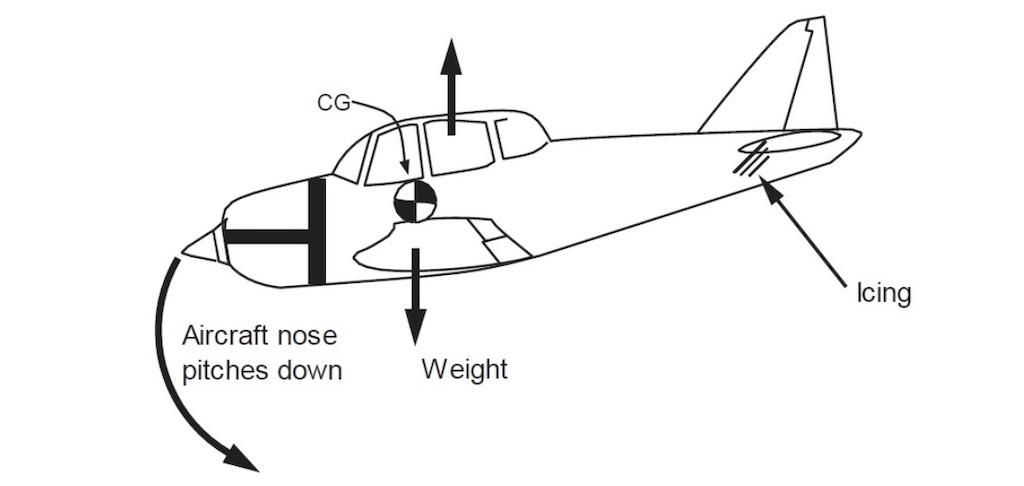

Pitchover due to tail stall as depicted in FAA Advisory Circular 91-74B

Do you give much thought to experiencing Ice Contaminated Tailplane Stall (ICTS) in your airplane? I didn’t think so. ICTS was a highly topical subject for pilots in the 1990s and 2000s but is not much discussed anymore. Still, uncertainty about the likelihood of an ICTS event remains.

A lot has been done to address the issue, but if you’re not an FAA official you may not have heard much about it. There’s some history and some good news.

ICTS was only one part of major concerns about aircraft structural icing that came about because of a series of icing-related accidents and incidents between 1997 and 2001. After an ATR-72 crashed near Chicago in icing conditions in 1994 and an Embraer EMB-120 crashed near Detroit in icing in 1997, the NTSB made aircraft icing a priority subject. “Airframe Structural Icing” was on its agency’s Most Wanted List from 1997-2002, and “Reduce Danger to Aircraft in Icing Conditions” was on the list from 2003-10.

Most of the airplanes involved were turboprops, but jets were not immune. They tended to be of the regional airline or business/corporate size. For example, an Air Canada Bombardier CRJ-100 crashed on an attempted go-around in 1997, with wing icing as a factor. Another EMB-120 was involved in a frightening loss of control incident near West Palm Beach, Florida, in 2001, and icing was found to be the culprit.

A result of all the emphasis on icing was a flurry of research by the FAA and other entities. NASA produced a couple of videos in 1998-99 on aircraft icing. They had great production values, the prestige of NASA and were widely viewed by pilots, often in recurrent training. I remember watching one of these videos, even though the big jets I was flying rarely experienced the kind of icing problems encountered by turboprop pilots. I thought it was good information, even if a little overwrought.

One subtopic of the videos had an effect far beyond the real scope of the potential problem: ICTS. Even though there were very few documented cases of crashes, ICTS seemed to be a very real problem. The video segment was fascinating and yet there was no real training for ICTS and no recovery procedure for it in flight manuals. Pilots were left with an uncertain and ambiguous impression. How would you know what type of stall you were experiencing—normal aerodynamic or tailplane? The recovery actions were opposite of one another.

The Colgan Air Flight 3407 accident on Feb. 12, 2009, brought home how misleading the training could be. The accident airplane—a DHC-8-400—was a twin-engine turboprop. Could it have been experiencing ICTS? The answer was clearly no. That airplane had been shown by its manufacturer to be immune from ICTS. But when those of us doing the investigation interviewed a cross-section of Colgan pilots, they all remembered vividly the ICTS part of the videos they had seen in training.

We wondered if the possibility of experiencing ICTS had been a subconscious influence on the accident pilots as they were trying to recover from the aerodynamic stall the captain himself had induced. Both pilots had seen one of the videos multiple times. Was it possible they were attempting a tailplane stall recovery? When we studied the airplane’s performance and auditioned the cockpit voice recorder, we concluded they were not.

Nonetheless, the videos were a problem. It turned out that for most airplanes, most of the time, the videos represented negative training. ICTS events are rare, very rare.

To address and eliminate confusion about ICTS, we wrote NTSB Safety Recommendation A-10-25: “Identify which airplanes operated under 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 121, 135 and 91K are susceptible to tailplane stalls and then (1) require operators of those airplanes to provide an appropriate airplane-specific tailplane stall recovery procedure in their training manuals and company procedures and (2) direct operators of those airplanes that are not susceptible to tailplane stalls to ensure that training and company guidance for the airplanes explicitly states this lack of susceptibility and contains no references to tailplane stall recovery procedures.”

The FAA was overwhelmed by the volume of work needed to respond to the Colgan safety recommendations and the accompanying laws passed by Congress and its response to the ICTS recommendation took time. The agency issued airworthiness directives on 10 airplanes about which the FAA had suspicions in 2010. It reviewed the entire subject by 2013 and identified airplanes susceptible to tailplane stalls. It directed POI inspectors to have their air carrier pilots stop watching the NASA video.

The FAA published Notice N8900.267, a focused review of ICTS training, in 2014. In 2016 the agency said that nearly all airplanes certified under Part 25 and most certified under Part 23 had been evaluated and found to be not susceptible. Some other types had made design changes or changes to procedures and limitations to prevent tailplane stall. Flown within their certified envelope, these airplanes are not going to experience a tail stall.

The NTSB was satisfied and closed out its recommendation as having had acceptable action in 2016.

A big question remained. Working pilots wanted to know what airplanes remained out there that were susceptible to ICTS. The FAA was mum for a long time, but now there’s list of airplanes that are not susceptible to ICTS and which should not have training for the condition.

- That list can be found at: https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/aircraft/air_cert/design_approv…. It’s a very long list and includes most of the types formerly suspected of being vulnerable.

- In addition, FAA produced a new video, CRC-508, “Ice Contaminated Stall” in 2016, that is worth a watch: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NBX84bF2d4U

- Finally, for those who want in-depth knowledge about aircraft icing, read FAA Advisory Circular 91-74B, “Pilot Guide to Flight in Icing Conditions.” There are two small sections devoted to ICTS. https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/advisory_circulars/index.cfm/g…

Comments

I have personally experienced full tail stall in two different types of airplanes, although in neither case was icing a factor. These were flight test scenarios. And, no, I do not like them!

As an American Eagle captain at the time of the crash of flight 4184,

we were extensively briefed about tail ice, even though 4184 was not tail icing. Interestingly, my tail stall in the Twin Otter did lead to an amazingly simple modification, completely removing the issue. A horizontal strake was added ahead of the stabilizer root.

Ian Hollingsworth

DER Flight Test Pilot

(Flight Technology Corporation)