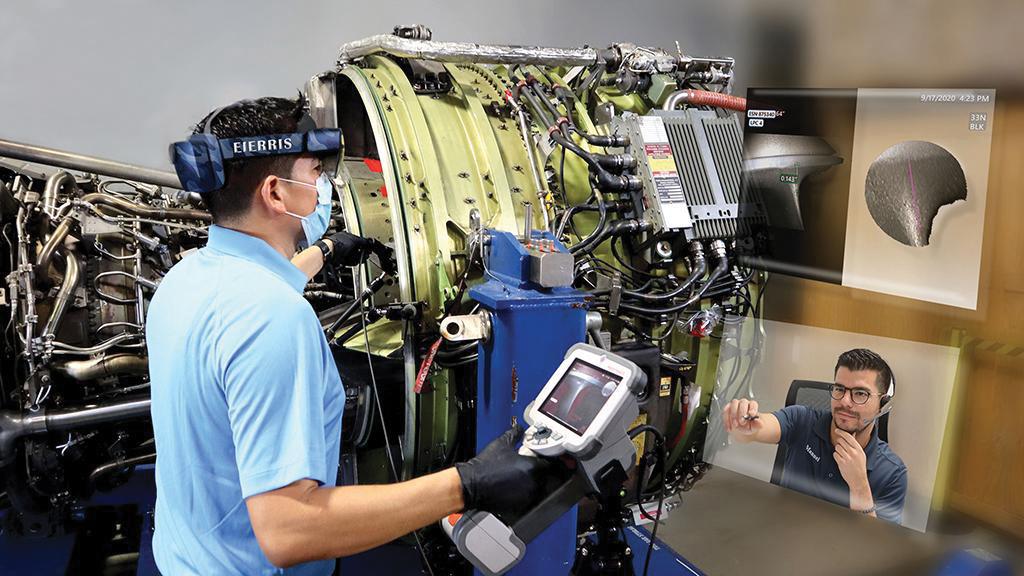

Nevertheless, the changes brought about by COVID-19 have presented a good opportunity for some companies to innovate. The emergence of remote digital inspections, particularly for engine and component maintenance, is anticipated to remain a fixture for the near term, at least with cross---border travel restrictions still in place in many parts of the world. Over the past year, these inspections also have been extended to the regulatory side of some businesses. U.S.-based AAR has turned to augmented reality to enable regulators to conduct socially distanced site visits.

“With remote working and social distancing becoming commonplace, remote-assistance technology is ready and available and has been taken up by more and more businesses who are quick to see the benefits and adopt the solution,” says Mike Egan, vice president of commercial aviation at global technology provider IFS. Egan adds that generally the Asia-Pacific region is leading the charge on digitization efforts, but he says digital adoption cannot be determined only by regional trends. “The ability to lean forward during this period is somewhat dependent on the state of the business pre-pandemic and the level of government support received during the crisis, so this is not completely regionally based,” he says.

In China, Gameco is tapping into new technologies at its Guangzhou base. Its future priorities, according to CEO Nobert Marx, include “building the Internet of Things by using [radio--frequency identification (RFID)]; digital monitoring technology; further realizing the digitization of tools, aviation materials and equipment; and obtaining tracking and status data in real-time.” Marx adds that Gameco also plans to build a new maintenance production system that will meet the needs of a digital operation based on both mobile and Internet of Things technology.

Despite financial hits to their orderbooks and potential readjustments of their aftermarket strategies, OEMs remain keen to grow their marketshares through their own data offerings. Boeing, which launched its data analytics platform in 2019, has seen robust demand for digital services. Airbus has continued to expand its Skywise data platform, which has more than 130 airline customers. Last summer, it developed several offerings including an application to help airlines decide where to store ground-ed aircraft.

A further expansion of offerings is anticipated from digital service providers catering to a changing industry. This may develop at pace across the MRO supply chain, which likely will rely more heavily on digital applications post-crisis as a means of minimizing risk in the event of another global disruption. Greater functionality is expected to be added across digital supply chain tools as the segment seeks to become better connected across multiple entities.

How is M&A trending in MRO?

Mergers and acquisitions are expected to be generally more active in MRO and the aftermarket than in most other aerospace and defense (A&D) subsectors. Several deal-makers and consultants see M&A activity in companies focused on government services leading now, while activity in the commercial aftermarket should increase as the year progresses. Defense industry M&A has kept pace. But consolidation in the OEM supply chain is expected to lag for most of the year and may not pick up until 2022.

Bill Alderman of his eponymous A&D middle-market investment bank told PNAA’s Annual Aerospace Conference this year that he anticipates an active M&A market in the aftermarket supply chain.

But he sees limited M&A activity until at least later this year due to depressed values and unmotivated sellers—no one wants to sell at 2020 prices—as well as the flood of buyers attracted by potentially distressed assets. “There are a lot of buyers out there—especially in the financial side of the market—looking to buy into the commercial aviation supply chain. However, there are not that many sellers because valuations are depressed, and there has been ample liquidity—Paycheck Protection Programs 1 and 2—and banks are not foreclosing,” he says.

While prospects in different corners of A&D and government services appear mixed, deal-makers universally report ongoing intense levels of overall activity. “We haven’t seen any let-up,” says Bob Kipps, managing director at KippsDeSanto. “I’ve been doing this a long time, 25 years, and this is the best market I’ve ever experienced.”

