Airline Industry Starts High-Risk Relaunch

The airline industry is used to some level of guesswork, even in good times. No one really knows how demand will evolve, whether a new route will actually perform according to expectations or what the response by competitors will be. No matter how analytical the approach is, no matter how experienced the network planning department, some experiments will always fail.

In good times, airlines typically have the financial wherewithal to deal with some level of underperforming markets. But now, as the industry takes its first steps to emerge from an unheard-of crisis, it faces the worst possible combination: There is no financial margin left for wrong bets on capacity, pricing and network rebuilding, and the uncertainty about when, where and how demand might return is greater than ever.

- More travel restrictions fall and markets reopen

- Expensive restart phase full of risks

- IATA warns its forecast may have been too optimistic

Only over the past few weeks have some encouraging signs begun to emerge on a broader scale, probably good enough to call the short-term trend a recovery, but not good enough to call it stable upward development. And even as traffic begins to slowly come back, airlines will soon face the winter season, when most carriers lose money even when business is booming.

The path forward for commercial aviation depends on one factor first and foremost: an airline comeback based on the return of traffic. Everything is tied to it. When that regains traction, airlines will be able to afford to pay for maintenance and spare parts, resume airport and air traffic control payments and bring back pilots and cabin crew from short-time work schemes that, in many countries, have protected them from being laid off for now. If things go really well, airlines may even consider taking delivery of aircraft in greater numbers—aircraft ordered when some executives imagined continued profitability at least until their own retirements.

Unfortunately, while prospects for the airline industry differ by region, worldwide there is reason for renewed concern. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) warns that a recent rise in COVID-19 cases led to a weakening of bookings in the second half of June and could have a severe impact on the expected recovery of air travel.

A COVID-19 outbreak discovered in Beijing on June 11 has shown what airlines might expect even in countries that have the pandemic largely under control. News of the outbreak prompted outsiders to avoid travel to Beijing, while the city’s government forbade people from zones of high infection to leave. The authorities also discouraged departures by people from other parts of Beijing and made them conditional on having had recent, negative infection tests.

By the last week of June, Beijing Capital International Airport was handling only about a quarter as many flights as it had three weeks earlier.

IATA Chief Economist Brian Pearce says the recent increase is leading the association to be “cautious about prospects for the next few months.” If it continues, it could delay the ending of travel restrictions for international journeys “beyond what we had expected in the forecast.” The European Union’s decision to keep travel restrictions to the U.S. in place is one major point of concern, given that U.S. international flying represents 37% of global demand, as measured in revenue passenger kilometers (RPK).

Pearce points out that there is a large downside risk for the expected rebound in air travel. IATA so far forecasts demand to recover to a level around 36% below 2019 by year-end. But if the rise in novel coronavirus cases is not reversed and travel restrictions remain in place, the actual drop in air travel could be 53%.

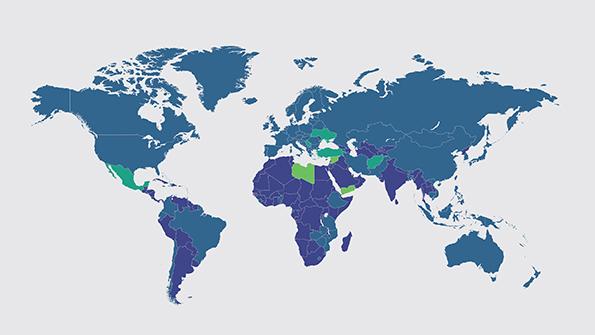

According to an IATA analysis, around 20% of countries are starting to ease restrictions—but 65% remain completely closed. Where massive state bailouts have been put in place, airlines have largely avoided bankruptcies. “In the absence of substantial government aid, it is very difficult for airlines to survive,” says Pearce. Latin America is the most dramatic case, where LATAM Airlines, Avianca and Aeromexico all filed for bank-ruptcy within weeks.

“Ultimately, until we have a vaccine, one of the suppressors of demand for travel will be the perception of risk on the plane,” says Patrick Edmond, managing director of consultancy Altair Advisory. “Reassuring passengers about safety is going to count for at least as much as headline prices.”

The number of COVID-19 cases, which is rising particularly fast in parts of the developing world and the U.S., is not the only reason for concern. While businesses expect a V-shaped recovery of the economy in general, that does not translate into an equivalent rebound of air travel demand, as it should in normal times. “[Corporations] are still very cautious about travel,” Pearce notes. But there “may be some upside surprises,” he adds. In contrast to business confidence, consumer confidence is still very low. For leisure travel to pick up in any significant way, the industry will need to reverse such apprehensions.

