The D-Orbit experiment tests Amazon Web Service’s ability to filter out useless satellite images.

Amazon Web Services is best known for its data centers on Earth, but in recent years, the cloud-computing company has started investing off-world.

In fact, the Seattle-based subsidiary of Amazon.com, the giant e-commerce website, has the largest market share of cloud-computing services on terra firma, ahead of rivals such as Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud. It sees space as the next frontier for computing.

- Bandwidth issues spur development of greater computing capacity in space

- Data center pioneer sees diverse uses for its artificial intelligence software in space

“We’re sitting in this really interesting inflection point, where technology, including the cloud, I would offer, has really opened the aperture of what we can do in space in the future,” says Clint Crosier, director of the Amazon Web Services (AWS) aerospace and satellite business.

The company envisions that by reapplying some of its cloud-computing applications, including artificial intelligence programs, to edge-computing processors in space, it can liberate satellites, spacecraft and space stations from bandwidth limitations and latency problems that come with radioing data back to Earth.

Edge computing is a model in which data processing and storage are conducted close to the point where the data is generated or needed, reducing bandwidth requirements and latency that come with sending information to faraway data centers.

Increasingly, far more data is collected in space than can be downlinked back to the ground, meaning operators are unable to realize the full potential of their hardware in space. That problem is made worse when data sent back to Earth is unusable.

“In the imagery business, it’s pretty standard that when you fill the buffer on the satellite and then download all that data, only 70% or 80% of that data will actually be usable,” Crosier says, noting that in some satellite images clouds and smoke can obscure views of the Earth. Wasting radio-frequency bandwidth on unusable images has financial and opportunity costs to satellite operators, he says.

“People always want more images than the buffer can hold. Every time you fill your buffer, you’ve told some other customer, ‘I can’t get your image in this cycle, but I’ll try to get it in tomorrow,’” Crosier says.

To avoid bandwidth and latency problems, AWS is experimenting with providing computing at the edge—on the very spacecraft that collected the data in the first place. Last year, as part of a demonstration, the company processed images of Earth using machine learning software programs running on a computer hosted within D-Orbit’s ION Satellite Carrier SCV004, an orbital transfer vehicle in low Earth orbit. AWS’ machine learning software was used to automatically identify objects such as clouds and wildfire smoke, as well as buildings and ships.

“We looked at cloud cover, and we looked at other obscura onboard on the satellite using edge computing with [artificial intelligence and machine learning],” Crosier says. “When the edge-computing device determined that it was out of tolerance, it would do one of two things: It would either excise the clouds [from] the imagery and then just send you down the parts of the image that were usable; or, if that wasn’t enough it would tell itself, ‘this image is no good.’ It would discard it, and then it would take the next image in the customer queue.”

By cutting out pieces of images or ignoring entire images, AWS was able to reduce the amount of data the spacecraft sent back to Earth by 42%, Crosier says.

Back on Earth, AWS already provides cloud-computing services to the space industry—for example, to satellite companies such as HawkEye 360, a radio-frequency-sniffing satellite operator that used the Amazon SageMaker Autopilot program to build machine learning models for geolocating ships that may be illegally fishing, trafficking humans or smuggling goods.

AWS aims to provide some foundational capabilities and then work with partners and customers to create custom software and hardware. D-Orbit of Italy and Unibap of Sweden—whose computing system was used in the recent demonstration—are part of the AWS Partner Network, a group of qualified users and vendors of the company’s cloud-computing services.

By keeping software consistent across terrestrial data centers and space-based edge computers, AWS aims to leverage the network’s more than 20 million software developers, Crosier says.

“One value of running the same software at the edge as customers use in the cloud on Earth is that customers don’t need both Earth-system software developers and satellite-specific software developers,” he says.

