KLM Engineering & Maintenance has partnered with startup Mainblades to apply its drone inspection technology to the paint peeling issue that has long plagued operators of Boeing 787 and Airbus A350 aircraft.

The issue has been attributed to several causes, including ultraviolet ray damage, thermal cycling on composite materials and “rivet rash,” where paint does not stick well to titanium fasteners. Although the issue appears to be mainly cosmetic, it is not a particularly good look for operators when passengers see what appears to be duct tape on the wings—the high-speed tape that is applied to temporarily mitigate the peeling.

The issue could also pose a safety threat to technicians during manual inspections of the damage or applications of high-speed tape. The FAA released a Safety Alert for Operators (SAFO 20006) on April 6, 2020, warning that 11 Boeing 787 operators had reported failures of vacuum-based fall-arrest protection systems due to paint lifting off and away from the surface of the aircraft’s upper wing skin.

Drones have long been trialed as a way to make visual inspections of aircraft more accurate and efficient, and in light of the FAA SAFO, it is unsurprising that some operators are now seeking an automated solution to tracking this type of paint damage.

According to Mainblades, KLM Engineering & Maintenance approached it with the idea of using drone-based inspections to get a better, more consistent overview of how much tape was currently applied to an aircraft wing and to predict when repainting was needed.

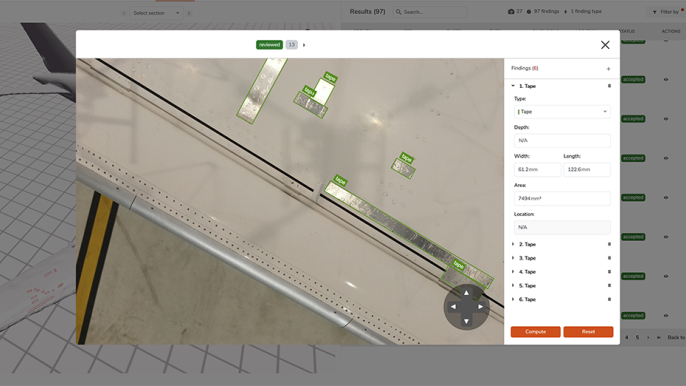

Credit: Mainblades

Dejan Borota, co-founder and CEO of Mainblades, says KLM received guidance from Boeing to perform paint peeling checks every eight weeks—essentially, during every A check. However, based on KLM’s maintenance schedule, each aircraft was in for maintenance at least once a week to perform smaller maintenance tasks, so the airline sought to perform these types of inspections during this period.

“They have this R check, which is like very week or every second week for an aircraft, and we can do an inspection in 20 minutes,” says Borota. “It gives them so much more information about this issue and the progress, because they want to see how much tape they apply and how much paint is peeling. So instead of having one data point for two months, they actually get one data point—or one measurement point—per week, in a fraction of the time at no cost, because we do these inspections now for them while they’re doing other [maintenance].”

Borota says Mainblades’ software automatically identifies and labels both paint damage and tape using high-resolution images and measurements, so it can predict where damage is occurring, where tape will be needed next and how much the damage is progressing. He says these drone inspections are significantly quicker than manual inspections, which take KLM approximately three hours. Manual inspections also require a technician to climb up on the wing, which could potentially present a safety issue in light of the FAA SAFO.

Mainblades has already performed around 40 paint peeling-related inspection flights and Borota says the use case is still in the development phase under KLM’s Part 145 license. The next step will be for KLM to present the results to regulatory authorities and Boeing as an option that is equal or better than manual methods. He hopes that Mainblades will eventually be able to offer the service as part of its service package.

“It’s so obvious it’s so much better because you don’t have to get an engineer up there. You don’t have to do an inspection only once every two months—you can do it every week,” says Borota. “We hope that from next quarter this will be standard operating procedure for KLM engineers.”