The U.S. Army’s next scout aircraft could enter service in 2024, six years before the scheduled debut of the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft.

- First ALE enter competitive development

- Operational prototypes' delivery slated for fiscal 2024

The Army’s long-awaited, purpose-built successor to the Bell OH-5D Kiowa Warrior, which was retired in 2015, the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA) in Sikorsky’s and Bell’s respective versions is designed to function as scout rotorcraft, like the OH-58D, roving ahead of ground forces and picking out the enemy’s long-range missile launchers and other formations. But the FARA, unlike the OH-58D, will not be able to perform that mission alone. To survive in the 2030s, the FARA fleet needs its own scout fleet, which the Army now calls Air-Launched Effects (ALE).

“ALE is almost a scout for a scout,” says Dustin Engelhardt, chief warrant officer five and the requirements lead for ALE in the Army’s Aviation Platforms Requirements Determination Directorate.

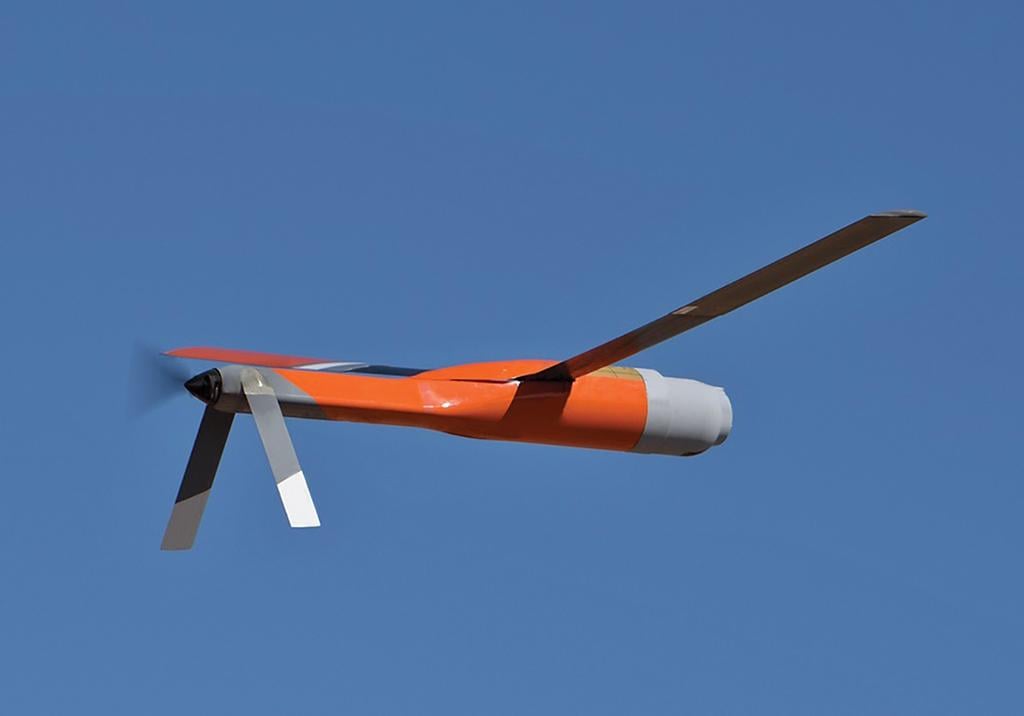

The first ALE could enter service on the Army’s existing helicopter and fixed-wing unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) fleet in less than four years, well ahead of the FARA rotorcraft’s scheduled in-service date near 2030. In August, the Army selected three ALE platform vendors—Raytheon, Northrop Grumman and Area-I—to develop competitive prototypes. Three more companies—L3Harris Technologies, Raytheon Technologies and Boeing subsidiary Aurora Flight Systems—are developing candidate mission systems. Finally, more companies—Raytheon, Leonardo, Technology Service Corp. and Northrop—are competing to develop multiple types of payloads.

The winning companies will develop the first generation of a new kind of aerial platform. Blurring the lines between a traditional UAS and a munition, the Army envisions a new class of ALE that is low-cost enough to be disposable after a single use but valuable enough to potentially be recovered for reuse. The Army’s concept is similar in many ways to the Air Force’s Low-Cost Attritable Aircraft Technology program, also known as Loyal Wingman. But there are significant differences.

The Air Force envisions the Loyal Wingman as capable of roving across hundreds or even thousands of miles of contested airspace, whereas the Army’s requirements call for less range, albeit a similar mission.

As threats to manned aircraft drove the development of a wide range of fully reusable UAS to perform the “dull, dirty and dangerous” missions more than two decades ago, those UAS themselves now need support, by cheaper and more disposable ALE, to perform the same missions.

“When we looked at the capabilities organic to the platform and organic to FARA, and the challenge just to make a rotary-wing aircraft operate survivably [in the future], it puts a lot of additional requirements and complexity to that system,” Engelhardt says. “To that end, we’ve looked at how we can reach out, how we can find those targets and how we can stimulate them to provide some sort of a targetable signature. And, ultimately, how we can degrade and destroy them. So we came up with the concept of [air-launched] effects.”

The Army defines four primary missions for the future ALE: detect, identify, locate and report. As the FARA operates from a safer distance, the crew will launch 4-8 ALE into a hostile area, each with different capabilities. Some will carry electronic warfare payloads, and others will serve as decoys. Others could operate as loitering missiles.

The attritable nature of the ALE will require some performance concessions to cost. “As an example, if I’ve got a payload that can deliver effects at 10 km [6 mi.], can we dial that down and see where the ecosystem still works?” Engelhardt says. “Can we manufacture these things a little bit different than we have previously, so that we can provide that solution that we’re okay with battlefield attrition?”

The volume of ALE on the battlefield will change how the Army operates teams of manned and unmanned aircraft.

“What we don’t want is what we typically see with UAS and manned systems right now: where it’s a steady stream of high-definition video, it’s very data-heavy, network-heavy and requires a lot of input from the operator,” Engelhardt says. Instead, the ALE will “execute a series of preprogrammed and dynamic instructions and report back as needed to the FARA.”

The Army is developing a mesh network to allow the ALE to share data. The processors on the network will select a subset of data most relevant to a host aircraft such as the FARA. The FARA crew could then use the future Long-Range Precision Munition or call in the Army’s surface-launched, long-range precision fires, like the Precision-Strike Missile or the Strategic Long-Range Cannon, Engelhardt says.

Comments