Airspeed indicators don’t fail very often, but when they do pilots often have difficulty recognizing the problem and maintaining control of the airplane. A Boeing 717 crew barely survived a loss of airspeed indication in 2005, and an Air France Airbus A330 was lost in 2009 when the crew failed to understand what was happening when they lost their airspeed indication. Both flights experienced pitot tube icing.

A highly experienced Air Force fighter pilot lost control of his recently acquired Cessna 421B in 2019 while flying in icing conditions. The NTSB found pitot probe icing was the cause of the loss of control and the subsequent crash. Most of the pilot’s experience was in flying modern automated airplanes. When he bought the 421, he was going backward on the airplane design evolutionary scale, and it appears he was not prepared for either pitot icing or flying without an airspeed indictor.

The accident took place on the late afternoon of March 17, 2019. The departure point was Dayton International Airport (DAY), in Dayton, Ohio; the destination was Delaware Municipal Airport (DLZ) in Delaware, Ohio, which was only about 55 nm to the northeast. After obtaining an IFR clearance from clearance delivery at 1707 EDT, the pilot taxied to runway 24L and took off at 1715. He turned north and contacted Columbus Approach Middletown Radar, who told him to maintain 3000 ft and cleared him to turn right on course.

According to the air traffic control (ATC) chronological summary, Middletown Radar broadcast a center weather advisory for the Columbus and Dayton areas at 1725. The contents of that advisory were not given in the accident report, but an Area Forecast Discussion (AFD) current for the area at the time said there was a surface low pressure area moving east and snow showers could be expected. Ceilings at nearby airports were bobbing up and down between 400 ft and 1600 ft, and temperature-dew point spreads were running around 1-to-2 degrees.

The pilot checked in with Columbus North Radar at 1729, level at 3000 ft. The controller advised him of an area of snow just ahead and assigned him a 15-degree right turn. At 1735 the controller noticed the airplane had descended 300 ft and assigned a further right turn to 090 degrees. One minute later the controller noticed the airplane was at 3300 ft and asked if he was “doing all right there?”

The pilot replied he was “picking up some icing” and needed to “pick up speed.” He requested and received clearance to descend to 2500 ft, where he found he was still in the clouds. The controller then noticed the airplane was in a climb. After confirming this with the pilot, he cleared the flight to maintain 6000 ft and said he could level at any altitude he liked. There was no traffic in the area.

At 1739 the controller issued a low altitude alert to the pilot and asked if he could be of any assistance. A minute later the controller lost the altitude signal on the airplane and asked for a radio check from the pilot. There was no reply.

The airplane struck a field about 7 mi. southwest of the DLZ airport. The pilot did not survive.

The Investigation

The NTSB’s investigator in charge traveled to the accident site. He was assisted by representatives from Textron, Continental Engines, Avidyne and the FAA. He found the airplane wreckage was highly fragmented along its 850-ft. ground path. Based on ground impact scars and wreckage, the airplane was in a left-wing low attitude when it struck the ground.

After crossing a two-lane road, the airplane struck two wooden utility poles. The engines were separated from the wings and heavily damaged. Investigators were able determine that each engine’s fuel system, pumps, nozzles and screens were in normal condition, and that spark plugs showed normal wear.

With such severe damage to the airframe, it was hard to establish any pre-existing anomalies or damage, and none were found. The pitot and static systems were too damaged to evaluate.

Remnants of two avionics devices were recovered. An Aspen EFD1000 Pro primary flight display was examined by a Vehicle Recorder specialist, but no data was recovered. The device had no non-volatile memory chips to record flight parameters, so there was no stored historical data.

A performance specialist had better luck with an Avidyne integrated flight display (IFD). That device recorded navigation information, fuel flow and quantity, latitude, longitude and altitude. It also recorded the airplane’s airspeed and system annunciations and warnings.

