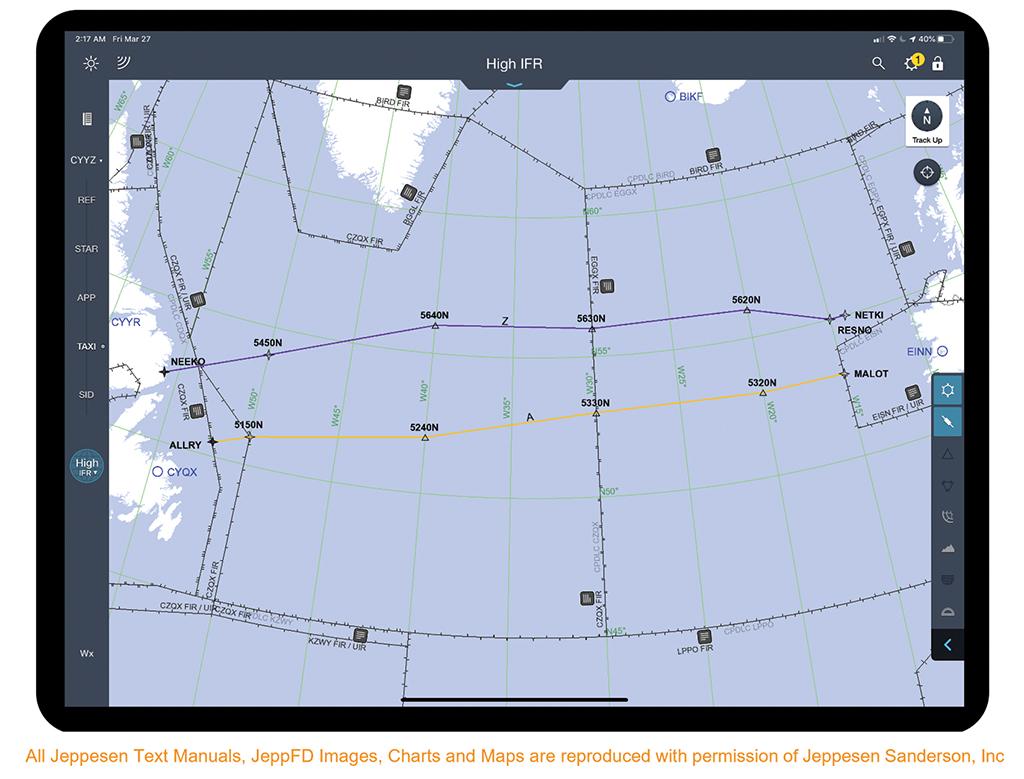

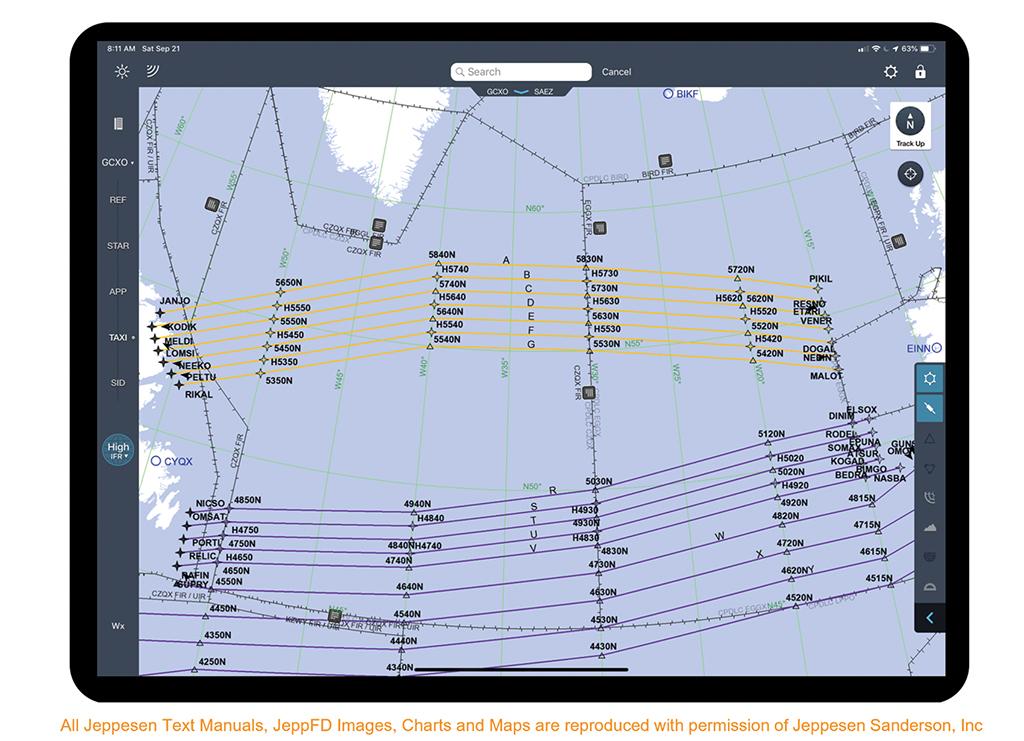

Of all international business aviation operations, 80% involve trips between North America and Europe. Despite mutual political rivalries, business flows uninterrupted in both directions across the Atlantic, but certainly has been slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless the routes remain intact and accessible by business jet.

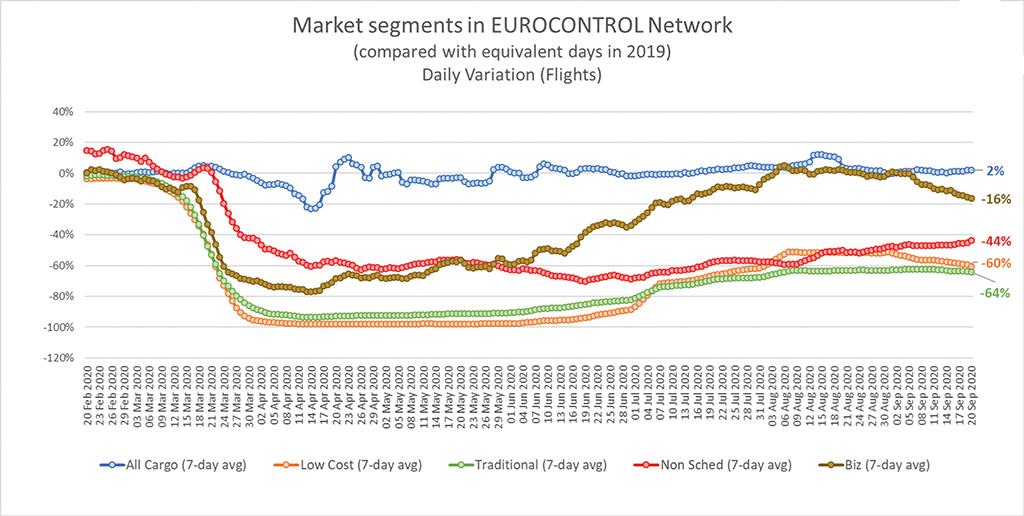

And while passenger airline traffic in the North Atlantic has declined 70%, in Europe this spring, the relative percentage of business aviation traffic tripled from its normal (pre-COVID) level. However, it was a different story from March through May during the early and worst stages of the pandemic. According to Athar Husain Khan, secretary-general of the European Business Aviation Association (EBAA), business aviation was “hit pretty hard. We were tracking -55 to -60% of market presence compared to last year.”

On the other hand, the Europeans also saw a recovery during the spring that was quicker and steeper than the airlines. “We were almost at a par in August, almost at the same levels as a year ago. Very recently — over the last couple weeks [in September] — we were seeing a slight deterioration, down to -16% compared to 2019. What we are seeing in Europe is a drop in the operations of the larger business jets. Lighter aircraft are probably in better shape. In general, compared with the airlines, the figures are a lot better but are still not where we want to be.”

So the trend during the pandemic is that business aviation activity has increased as airline activity decreased. The only segment of commercial aviation that is thriving on the Continent is airfreight, as the COVID-19 lockdowns have made European residents more dependent on web-based shopping for just about everything, and a lot of commodities are being delivered by air.

Business Aviation to the Rescue

One reason for the business aviation surge in Europe — just as in the U.S. — is humanitarian support: medical flights, repatriation, donor transportation, and delivering supplies like COVID-19 tests and personal protective equipment (PPE) to medical facilities during the pandemic. Such activity “normally accounts for 9 to10% of all business aviation in Europe but climbed to 25% at the height of the pandemic,” Khan said. He also confirmed some “new potential in people trying business aviation who haven’t before.” As a result, charter operators are receiving more queries than under normal circumstances.

In the European tourism and travel sectors, representing 22 million jobs depending on the country and its GDP, “there are some that are heavily dependent and some that are less,” Khan observed. “And if you look at the range it is between 4.5% and 25%, depending on how reliant they are on travel and tourism — particularly the coastal countries in Southern Europe.”

