Simulated image of the DHC-2 Beaver 1.3 sec. before midair collision.

When another pilot’s error causes an accident that involves you and he is clearly at fault, does that relieve you of any responsibility for the accident? Legally, maybe yes, but from a safety perspective the question that must be asked is “did you do everything you reasonably could to anticipate and prevent the accident?” An accident that took place in Alaska is a case in point.

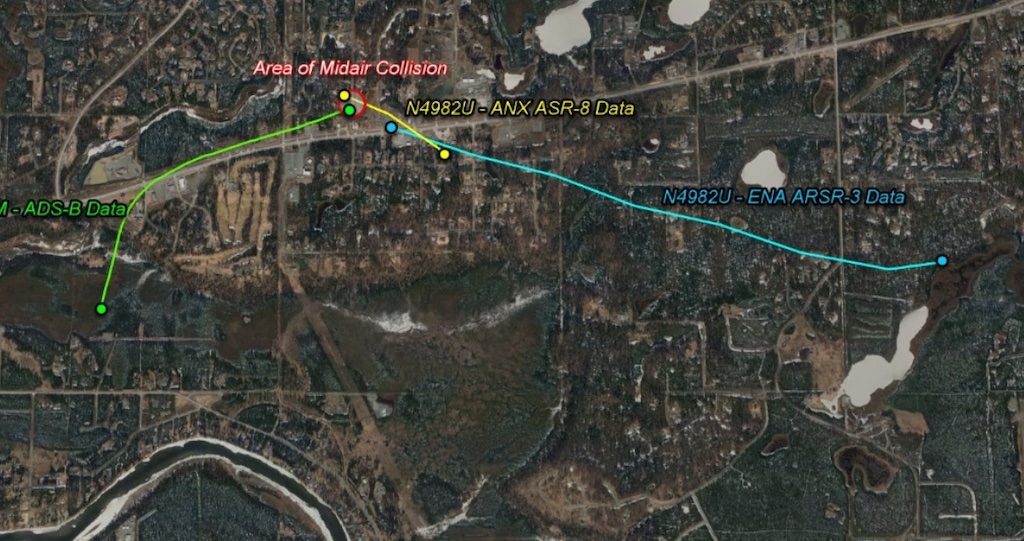

A float-equipped de Havilland DHC-2 Beaver was struck by a Piper PA-12 Super Cruiser over the town of Soldotna, Alaska, on July 31, 2020. The Beaver was a Part 135 charter flight carrying five passengers. The Piper pilot was alone. Both airplanes plummeted to the ground and everyone aboard died. Notably, the pilot of the Piper had no FAA medical certificate because his vision was too poor to pass the vision exam.

FAA records showed the PA-12 pilot was denied medical certification eight years before the accident because of open-angle glaucoma with visual field loss in both eyes. He apparently didn’t think his vision was that bad because he appealed the denial. His appeal was rejected by the FAA. When the NTSB’s medical officer reviewed the pilot’s records, she found that his glaucoma was severe and had caused irreversible optic nerve damage and visual field defects in both eyes.

The Beaver pilot’s brother, who was also a pilot for the charter company, told the NTSB: “the sole cause of this accident is due to the total disregard of the pilot of the PA-12, who had been denied a medical certificate due to vision problems, which prohibits you from piloting an aircraft. Had he not been piloting the aircraft, the accident would never have happened.”

Adding to the PA-12 pilot’s culpability was the fact that he had made major modifications to his airplane without FAA approval, and the experimental registration he applied to the airplane’s tail was not valid. He was an Alaska state representative and should have known better.

While the Piper pilot was clearly at fault, there’s more to the story.

ADS-B In And Out

The Beaver was not equipped with either ADS-B In or Out. It was equipped with a Garmin GTX327 transponder that can only provide Mode A and C transmissions. Because the airplane only operated in Alaska Class E and G airspace, this installation complied with 14 CFR 91.225, the regulation that pertains to ADS-B equipage.

The Piper pilot had made modifications to the PA-12 that could have helped prevent the accident. He installed a non-certified version of a Garmin G3X Touch system along with a GDU460 display system that received data from multiple avionics units, including a GTX23ES Mode S transponder and a GDL39R ADS-B In receiver. The NTSB found that the Piper was transmitting an ADS-B Out signal and would have been a “client” for ADS-B In.

ATC radar did receive nine UAT uplinks from the Beaver’s transponder, and the Piper could have received its broadcast data. The NTSB couldn’t determine if the Piper actually received the UAT signals, but what’s certain is that without ADS-B, the Beaver pilot had no chance of receiving an electronic traffic alert about the Piper.

Had the Beaver been equipped with ADS-B In and Out, the NTSB said, the collision would almost certainly have been avoided.

The NTSB has long recognized the limitations of the “see and avoid” concept of collision avoidance, even for pilots with perfect eyesight. An agency specialist created a cockpit visibility simulation of the Soldotna collision that shows how difficult it would have been for the two pilots to see one another.

After a midair collision in Ketchikan, Alaska, in 2019, the NTSB issued recommendation A-21-17 to the FAA concerning ADS-B. It called on the FAA to require the installation of ADS-B Out- and In-supported airborne traffic advisory systems that include aural and visual alerting functions in all aircraft conducting operations under 14 CFR Part 135.

When investigators spoke with the FAA principal operations inspector (POI) for the Beaver Part 135 certificate, he said he was a big advocate of ADS-B In and Out “to electronically identify aircraft that might be in close proximity and might be a danger.” He brought this up with the accident pilot in 2019 and again in July 2020, the month of the accident. The pilot had said both times, “well, yeah, we're thinking about it, but it's expensive.” The POI’s reply was “yes, I know ADS-B is expensive, but if you can prevent one mid-air that’s your own, it’s priceless.”

For small commercial operators, the cost of an ADS-B installation is a legitimate concern. Overcoming that objection should be a priority, and maybe the FAA or one of the industry alphabet groups could help. I’m thinking about a publicity program, subsidized loans and more price competition as ways to encourage universal ADS-B equipage.

The Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) provides guidance about costs of ADS-B equipment. According to AOPA’s information, Mode S (1090 MHz) transponders range in cost from $2,495 to $7,995; 978 MHz UAT transceivers cost from $2,095 to $5,143. The cost of ADS-B In equipment ranges from $549 to $2,995. None of these charges include installation.

The following link provides the details. Scroll down to ADS-B Product Lists. https://www.aopa.org/go-fly/aircraft-and-ownership/ads-b

Having as many as possible ADS-B-equipped aircraft benefits everybody, because we all need to see one another electronically. Once a collision occurs, whose fault it is no longer matters to the victims.

The FAA is considering the NTSB’s ADS-B recommendation and may decide to initiate a rulemaking to mandate the technology’s installation on all Part 135 aircraft. Wouldn’t it be best if all Part 135 operators decided to voluntarily equip themselves with ADS-B In and Out? Yes, it’s expensive, but it would make them safer, possibly lower their insurance costs and make another FAA rule unnecessary.