Over the past three years, the company also has attempted to boost use of its software in the space sector by running its “Space Accelerator,” a program to help startups use AWS products in space. To be sure, computing in space is not the same as on Earth. Unibap, whose SpaceCloud IX5 was used for the edge-computing experiment, says making a computer run reliably in space can be “really challenging,” particularly because electromagnetic radiation, drastic temperature changes and the vacuum of space can wreak havoc.

“The secret recipe to make this happen is not one simple thing but a combination of many. It all starts with selecting radiation-tolerant components that are suitable for the environment while consuming as low power as possible,” Unibap says. “In addition, you need to deal with the fact that the computer operation, regardless of chosen architecture, will be affected by single-event functional interrupts due to radiation and must be corrected and mitigated in run-time.”

Not all environments in space will require special computers, however. Last year, AWS also sent its Snowcone solid-state-drive device, an edge computer designed for use on Earth, to the climate-controlled International Space Station (ISS). The off-the-shelf computer was qualified for space and launched as part of Axiom Space’s Ax-1 mission, the first all-private astronaut mission to the space station, for processing experiment data.

Typically, radioing experiment data from the ISS back to Earth can take up to 24 hr. But with the Snowcone device onboard, experiment data was able to be processed in 20-30 min., Crosier says. “Instead of running one experiment every 24 hr., you can essentially run an experiment every hour or two,” he says.

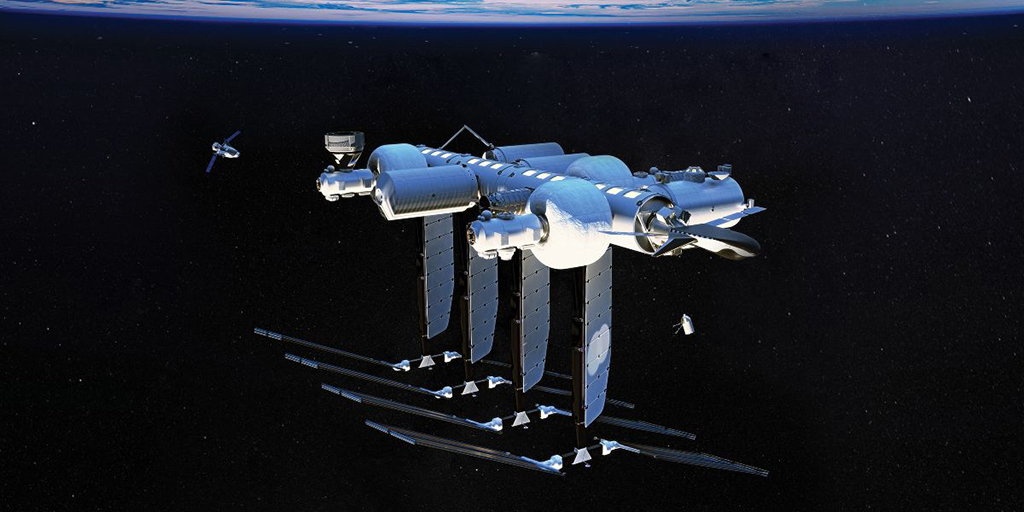

Edge computing—and artificial intelligence—also could be used to automate in-space servicing, assembly and manufacturing, Crosier says. AWS is supporting Blue Origin and Sierra Space’s Orbital Reef, an in-development commercial space station billed as a “mixed-use business park” for conducting research and manufacturing goods. AWS is working with Japanese space-robot manufacturer Gitai to monitor the health of its robots and record telemetry data from its robotic arms. Gitai aims to use its robots for in-space servicing, assembly and manufacturing, as well as lunar resource exploration and lunar base development (AW&ST Jan. 16-29, p. 60).

Ultimately, will AWS establish a parallel cloud-computing infrastructure in space? Will the company launch and operate orbiting data centers connected to each other, as well as other satellites, spacecraft and space stations, via a network of laser communications systems?

The question is “prescient,” Crosier says. “You can hypothesize some of the things that we’re talking to our customers about and some of the things we’re thinking about,” he says. “We don’t have any announcements to make today.”