There are approximately 4,000 business aviation aircraft based in Europe: About one-third (1,300) are turboprops; light jets number about 1,000; midsize jets tally about 500; heavies account for another 1,000; and the “business liners” (converted airliners like the BBJ and A319CJ) tally 100 aircraft.

At the Brussels headquarters of the European Organization for the Safety of Air Navigation — or Eurocontrol — Ken Thomas witnessed “a tremendous drop” in traffic over Western Europe as the pandemic kicked in. “On April 22, the peak was 4,500 flights, or 15% of normal,” Thomas, who heads the director’s office of Eurocontrol’s Network Manager Directorate, related to BCA. The agency’s raison d’etre is massaging flow control for 41 member-states in Europe plus two associates in Africa and the Middle East.

“At that time, the Network Manager began a recovery program, as we had to support the flights still operating, mostly cargo and business aviation, over the most efficient routes,” Thomas, a Swede who began his career as a controller, explained. “The other thing we focused on was to be sure we had a grip on how traffic would recover to ensure sufficient capacity in the airspace and at airports. We could not afford the ATM network being a bottleneck for a recovery.”

In response to the emergency, the Directorate activated the European Aviation Crisis Coordination Center and assembled a recovery cell that meets weekly consisting of the air navigation service providers (ANSPs) of the member states and representatives of airspace users and airports. “With them, we looked operationally at the resilience of capacity and stakeholder ATC centers,” Thomas said. “We got the operators to approve a plan for four to six weeks out so we could plan ahead for more or less capacity.” Less is important, too: what was needed and what could be kept in reserve. “We have around 50 people online at each meeting.”

June 2020 peaked at 6,500 flights, and on Aug. 28, Eurocontrol enjoyed a peak day of 18,800, or 49% of the same day in 2019 when 37,000 flights were logged. “So we were seeing a partial recovery,” Thomas said.

Differing COVID-19 Rules

During the pandemic, states maintain their own rules regarding which aircraft and passengers they allow across their borders. Just to make things interesting, these change every week, dependent on quarantines.

“Now the recovery has slowed down and retracted a bit due to the ‘second wave’ of infections sweeping across Europe,” Thomas said. “There is reluctance among the traveling public to book trips, as they can’t plan ahead due to quarantines being imposed in their countries. So, now we are seeing yet another reduction in traffic — now looking at peaks of 17,500 flights for October, which is down to 45% of normal. Ryanair flies the most right now, 1,300 flights per day. Next is Easyjet, followed by Turkish Airlines and Air France.”

Guy Gribble, retired American Airlines captain and founder of the International Flight Resources procedures training company, elaborated on the unique and fluid restrictions European countries are imposing in response to the changing impacts of the pandemic. “Countries are coming up with various COVID restrictions,” he said. “Approved countries can be entered without any test or quarantine — a ‘white list’ allowing free transit. A supplement to that is that some countries may require a 14-day quarantine.

“Some will not require the quarantine but will require a COVID test valid within the previous 72 hr. before entering,” he continued. “The validity period is measured backward from the time you’re standing in front of the quarantine officer. You will need documentation for the test; some may require an entry form with the test documentation stapled to it for passengers. However, 98% of these countries do not require this for crew if they are sequestered in the airport hotel where they can rest, eat and then leave.” Note that this mostly applies to charter ops.

Eurocontrol is trying to see “that those who want to fly can do so,” Thomas said. “In general, the delays across Europe are super small. So, there are no revised procedures [at Eurocontrol] but an ongoing commitment to zero delays.” On Sept. 29, close to 15,000 flights were filed, less than half on the same day in 2019. Delays were running at 1,660 min. — 900 alone from weather at Istanbul — compared to 50,000-60,000 min. last year. “Other than the reductions,” Thomas pointed out, “it is business as usual if you have the passengers, and that depends on the various restrictions that different countries are setting out for passengers and flights.” To support more operations, as a daily service, Eurocontrol publishes a summary of COVID-related NOTAMs, “all in one place” at the Network Manager Operations Portal, which can be found on the Eurocontrol website at http://www.eurocontrol.int

What Arrivals Can Expect

“At EBAA at the onset of the pandemic,” Khan said, “we established a resource center on our website [http://www.ebaa.org] that is updated regularly with lots of hands-on operational information on curfews and operational restrictions. Have a good look at that if heading over.” A key piece of information to know, Kahn emphasized, is to ensure that all passengers are “entitled” to enter Europe with respect to the pandemic and individual country restrictions. Note the requirement for masks and quarantines for specific countries. Operators should conduct this research before filing for any destination in Europe.

