U.S. Air Force Looks To A Future Of New Tech For Same Core Missions

Throughout its 75-year history, the U.S. Air Force has evolved how it employs airpower through decades of technological advancement, though its core missions have largely stayed the same.

Going forward, these are likely to remain as currently defined: providing air and space superiority; intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR); rapid global mobility; global strike; and command and control. However, the service is planning for broad changes in how each is addressed, at a time when key technologies have evolved to where they may be deployed sooner than many think.

- Plans for autonomy beyond the NGAD’s loyal wingman

- Moving-target engagement to be an air and space mix

- Core missions will likely stay the same

At the Air Force Futures office at the Pentagon, this planning is based on extensive wargaming, analysis in cooperation with industry and joint planning with other services. The head of the office, Lt. Gen. Clint Hinote, deputy chief of staff for strategy, integration and requirements, points to two key areas as examples of where the service is headed: increased autonomy and the further migration of missions, and weapons, to space.

“The core missions of the United States Air Force have never really changed. In fact, if you go back to our founding document, in the National Security Act, [they] haven’t changed, and I don’t think [they] are going to change very much,” Hinote says. “But of course, how we do them changes significantly, depending on the technology we have.”

The Rise of Autonomy

While the rise of remotely piloted aircraft has revolutionized the Air Force, especially in how it conducts airstrikes and surveillance in passive environments, the service is looking to quickly move ahead in flying more advanced missions with highly capable uncrewed aircraft, and on a shorter timeline than some expect.

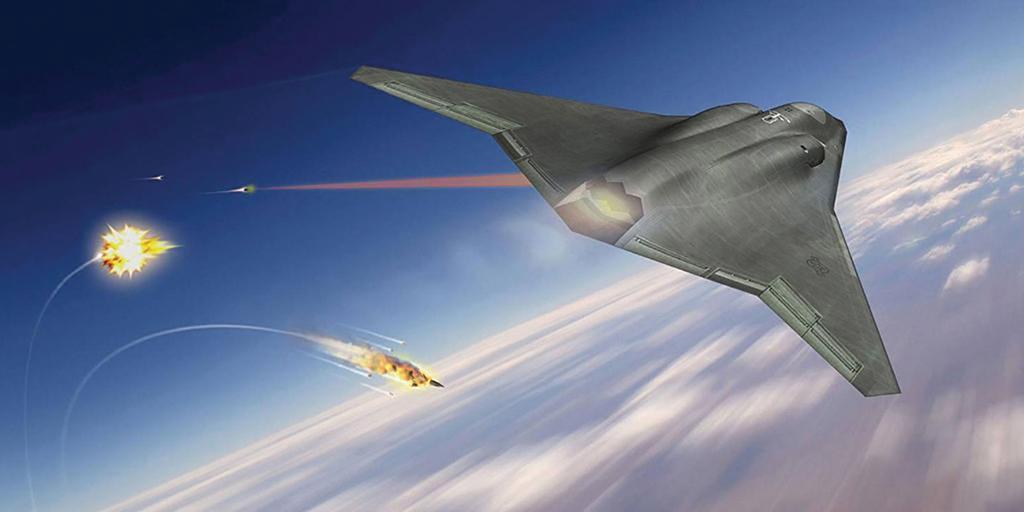

Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall has made the development of a Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA)—an uncrewed, highly capable drone to fly with a sixth-generation Next--Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) platform—a top priority, with his road map expected to be laid out in the service’s upcoming budget plan, to be released next spring. Hinote says the work on the CCA has shown that the technology could be ready in the next 5-10 years. “It has the potential to really change a lot of the indicators that we have that are red to green,” he says.

The CCA builds on technology developed in programs such as the Air Force Research Laboratory’s (AFRL) Skyborg and Boeing’s Ghost Bat, and in the last few years it has matured “incredibly rapidly,” he says. This has moved beyond the major players—Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman and others—and into smaller focused companies that can contribute advanced software development, especially spurred by outreach under new programs such as the service’s AFWerx innovation incubator.

“We’re also seeing a significant amount of newer companies, or certainly newer in the industry, coming to the fore and offering parts of the puzzle, and we’re really excited about both of those,” Hinote says. “We need a wide range of industry in this. I am optimistic about the timelines. I actually think the timelines can happen faster than many people have projected. Why do I say that? Because I’ve seen that the autonomous part of the system is really making progress very fast.”

The AFRL’s Skyborg has shown that the autonomous brains of the aircraft can operate in a rudimentary fashion and be used on multiple platforms—this will be a building block on the way to more advanced loyal wingman-type aircraft. In the beginning, the Air Force does not need “the most exquisite levels of autonomy,” Hinote says. It can be simple. Complexity can come later as the technology evolves.

