After successfully kicking off its 2022 launch campaign and with just six missions remaining to complete its 648-member satellite constellation, OneWeb was looking forward to rolling out global commercial broadband services by year-end.

But then Russia invaded Ukraine, sparking retaliatory trade sanctions. Suddenly OneWeb, which flew on Russian Soyuz rockets purchased through Europe’s Arianespace, found itself grounded.

- ESA suspends ExoMars partnership with Russia

- Commercial demand for Soyuz launches plummets

Instead of delivering a 14th batch of OneWeb satellites into orbit on March 4, a Soyuz 2.1b rocket was rolled back into a processing hangar at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, and the satellites were offloaded. “We hope they will be returned to us,” Chris McLaughlin, OneWeb chief of government, regulatory and engagement, tells Aviation Week.

No stranger to financial roller coasters—OneWeb emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy less than two years ago—the company pivoted quickly. Eighteen days after OneWeb’s board of directors decided to suspend flights from Baikonur, the company announced a new launch partner, SpaceX, which is building its own low-Earth-orbit (LEO) broadband constellation, Starlink.

OneWeb’s ban on Soyuz launches was in response to a “poison pill” proffered by Russia on March 2 mandating that the UK government sell its stake in OneWeb and that OneWeb guarantee its satellites will not be used for military purposes.

The partnership with SpaceX may seem unusual, given that the companies will ultimately—though not directly—compete for customers. OneWeb targets businesses, governments and agencies, while SpaceX is selling directly to consumers.

“This is not just a race among competitors,” Ruth Pritchard-Kelly, OneWeb senior advisor for regulatory affairs, said at the Satellite 2022 conference in Washington on March 21. “All of us are racing to connect the unconnected.”

“SpaceX will do the right thing for OneWeb, even though they are a competitor,” SpaceX CEO Elon Musk wrote on Twitter.

The terms of the agreement were not disclosed. The intent is for SpaceX to begin delivering the rest of the OneWeb constellation into orbit this summer. So far, OneWeb has 428 operational satellites in orbit, or 66% of its planned 648-member initial constellation.

“We thank SpaceX for their support, which reflects our shared vision for the boundless potential of space,” OneWeb CEO Neil Masterson said in a statement.

The negotiations with SpaceX took just 72 hr., Masterson told Aviation Week on the conference sidelines.

OneWeb launches aboard SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets will take place from Florida, using the polar launch corridor SpaceX reopened in 2020 after a 50-year hiatus. OneWeb plans to modify the Soyuz rocket satellite dispenser, built by RUAG Space, to accommodate the Falcon 9, an industry source tells Aviation Week.

OneWeb and manufacturing partner Airbus are studying what, if any, payload accommodations can be made to take advantage of the Falcon 9’s greater lift capacity. The rocket can carry up to 50,265 lb. into LEO, roughly three times what a Soyuz 2.1b can lift. The polar flightpath from Florida, as well as SpaceX’s preference to return its first-stage boosters for reflight will reduce the Falcon’s lift capacity for OneWeb. The modified satellite dispenser also will be a key factor in how many OneWeb satellites will fly on a Falcon 9.

OneWeb had been launching batches of 34 or 36 satellites on Soyuz rockets flying from Baikonur, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) spaceport in French Guiana and the Vostochny Cosmodrome in Russia’s Far East. The satellites weigh about 330 lb. apiece.

OneWeb began service beta trials in December. The constellation currently offers 70% coverage of the globe, with full coverage in the Northern Hemisphere down to 50 deg. latitude. McLaughlin says the company could begin commercial service with its current configuration, though “obviously we’d like more satellites up.”

A source from the Russian space industry tells Aviation Week that the 36 OneWeb satellites slated to fly on March 4 cannot be returned to the customer through Kazakhstan, which formally leased Baikonur to Russia until 2050. The cosmodrome lacks a Russian customs office, so the satellites must be returned to Moscow’s Sheremetyevo International Airport, which approved their entry. However, as part of the fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Western Europe, the UK, the U.S. and other countries closed their airspace to Russian carriers. Moscow responded in kind.

Dmitry Rogozin, who heads the Russian State Space Corp. Roscosmos, hinted that the Soyuz 2.1b slated to launch for OneWeb can be repurposed for another mission, even though Arianespace already has paid for the Russian rockets and services needed to perform the remaining launches.

All the Soyuz vehicles assembled for the OneWeb campaign are, in fact, the property of the customer, the source tells Aviation Week, so the vehicles will remain stored at Baikonur until another solution is found.

Arianespace Chairman and CEO Stephane Israel declined to comment on the status of the Soyuz launches contracted through Starsem, the commercial arm of Roscosmos.