At the regulatory level, business aviation is confronted with a patchwork of conflicting restrictions, “so what the industry is doing,” Khan reported, “is pushing hard at the European registry level for a harmonized approach: ANSPs, airports, business operators and airlines. This is directed at the highest levels in Europe, including the European Commission and the individual countries of the EU. It is difficult to do this, as many countries are of the opinion that health is a national competency, a prerogative of the national government, not the EU, and they don’t coordinate.”

A good source of information on flying into Europe during the pandemic is Ops Group (visit https://ops.group/blog/europe-covid-travel-rules/). Some points from a recent Ops Group posting:

The U.S. is not included on the EU “safe list” of non-euro countries from which the EU recommends allowing nonessential inbound travel. And it probably will not be added by the time this is published.

In early fall, the safe list included Australia, Canada, Georgia, Japan, New Zealand, Rwanda, South Korea, Thailand, Tunisia, Uruguay and the Schengen Associated States (i.e., non-EU members) of Switzerland, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway. China may be added to the list if it offers a reciprocal deal for EU travelers. As did Khan, Ops Group notes that there is considerable variation in the internal rules imposed by individual countries.

Some Euro states only consider where you are flying from as opposed to the nationalities of passengers aboard the aircraft. (This is the opposite of the U.S., which is only concerned with where the passengers have been within the previous 14 days.)

Intra-Schengen freedom of movement is still largely in place, i.e., most Schengen countries are still open to entry from other Schengen countries, and here is the basis for one of Ops Group’s famous workarounds: “If you can get into one, you’re more likely to access others.” (Hold that thought.)

Where that does not work, many countries are still allowing direct flights from the U.S. under the caveat of “business purposes.” As of mid-October, these countries were Austria, Belgium, Bosnia, Croatia, Denmark, Italy, Montenegro, the Netherlands, Serbia and Spain.

Here’s another Ops Group workaround, and it concerns getting into France, where, again as of mid-October, passengers flying from the U.S. directly to France could only do so for “essential” reasons, backed up by an “international travel certificate” (a form passengers need to fill out). But, according to Ops Group, “travelers from the U.S. can dodge this ban by flying to the UK first, do a quick stop there, get your passport stamped, and then fly straight on to France.” This loophole works because the French rules are based on where the operator flies from, not the operator’s nationality or where the flight originated. A quarantine is avoided with proof of a COVID-19 test and completion of a Public Health Passenger Locator Form.

Italy is another story: Ops Group characterizes the entry rules there as “horribly complicated.” While there are a few ways U.S. passengers can enter Italy, the most popular one is for “business purposes” — but in this case operators will need prior approval and an invitation letter from a local business. Maximum ground time allowed in-country is 120 hr., but no quarantine is required.

Turkey reopened for passenger flights in June and with one exception is entertaining the most-liberal visitation policy of any country in Europe. That exception is Turkey’s long-time foe, Greek Cyprus, from which no flights can enter Turkish airspace. Passenger flights originating in any other country are welcome. And as long as passengers are not exhibiting COVID-19 symptoms, quarantines are not imposed; however, health checks will be administered on arrival. The Turkish Directorate General for Civil Aviation (DGCA) has published guidance for operators on preparation for flights to the Anatolian Peninsula on the DGCA internet site at http://web.shgm.gov.tr

Operating in European Airspace

The EBAA’s Kahn advises that once operators have educated themselves on the pandemic requirements for their destination countries, they file well in advance. “Make sure you have all the information available so Eurocontrol can manage the flow and the airports will know when you are coming in. Be aware of night curfews or evening or morning ‘shoulder curfews’ that might be imposed and limit your ability to get into airports at certain times. Do your homework. Most restrictions are noise-related, which is why there are so many curfews.”

The EBAA and airspace users “do not have a discussion in Europe about privatization of ATC, as business aviation does in the U.S. ,” Khan revealed. “What we do have here is a fight, not just by business aviation, for more efficient ATM in Europe, as there is a general inefficiency in the system. In that sense, we are together with our colleagues in the airlines. It is not Eurocontrol that is the problem, it is the national ANSPs. The patchwork we live with exists because of nationalism; Eurocontrol is trying to facilitate flow across the Continent.” These inefficiencies result in limited access to congested airports; all the large hubs are congested and, thus, slotted, which Khan believes is unfavorable to business operators.