In a way, “everyone is a seller,” especially smaller companies, Kipps says. “The buyer universe is deeper and broader than I’ve ever seen.”

Beyond strategic corporate and traditional private equity investors are family offices and a myriad of others dipping their toes in the A&D and government contracting markets.

What is motivating the M&A surge?

Recoveries from historic lows always promise one thing—growth—and those who want to focus on MRO and the aftermarket are expected to double down, with a few major exceptions. For instance, Triumph Group announced in February that it had struck a deal to sell its Red Oak, Texas, operations to aerospace private equity investors Arlington Capital Partners. The agreement marks the second-to-last disposal of major aerostructures-related assets under a multiyear restructuring by the Tier 2 supplier as it focuses on engineering and MRO services.

Surprisingly, one pre-pandemic heavyweight not expected to make major M&A moves in MRO is Boeing. Several aerospace consultants have said in recent months that the company’s pre-COVID-19 goal of deriving $50 billion in annual revenue from Boeing Global Services has been all but abandoned. While Boeing’s leaders have not confirmed this, they also have not said much about the aftermarket division.

But with net debt of $38 billion, more than 500 undelivered 737s (including those at Spirit AeroSystems) and 787s, a looming decision about pursuing a midmarket airliner competitor to Airbus that could cost $15-20 billion and relationships to repair around the world—including with suppliers—Boeing’s pre-pandemic vertical integration and aftermarket efforts are expected to remain on hold.

What new trends will emerge in aftermarket M&A?

In March, Oliver Wyman consultants reported that M&A trends expected to emerge after the pandemic include the growing role of “new money”—that is, private equity, family office and other relatively new outside investors.

Jerome Bouchard of Oliver Wyman says new investors will serve multiple purposes. “Of course there is the pure financial appetite of buying low and selling higher when the recovery finally comes,” he says. “But some of them also are here to play a consolidation role.”

Dennis Santare, also at Oliver Wyman, agrees and sees the outsiders as taking advantage of the industry’s historic resetting. “New capital is going to win versus old,” he says. “The new capital is going to come in and take advantage of a much better business case, much lower valuations.”

Another M&A trend to watch will be the significant—albeit undetermined—effect of the expected used serviceable material (USM) surge from aircraft retirements. “Do USM companies need that capital injection . . . to buy those [feedstock] assets? We see quite a lot of interest in the [private equity] market in the USM market to help those USM providers be agile, to buy the assets and to buy well and sell well,” says Oliver Wyman’s David Stewart.

What is the state of the MRO workforce as the industry recovers?

Aviation Week’s 2020 Workforce Study found that by mid-2020, close to 115,000 jobs in aviation had been wiped out due to the downturn. Layoffs and furloughs affected many areas of the aftermarket, and more experienced mechanics chose to retire early, which accelerated the projected workforce shortage. According to Boeing’s 2020-39 Pilot and Technician Outlook, the industry will need close to 740,000 new maintenance technicians through 2038.

Boeing’s outlook also predicts that some furloughed personnel will find employment in the government, business and general aviation sectors, which previously struggled to compete with commercial demand. Aviation maintenance technician (AMT) schools, MRO providers and staffing agencies have reported this to be the case over the last year. Mike Guagenti, CEO of Launch Technical Workforce Solutions, says the market was tight during the pandemic, and areas such as business aviation, cargo and aircraft storage have scooped up available workers in greater numbers.

“The talent that moved into those markets has really been there for more than a year, and until these fleets come out of the desert, there’s still going to be a pull into those areas,” says Guagenti. “Those MROs and the operators that focus on cargo were able to add talent during the peak of the pandemic. Now, [that is] being compounded by the fact that the airlines are adding more capacity to their fleet schedules. Trying to reload talent is putting a lot of pressure on the market.”

How will MRO meet workforce demand as aircraft come back into service and commercial traffic increases?

MRO providers that had to furlough staff and close facilities, such as AAR, now report hiring back all the talent they could, but some technicians have left the industry for greener pastures. “We are a little smaller than we were pre-pandemic, because we called some people back who had gone to other industries,” says Brian Sartain, AAR’s senior vice president of repair and engineering services, citing the package-shipping and trucking industries as two areas that drew away MRO workers.

However, industry initiatives could help draw skilled technicians back into the fold. Many MROs and airlines never stopped programs to recruit military veterans and next-generation talent into the workforce during the pandemic, and these programs are ramping up as demand continues to grow. The FAA also began accepting applications for the Aviation Maintenance Technical Workforce Grant Program in January, which makes a wide range of workforce development activities eligible for grants of $25,000-500,000.

How has the pandemic changed the regulatory landscape?

MRO oversight may be one of the few areas that has benefited from the global pandemic. Regulators realized early on that they needed to adapt quickly in order to continue doing their work. Simple tasks such as sending teams of inspectors to repair stations suddenly became logistical nightmares due to travel restrictions. Many regulators adopted new ways of working, such as using remote technology like video feeds in lieu of having an inspector on site.

The FAA has relied on virtual collaboration during the pandemic to conduct the Boeing 737 MAX evaluation as well as a technical advisory board’s evaluation of some Boeing 777X certification issues. By all accounts, the pandemic’s limitations did not delay these critical projects, underscoring that often-rigid regulators can evolve quickly if needed.

The good news is that such new approaches are likely to remain after the COVID-19 crisis is over.