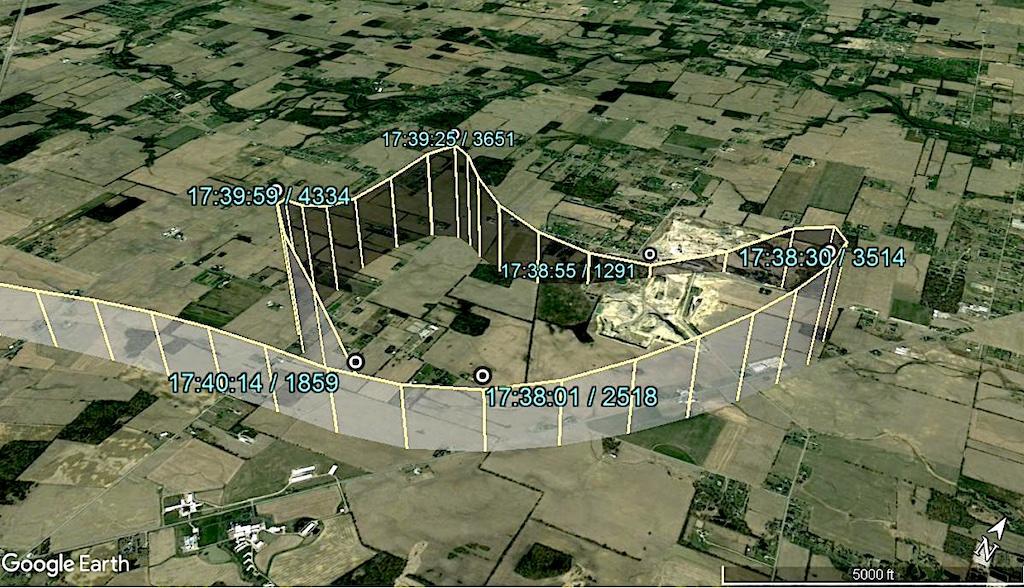

Given that the Cessna 421 did not have, and was not required to have, crash-hardened recorders, the Avidyne memory provided highly useful information. The specialist was able to integrate ATC radio transmissions and weather data from the meteorologists’ report to create graphs and graphics showing the details of the flight path.

The safety board meteorologist obtained what was termed a High-Resolution Rapid Refresh model sounding for the accident site at the accident site at 1800. It showed the freezing level was about 1400 ft. above the surface, with the potential for moderate clear ice between 1400 ft. and 2500 ft. The Current Icing Potential (CIP) product showed a 50% or greater probability of icing at 3000 ft.

For the first 17 min. of flight, the airspeed and groundspeed closely matched, with the groundspeed being about 10 kt higher. Then, right about the time the controller reported snow ahead, the indicated airspeed began to fall. In response to the declining airspeed indication, the pilot added power, with fuel flow increasing to about 60 gal/hr.

As the groundspeed increased jaggedly from around 150 kt to 190 kt, the indicated airspeed continued to fall, reaching zero at 1738. From this point on, the airplane was in a left turn.

Following the pilot’s descent to 2500 ft., he added a significant amount of power, and a series of three major altitude excursions followed, After a rapid climb to 3500 ft., he pulled power off and fell into a sharp dive, recovering just a few hundred feet above the ground. The first of three “sink rate, pull up, pull up” warnings was recorded by the Avidyne memory.

A second power increase and a second steep climb was followed by another descent and a third climb. The last climb peaked at 4334 ft. Ground speed at that point was less than 70 kt. The charted groundspeed at the end of the flight approached 250 kt.

The airplane, registration N424TW, was built in 1974 and was registered to a company in Bakersfield, California, in January, 2018. It was certified for flight in icing conditions. An annual inspection completed just a month before the accident showed total flight time on the airplane as 8,339 hours. The inspection record was thorough and showed no major mechanical concerns.

Investigators obtained a clear cockpit photo of the airplane in flight on an undisclosed date. The photo showed the Aspen display, two Avidyne flight displays and an S-Tec Fifty-Five X autopilot.

A portion of the C-421 Aircraft Flight Manual showed there was a procedure for obstruction or icing of a static source, but no guidance for pitot probe icing.

Pilot Background

The accident pilot was a 44-year-old retired Air Force lieutenant colonel. He was a distinguished graduate of the U.S. Air Force Academy with degrees in mechanical engineering and engineering sciences and a master’s degree in business administration. After attending the Naval Test Pilot school at Patuxent River, Maryland, in 2006, he flew the F-16 in combat and became an instructor in that airplane. He was a wing safety officer and squadron commander and became an F-35 evaluator pilot. He was reported to be the first pilot to log 500 hours in the F-35.

Following his Air Force career, he became chief pilot for Phoenix Flight Test in August 2018. That date coincided with his initial training and first flight in his C-421. He logged 15.9 hours of dual instruction in the airplane in early August 2018 and received a certificate of training on September 10 that year.

The pilot flew the C-421 a total of 46.4 hours before the accident, 8.3 of which was in actual instrument conditions. All of his time in the airplane was logged in August and September of 2018 except for 3.4 hr. flown in February 2019. He also logged 5.1 hr. in an Aero Vodochody L39C aerobatic airplane owned by Fantasy Fighters of Santa Fe, New Mexico, in late August 2018.

Federal regulation 14 CFR 61.57 (c) (1) requires a pilot to fly six instrument approaches within the six calendar months prior to flying in instrument conditions. The pilot was in his sixth month at the time of the accident and had only logged one instrument approach during that time.

Investigators found the pilot’s C-421 formal training record. Subjects covered during the training included adverse weather avoidance, ice protection systems and emergency procedures. They did not interview the flight instructors who conducted the training to find out if they discussed use of pitot heat or loss of airspeed indication.

Next: A Flight With Unreliable Airspeed Part 2, Comments and conclusions.