But now, during the pandemic, a paradox has emerged: Due to the huge decrease in airline traffic, business operators have no problems getting into these airports “because there is no one else flying,” Kahn noted, and “the airports are glad to have that traffic!” But as operations return to normal levels, it is expected that business aviation will again have a hard time gaining access to those facilities. “The worst ones are Heathrow, Paris CDG, Frankfurt, Amsterdam and others,” Kahn continued. “Obviously, business aviation also flies regularly to regional airports that are less constrained, but most executive passengers want to fly to the hubs.” The congestion depends on seasonality for some airports, especially those in southern Europe, but at the major hubs, it is year-round.

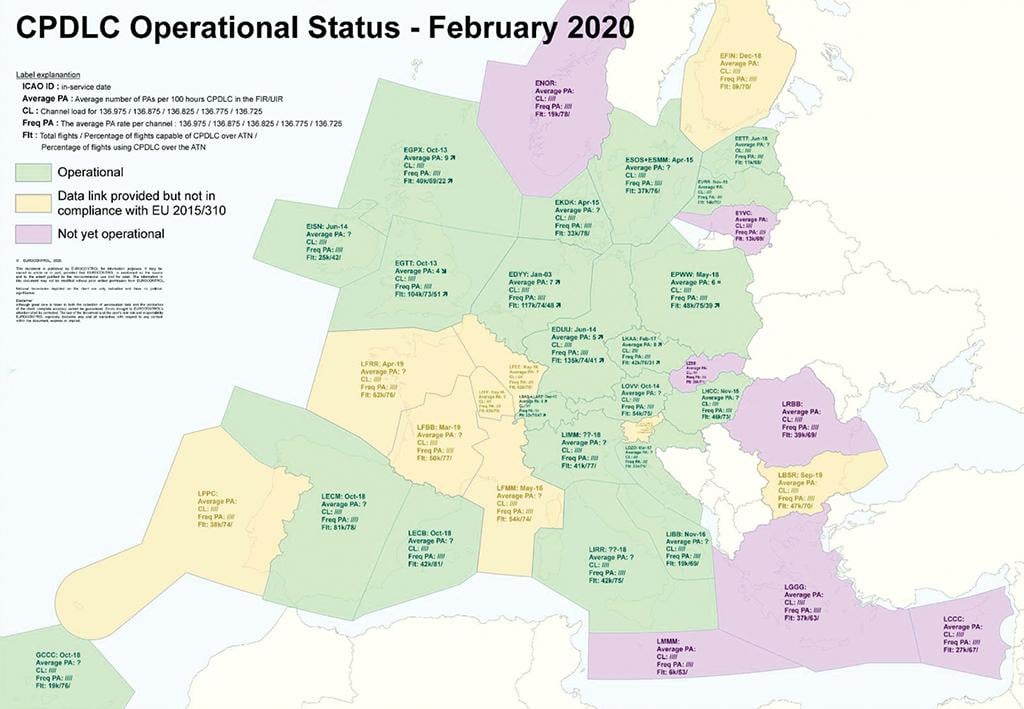

Early in the pandemic, a major mandate deadline came due that affects European air operations above FL 285. This is the requirement for the Aeronautical Telecommunications Network (or ATN B1), a VHF data-link system supporting Controller-Pilot Data Link Communications (CPDLC) in domestic (i.e., non-oceanic) airspace, the deadline for which became effective on Feb. 5, 2020, after being rescheduled several times since 2018.

In Europe, ATN has long been held out as one of the foundational pieces of the Single European Sky ATM Research (SESAR) modernization program (comparable to the FAA’s NextGen). At its most basic, ATN B1 is texting as an adjunct to (and eventually a replacement for) voice communications. The beauty of it — and right now a hopefully fixable disadvantage — is that it operates off of the existing cellphone tower grids supporting mobile telephones.

Get Ready for Data Link

Operators need be aware that now — with exceptions we’ll get to further on — aircraft expecting to cruise above FL 285 in Eurocontrol-managed airspace must be equipped with ATN B1 avionics and their crews trained to use it. It is also important to understand the difference between ATN, which operates CPDLC through a ground-based VHF telecommunications network, and FANS 1/A, the oceanic surveillance and comm data-link system that bounces its text messages off communications satellites in geostationary orbits 25,000 sm above the earth. This means that (again, with exceptions) if an airplane is equipped only with FANS avionics, it will not be able to access ATN B1, since the latter is not compatible with FANS and also uses a different messaging protocol. So equipage, especially in older business aviation airframes, could be an issue for some operators.