So far, IATA continues to predict that the industry will return to profitability in 2022, with a relatively steep recovery of global airline traffic to a level 36% below 2019 by year-end and 29% below 2019 in 2021.

Global traffic figures for May show a 91.3% reduction over last year, compared to a 94% drop in April. “May was not quite as terrible as April. That’s about the best thing that can be said,” says IATA Director General and CEO Alexandre de Juniac. Essentially all of the recovery came from domestic travel, particularly within China. There was “no improvement at all in international travel,” Pearce notes. IATA members also recorded an all-time-low load factor of 50.7% for the month, a decrease of 31 percentage points compared to May 2019.

Beginning in June, though, many airlines started rebuilding capacity. A bet was placed on the future.

In the U.S., with international travel set to lag domestic in the absence of a vaccine, domestic-focused carriers such as Southwest Airlines will have a natural advantage over their competitors with larger international networks. Prior to the pandemic, Southwest deployed roughly 5% of capacity outside the country, compared to full-service carriers that devote as much as 40% of their capacity to international flying in normal years.

Southwest expects to operate at nearly flat year-over-year capacity by year-end, indicating an aggressive strategy to capitalize on its domestic network and low-cost structure during the COVID-19 recovery. Delta Air Lines, with far more exposure to battered corporate and long-haul markets, plans to steadily grow its domestic schedule back to 55-60% of last year’s levels by September, before taking a strategic pause while management evaluates fall demand trends.

American Airlines and United Airlines are planning to push their domestic flying above 50% in July and August, respectively. Still, with so much uncertainty surrounding the return of corporate and international traffic, it is likely that the largest carriers will remain deep in negative year-over-year capacity territory until spring 2021, when the base for comparison will also have been affected by the pandemic.

Ultra-low-cost carriers (ULCC) believe their domestic leisure focus and low operating costs will allow them to grow aggressively during the recovery period, a scenario reminiscent of the years following the 2008 financial crisis, when they expanded while network carriers adhered to strict capacity discipline. Allegiant Air and Spirit Airlines are both targeting nearly flat levels by year-end, while Frontier Airlines is aiming for 80-90%. ULCCs such as Allegiant and Sun Country Airlines will also benefit from low-priced used aircraft. The CEOs of both companies have said they will use them to source fleet growth and spare parts for their Airbus A320 and Boeing 737 fleets, respectively.

American Airlines and Delta have already retired more than 350 aircraft combined, including all of American’s A330s, Boeing 757s, 767s and Embraer 190s and all of Delta’s MD-88s, MD-90s and Boeing 777s. United has not retired any aircraft, but has parked hundreds temporarily while executives seek more clarity on demand trends.

In Europe, a recovery is underway. According to Eurocontrol data, the number of flights in the network was 12,742 on July 1, about four times the level of just a week earlier. “The recovery is clearly gathering speed,” says Eurocontrol CEO Eamonn Brennan.

But that growth is still a drop in the ocean compared to precoronavirus levels, and airlines and consumers alike are cautious about how the next few weeks and months will play out. And not everyone benefits equally, with UK-based airlines still struggling with quarantine rules while some, such as Virgin Atlantic, desperately seek more equity.

“On the positive side, there is pent-up demand coming into the summer. Lots of people would like to be able to go away on holiday,” says Edmond. “In Europe the main driver this summer is going to be leisure, not business.”

“We would expect a second [COVID--19] wave, should it materialize, to be met with a more granular approach by authorities instead of nation-wide shutdowns,” says Bernstein analyst Daniel Roeska. “This should enable airlines to react proportionally and not bring the entire air travel system in Europe to a standstill again.”

With demand for air travel tied closely to a country’s economic situation, however, airlines are also going to have to make huge concessions on profitability and the all-important ancillary revenues by luring in wary consumers with low prices. It is a message the region’s LCCs have already taken to heart. EasyJet said it was launching its biggest summer sale ever as it mapped out the partial resumption of its schedule, with over 1 million flights starting at £29.99 ($38), highlighting the intense pricing pressure it and its peers are facing.

EasyJet has said it expects to be operating at about 30% of its normal pre-COVID-19 capacity in the fourth quarter of its financial year, which runs through the end of September. Ryanair, meanwhile, returned to 40% of normal flight schedules July 1, with a daily flight schedule of almost 1,000 flights, restoring 90% of its pre-COVID-19 route network.

Lufthansa plans to fly to 90% of its domestic and European destinations as well as 70% of its long-haul markets by September, albeit at around 40% of precrisis capacity, so at a much lower frequency.

“I think in the best-case scenario, by the end of the summer if we’re back to 50% of normal demand, that would be spectacular,” Edmond says.

Beyond the financial and psychological factors affecting passengers, there are operational and financial risks to contend with for the airlines too.