“They don’t necessarily have to be able to dogfight in an effective way. These aircraft do need to be able to avoid the good guys and be able to find the bad guys,” Hinote says. “But generally, what we’re seeing is that this type of technology we’ve pretty much got.”

The tactical combat aircraft will not be the only use for this type of autonomy, as it can be adopted for the other core missions. The Air Force is wargaming out how autonomous aircraft could perform mobility, personnel recovery, strategic bombing, intelligence among other missions, and in what sequence.

“What’s the most compelling use case right now, with the given state of the technology? How do you field those? How do you really get those in the hands of the airmen so that they can field the capabilities?” he asks. “And we’re right now trying to figure out what the right sequence of these mission sets is: Do you do ISR before you do strike? Do you do some sort of rapid, last-tactical-mile logistics before you do something that feels like a bomber? All of those things are things that we’re wargaming out, analyzing right now.”

A major hurdle on the road to autonomy is not necessarily the maturation of the technology but how the human in the loop can interact with the autonomous aircraft. This is critical for a Collaborative Combat Aircraft—one that would fly as a bomb truck, an additional sensor or a decoy alongside a crewed NGAD. How can a pilot establish trust with that drone?

From the earliest days of airpower, U.S. Air Force airmen have “led the way” in building trust in technology, Hinote says. This goes back to strapping in to the first supersonic aircraft on test flights.

“We are going to have to do it again,” he says. There are ways the service can build that trust. The Air Force is extensively looking at using uncrewed combat aircraft as adversaries in training. Through exercises, pilots can fly against these new aircraft as they would against a red air F-16 during a Red Flag exercise, and build an understanding of their capabilities and how they work.

There is also a flip side, one that will be critical to how the Air Force can operate with autonomous systems. “Here’s what I think is the most fascinating part: At the same time [that] we need a high level of trust, we also need to have a healthy level of distrust,” Hinote says.

A capable opponent in war will do everything it can to undermine U.S. combat capability, and this would include cyberattacks to manipulate a database or the algorithms that the uncrewed aircraft use. The Air Force knows this because it expects to do the same thing. Its pilots would need to be ready.

“There is a very interesting dichotomy of trust and mistrust that tomorrow’s airmen [will] have to have,” Hinote says. “They [will] have to trust the machines to be able to get the most out of them in combat conditions, but they also [will] have to have enough distrust to know when the machines aren’t doing what they should be doing. . . . I don’t know how to do that quite yet, except that we’re all going to have to learn about the limits of this autonomy [and] the limits of artificial intelligence altogether.”

A Space and Air Force

In 1996, then-Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Ronald Fogleman and Air Force Secretary Sheila Widnall presented their vision for the service in the 21st century, writing that it was transitioning from “an air force into an air and space force, on an evolutionary path to a space and air force.”

With the creation of the U.S. Space Force, this path is accelerating and will increase further with a broader migration of missions to orbit.

For example, another one of Kendall’s top priorities is being able to conduct moving-target engagement “at scale.” This includes shifting the ground-moving-target-indication mission from the E-8C Joint Stars and the air--moving-target-indication mission from the Boeing E-3 Airborne Warning and Control Systems—and in some fashion, to space. It is not a new idea; Pentagon projects have explored its feasibility for decades. However, Air Force officials point to recent work with the National Reconnaissance Office, DARPA and private space companies to show momentum for this shift. “We are going to do moving-target engagement at scale both in the air and in space,” Hinote says. “I do think this is an area where the technologies are maturing very fast.”

It will not be a space-only mission. Satellites in low Earth orbit are also vulnerable, and the technology to conduct the mission at that level will still leave holes to be filled by aircraft.

This air and space mix is not unique to moving-target indication, Hinote says. Many other areas will become “aerospace” missions, with a combination of assets in both air and space. This includes, in the near future, tactical-level intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance. Data transport, set to expand in orbit through efforts such as the Space Development Agency’s Transport Layer, will need a backup layer in the air. Many weapons are going to be in both the air and space—a boost glide hypersonic weapon is a space weapon.

The Air Force’s core missions will need to be “domain agnostic”—it will not matter specifically where sensors or weapons are coming from, just that the mission is being done quickly and at scale, Hinote says.

“I think about the core missions that have always been part of our identity. I actually think we’re moving to a time when they’re going to be distributed and shared across air and space,” he says. “And that’s why I like using the term ‘aerospace’. . . . I hope that it comes back into vogue, because that is an area of military power that the United States can leverage against our potential competitors going forward. We’re the leaders there, and we can continue to be the leaders there—and I hope we do [that].”