While the intentions behind domestic CPDLC might have been a good idea in the pre-COVID era when traffic was predicted to increase exponentially and data-link comm was seen as an efficiency expediter, establishing the ATN B1 network has been challenging in the patchwork of states that forms the EU. Even with the deadline in effect, the continuity of the system is inconsistent across the Union.

As Khan sees it, “We are experiencing a lot of implementation issues with the CPDLC mandate. The first deadline was 2018, but the system is still not fully deployed by the individual EU member nations, which is frustrating to operators that have equipped.”

As of this fall, the status of the 41 continental member-states of Eurocontrol fell into three categories: fully implemented, not implemented and not in compliance. According to Eurocontrol’s Thomas, at that time, 75.5% of airspace users were ATN B1-capable with 18% exempt (again, explained later). “The remaining 6.5% were not compliant according to flight plans,” Thomas said, “but a third would probably be exempt if they filled out the flight plan correctly. There are still some avionics issues, as it needs to be installed in the aircraft, so it’s an issue for business aviation.” The Eurocontrol center at Maastricht has become “really reliant” on ATN, Thomas claimed. “Thus, we are supporting the technology.”

But there have been technical issues with ATN B1. “Originally, it was carried on a single frequency,” Mitch Lanius of 30 West International Procedures noted. “It quickly became evident that multiple frequencies were needed, and EASA kept changing the tech standards.” That meant that anyone who equipped early did not meet the tech standard du jour. “Six FIRs have not turned it on; eight have but are not compliant technically. One problem with it is that it gets interference from adjacent frequencies that makes it drop messages.” Gribble added, “They are running out of bandwidth in the cell towers. Messages have a 60-sec. lifespan for replying; if not answered, the message aborts.”

Because of this, Lanius said, “The FAA abandoned it early as unsuitable.” In its design for NextGen, the FAA had considered a similar VHF-based domestic data-link comm network dubbed PM-CPDLC (for “protected mode”).

Now, for the aforementioned exceptions. First, aircraft equipped only with FANS 1/A avionics can use that equipment for data-link comm in U.K. airspace and when being worked by Eurocontrol’s Maastricht Center. “Anywhere else,” Gribble said, “it will be ATN B1 or nothing but voice.”

Second, for operators who have not equipped their aircraft with ATN B1, there is an exemption under Paragraph (d) of EU Commission Implementing Regulation EU2019/1170 for aircraft with 19 or fewer seats and MTOWs less than 100,000 lb. (45,359 kg). According to Lanius, “The only business aviation aircraft that should not comply for this exemption is the Gulfstream 650ER, which exceeds 100,000 lb. at takeoff.” And of course, business jetliners like the BBJ and A319CJ.

This is obviously a concession to business aviation, given that the exemption covers most aircraft types operated in this segment by corporations, wealthy individuals, state governments or charter companies. But the handwriting is on the wall (or implicit in the regulations) that eventually Eurocontrol and EASA are going to want everybody on the same page (including the ANSPs that have yet to implement their ATNs). This is to say, those capable of conducting data-link comm when in European airspace. So, operators with plans to use that on a frequent basis should consider equipping with ATN B1 avionics.

In the meantime, Eurocontrol’s Thomas advises that “an aircraft that wants to fly at or above FL 285 in the European airspace covered by the Data Link Service Implementing Rule should indicate in the flight plan either equipage capability — enter ‘J1’ in field 10a — or that the aircraft is exempted — ‘CPDLCX’ in field 18. Today, even if neither is indicated, the flight plan will not be rejected at Eurocontrol Network Manager-level; however, plans to introduce an enforcement of the rule are ‘well advanced.’”

(France), and Skyguide (Switzerland) — have instituted the “Logon List” (formerly the “White List”) identifying certain business aviation aircraft types and ATN B1 avionics configurations by serial numbers and production blocks that are prohibited from logging onto the CPDLC networks due to previous high rates of failure. (Whether this is a problem with the avionics sets or the ground networks is unclear.) Aircraft on the Logon List, if covered by the previously described exemptions, may still operate above FL 285 but will be restricted to communicating with ATC via VHF voice. For more information on the Logon List, readers are advised to consult https://ext.eurocontrol.inwt/WikiLink/index.php/Logon_List.

Now, understand, these are the aircraft that are equipped to operate in ATN B1 airspace but which mess up the CPDLC networks. Go figure . . . but, hey, it’s 2020.