French Bee CEO Marc Rochet says the increased costs and unpredictable revenues of the post-coronavirus ramp-up phase could be fatal to some airlines. “The sleep phase cost a lot of money, but most airlines were able to absorb that,” he says. “The takeoff phase, however, could be fatal for some airlines because no one knows how long it will last.”

“Adapting to the change in demand and the weaker medium-term outlook requires airlines to cut capacity by 10-20%,” Roeska writes. “This requires renegotiation with aircraft OEMs and the labor base. The upcoming weeks will demonstrate how successful airlines can shrink their business without carrying too many planes or employees through a crisis that will be felt until 2023-24.”

In the Asia-Pacific region, domestic markets have been rebounding well as internal restrictions have eased, and the strongest growth tends to be in countries that have been most successful in controlling the pandemic. The top 10 domestic markets as measured by seat capacity are all in the Asia-Pacific region.

Vietnam, for example, has seen its domestic capacity surge back quickly after essentially disappearing in April. Markets such as India’s have progressed more slowly, with the Indian government capping domestic capacity since flights resumed on May 25.

The rapid recovery of domestic markets is likely to continue through this year, providing some relief for airlines in the absence of international traffic. Of course, this is cold comfort to airlines such as Cathay Pacific and Singapore Airlines (SIA) that do not have domestic networks.

International recovery has been more sluggish in the Asia-Pacific region, which is relatively fragmented due to the vast number of countries and a relative lack of intraregional authorities. Some airlines have begun ramping up international flights this month, including Korean Air and the major Japanese carriers. But the key factor will be how quickly cross--border restrictions and quarantine requirements are eased.

A few countries have established travel corridors—or fast lanes—-between them for essential travel. South Korea and Singapore both have such arrangements with China. More of these are likely to emerge, first on a bilateral basis and then multilaterally. The next step will be the development of travel bubbles, which would allow nonessential travel with few restrictions. The first of these could be established between Australia and New Zealand later this year.

The Hong Kong and Singapore governments have allowed transit flights to resume, which will put SIA and Cathay in a good position to take advantage of global markets as they reopen. A crucial factor for many Asia-Pacific airlines will be gaining more access to China routes, which have been heavily restricted by the Chinese government during the pandemic.

Varying levels of government support will play a key role in determining which airlines emerge strongest from the COVID-19 crisis. For example, SIA’s S$15 billion ($11 billion) state-backed financing package will give it an advantage. In contrast, the Thai government’s decision to send Thai Airways to bankruptcy court to restructure shows that governments have less appetite to provide money to airlines with poor financial records. Some Asian nations are still considering airline bailout packages.

Airlines in the region are also pulling whatever levers they can, and many have launched restructuring initiatives or broad strategic reviews. Some of these airlines had already started—or recently completed—turnaround programs, but the new reviews are likely to go much further and yield broader changes. They will examine areas such as workforce, fleet and network as they look to streamline their businesses.

There likely will be some airlines that do not survive the crisis. Many of the region’s flag carriers have previously been considered too big to fail, but the massive government spending necessitated by COVID-19 could challenge that assumption.

For now, smaller LCCs appear more vulnerable, particularly those that have not benefited from state bailouts that flag carriers have received. The long-haul LCCs could be particularly at risk due to their reliance on international routes and widebody aircraft. NokScoot is one LCC that has been closed down by its owners, and Tigerair Australia will likely soon follow.

FLIGHT PATHS FORWARD

Optimistic

- Better business confidence indicators translate into greater demand for flying.

- With COVID-19 better contained, supported by an efficient vaccine from early 2021, leisure travel returns more quickly than expected as airlines benefit from pent-up demand.

- Airlines surviving with government help benefit from a consolidated market; can establish higher pricing earlier.

- Short-haul flying recovers almost fully in 2021; long-haul returns by 2023.

Neutral

- More countries manage to contain the pandemic, and the industry’s health measures prove to be efficient.

- Air travel returns to 40% below 2019 levels by the end of 2020, recovering further in 2021.

- Long-haul flying remains severely suppressed through 2020 but makes a steep recovery in 2021.

- A COVID-19 vaccine is created, though the effects of a global recession continue to affect demand.

- Traffic returns to precrisis levels by 2023; the industry makes its first post-coronavirus profit in 2022.

Pessimistic

- Containing the further spread of COVID-19 takes longer than expected and affects major air transport markets such as the U.S.

- Bookings weaken and international travel restrictions remain in place longer or are reinstated.

- Traffic recovery is delayed and much weaker than forecast; more airlines fail; aircraft production is cut further.

- Slow recovery begins only in 2021

- after a vaccine reassures travelers.

- A return to 2019 traffic levels is achieved after 2023.