Russia’s loss of six OneWeb missions will have the largest, but certainly not the only, impact on the country’s commercial launch industry. ESA is seeking alternative launchers for several missions, including its flagship ExoMars rover, which is designed to search for signs of indigenous life on Mars. As part of a partnership with Russia, Roscosmos was to provide launch services aboard a heavy-lift Proton rocket in September.

Rather than heading to Baikonur, the rover is being prepared to be put into storage at manufacturer Thales Alenia Space’s facility in Turin, Italy.

The mission originally was slated to launch in 2020 but was postponed due to technical issues with the rover’s dual-parachute landing system. The flight was rescheduled for this September, when Earth and Mars will next align for interplanetary flight.

On Feb. 28—four days after Russia invaded Ukraine—the ExoMars launch campaign came to an abrupt end. Launching with Roscosmos has become “practically and politically impossible,” ESA Director General Josef Aschbacher said in a statement.

ESA is exploring both European and non-European alternatives for launch. NASA has expressed a willingness to support the ExoMars mission, Aschbacher said.

The next viable launch window after September appears to be 2026, although such a shift would require major changes in the program and would probably involve NASA. The U.S. already is partnering with Europe on another Mars campaign, to return samples being collected by the ongoing Perseverance rover mission.

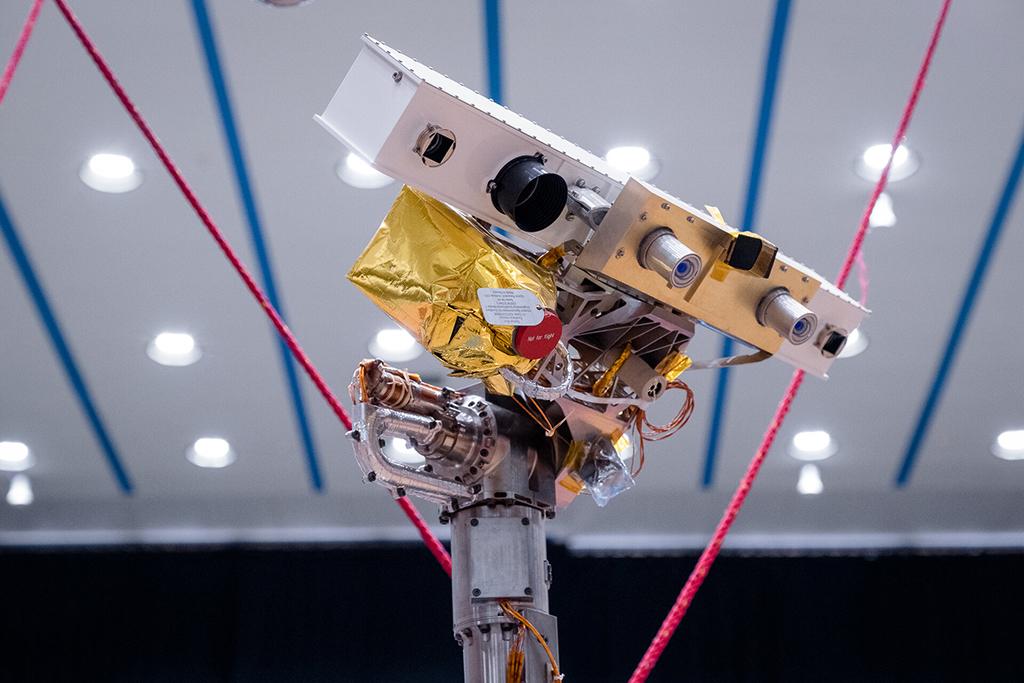

Central to the ExoMars initiative is the Rosalind Franklin rover and its drill, which is designed to dig samples out of the Martian soil. Those samples are planned to be analyzed at the molecular level in an onboard laboratory. The rover includes scientific instruments made in Russia, as well as the radioisotope thermoelectric generators that help it maintain its vital functions during the cold nights. Russia was also the lead for the rover’s landing system, adds David Parker, ESA’s director for human and robotic exploration. Technologies to replace that capability are available in Europe. Some were demonstrated (with partial success) on the failed Schiaparelli Mars lander in 2016.

Meanwhile, ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter, launched in 2016 as the first part of the ExoMars program, continues to gather data on Mars’ atmosphere and relay communications from NASA’s landers and rovers on the planet, ESA says.

ESA’s member states have invested more than €1 billion ($1.1 billion) thus far in the ExoMars program.

