In many ways, Asia’s aviation challenges derive from a problem most of the world would love to have: rapid market growth. Despite some headwinds, that is not likely to slow much in 2015. Although the growth is potentially limitless and continues to be rapid, matching supply and demand in such a dynamic market involves massive financial risk. In the process, as lowcost carriers (LCCs) intrude further into the core of the system, that risk is compounded by the fundamental disruption of traditional services that is occurring.

Peter Harbison, Exec. Chairman CAPA

For the Asian system has changed much faster than any other before it. Just ten years ago, there was effectively no low-cost airline operation in the region, outside Australia. All national markets were dominated by large full service flag carriers. Today, astonishingly, nearly 60% of intra-southeast Asian seats flown are on LCCs – much higher than Europe (42%) or the US (31%), where it all began.

It is the more remarkable because much of the capacity is, unlike the rest of the world, in the highly complex and restrictive international market. The turbulence is being driven by a combination of high rates of capacity expansion and, importantly, by new entry.

Each new entrant adds algebraically to the level of competition; many of them are in fact subsidiaries/joint ventures of existing legacy brands, although there are also some big independent additions like Lion Air and its various entities (with 549 aircraft orders). Other airlines like VietJet (with 19 aircraft and a modest 61 on order) have aspirations for expansive growth.

It is the new entry and the constant jostling for position that intensifies the financial risk profile of the Asian industry. It is not enough simply to establish a place in the market; strategically it is almost an imperative for an airline group wishing to establish for the long term to expand at a greater rate than prudence would dictate. Growth takes on a high priority, because in these dynamic markets failing to grow in the short term can mean being excluded from the market in the medium-term.

Overcapacity

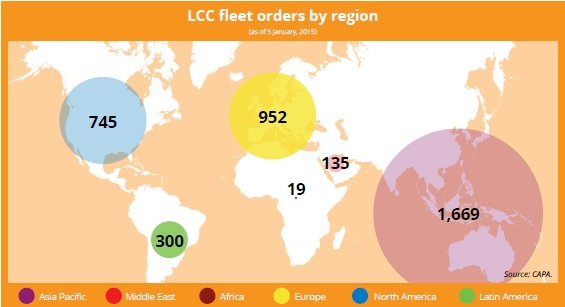

That goes part way to explaining the extraordinary size of order books for airlines in the region. Asia Pacific LCCs account for almost half of the world’s LCC aircraft orders – 1,669 according to CAPA’s Fleet Database – and a higher proportion of them will mean incremental growth rather than replacement of older equipment. Excitement Central has been southeast Asia – until last year, when the party slowed, at least temporarily.

Overcapacity had impacted Singapore’s LCC sector, pressuring yields for all airlines and resulting in unsustainable losses. Singapore’s two home grown short-haul low-cost carriers, Jetstar Asia and Tigerair, had both been unprofitable since early 2013 as the market failed to absorb a surge in capacity. But, in the second half of 2014, Tigerair began to reduce capacity while Jetstar has greatly reduced its rate of capacity expansion (growing only through higher utilisation) without increasing its fleet.

Already a globally renowned transfer hub – for full service airlines – Singapore has, as a result, become one of the centres for LCC transfer connectivity. Following neighbouring Kuala Lumpur’s example, where AirAsia and AirAsia X already connect as much as a third of their passengers, Singapore’s LCCs are now looking towards more transfer traffic to cement their positions.

This evolution from the original, essentially point-to-point LCC concept, is hardly surprising. The Singapore-based LCCs are each affiliates or subsidiaries of full service airlines (Singapore Airlines and Qantas), working almost as surrogates for their parents as they chase the lower yielding passenger, enabled by lower costs. The Southeast Asian market should therefore start to improve in 2015, driven by capacity adjustments and increased traffic flows from partnerships.

Liberalisation

However, the increasingly interesting story of this massive industry disruption is at last gathering pace in the northeast of the region. There the penetration by low-cost airlines is still very low. Only 13% of intra-northeast Asian seats are on LCCs. China, which one day will dominate world aviation, is accelerating its regional presence, while others in the north are also moving.

Both Japan’s and Korea’s LCCs are spreading their international wings more widely and the relatively liberal access regimes in place now (China’s is still restrictive) make that process easier. Thanks to a policy change by China’s CAAC, home grown low-cost airlines are now being encouraged, where previously they were prohibited; the international impact will take some time to filter through, but the medium term effects will be profound and domestically they will cause change. Greater efficiencies, more city-pair operations, accompanied by a flow of new airlines, all contribute to the foundations for a regional system that will look very different by the end of this decade.

Across the region, the spread of several regional LCC brands will generate increasingly competitive conditions as their paths cross more frequently. This will not be a comfortable and predictable growth pattern. But it will stimulate enormous economic benefits and, for those who dare, even bigger opportunities.