As for Russia, Rogozin took to Twitter to announce that Roscosmos will begin work to implement a solo mission to Mars in the very near future. “We will lose a few years but will duplicate our [ExoMars Kazachok] lander, make [an] Angara launch vehicle for it and launch an independent scientific mission from a new launchpad at [the] Vostochny spaceport,” he wrote.

Roscosmos told Aviation Week it was too early to provide any details on this program.

The break with Russia leaves ESA in a particularly vulnerable position, since its new Vega C and Ariane 6 rockets have not yet entered service. The boosters were originally scheduled to replace the Soyuz in 2020.

Soyuz rockets had been scheduled to launch several European satellites in 2022-23 including:

• The French defense ministry’s CSO-3 optical surveillance satellite, slated to launch this year.

• Euclid, a space telescope aimed at understanding dark matter and dark energy, planned to launch in 2023.

• Earthcare, a satellite designed to study the effect of clouds and aerosols on climate, scheduled to launch in 2023.

• Four spacecraft for the Galileo global-positioning constellation prepared for launch this year.

The Vega C rocket might be able to launch some of these satellites. Avio is developing the upgraded light launcher, and Arianespace will operate it. The inaugural flight is planned for May.

Two obstacles must be overcome for the Vega C to replace Soyuz rockets. First, a launch cadence has to be planned and executed. Second, the RD-843 engine for the upper stage is manufactured by Yuzhmash in Ukraine.

RD-843s have been secured for the Vega C’s first three flights, according to Daniel Neuenschwander, ESA’s director of space transportation. For the following launches, “we are assessing different options, preferably from our member states,” he says. European rocket engines are not fully mature, however, so ESA might have to look abroad. “Time is of the essence,” Neuenschwander says.

Another alternative to the Soyuz could be the Ariane 6. The program must pass two major development milestones before it is ready, though. The upper stage has to be fired on a testbed, and a series of dress rehearsals has to be conducted on the launchpad. A cadence must be established, too, notes Aschbacher.

Could the Ariane 6’s inaugural flight, scheduled for late this year at the earliest, carry payloads that were earmarked for the Soyuz? That is not Neuenschwander’s favorite option. It would affect the flight schedule, “and it is equally important to keep that timing and then accelerate the pace to meet the increased need,” he says.

After the first flight, the most suitable version to meet the emerging requirement will be the Ariane 62, the version with shorter fairings, he adds. The medium-lift Ariane 62 is equipped with two strap-on boosters (in lieu of the Ariane 64’s four boosters). It can use two fairing variants, 14 m (46 ft.) or 20 m long.

For other missions, several micro- and minilaunchers in development in Europe will be considered. Overall, “we are looking at European launchers, and when we see a gap we will evaluate non-European options,” Aschbacher says.

ESA member states also will soon miss Russian raw materials for satellite construction, including xenon for electric propulsion systems and titanium for associated tanks, Aschbacher notes. “ESA is working out a list of its Russian dependencies,” he says. “We need time to find a way forward. We will make proposals for each item.”

A meeting of member states at which to make decisions on launches and supplies is being organized for April.

Losing OneWeb and ESA as customers will cut Russia’s launch manifest to about 20 launches this year—about one-third of what was expected prior to the invasion.

Russia has launched five times this year: a military mission in January; the launch of 34 OneWeb satellites in February (which took place from ESA’s spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana); the Progress MS-19 cargo mission to the International Space Station (ISS), also in February; and the crewed Soyuz MS-21 flight and another military launch in March.

Roscosmos’ next launch is expected no earlier than June 3, when the Progress MS-20 cargo capsule will head for the ISS. A source from the Russian space industry confirmed to Aviation Week that Roscosmos was keen to keep all ISS-related missions planned for this year. They include another Progress cargo mission in October and the crewed flight on Soyuz MS-22 in September.

The source also said that Russia planned to increase its satellite constellations this year, launching Gonetz-M, Luch and Glonass communication and navigation satellites, Meteor-M and Electro-L hydrometeorological spacecraft and the Ionosfera space probe.

Russia’s largest scientific effort will be the launch of the Luna-25 uncrewed lander to the Moon in July.

Roscosmos still hopes to make at least two commercial launches this year, the source said. Korea Aerospace Industries’ CAS500-2 satellite for precision ground observation, together with some secondary payloads, is expected to be orbited by a Soyuz 2 rocket from Baikonur in the third quarter.

Another spacecraft—the AngoSat-2 communication satellite assembled by Roscosmos for Angola—will be launched from Baikonur by a Proton heavy-lift rocket.

Additional military launches are likely to be performed by the Russian Aerospace Forces from its spaceport in Plesetsk in northwest Russia.