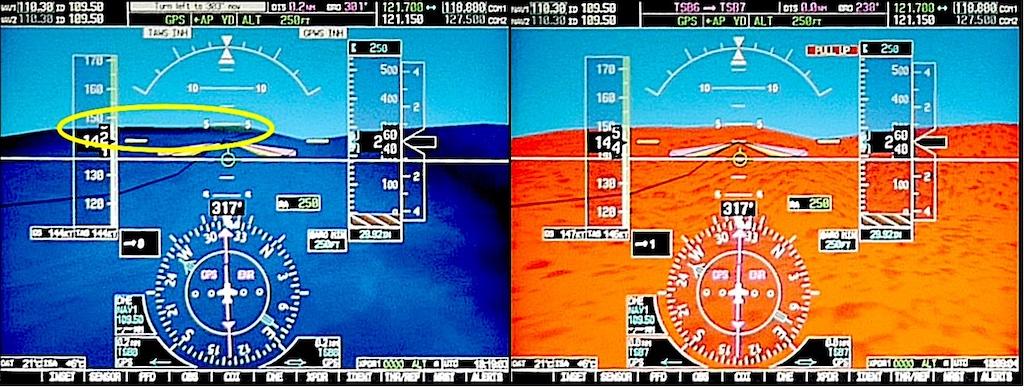

The flight simulation primary flight display terrain display.

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) classified the July 2019 crash of a Cessna 208 Caravan on Addenbroke Island, British Columbia, as a class 2 occurrence and conducted a complex investigation of the accident, including an in-depth analysis.

When investigators examined the wreckage, they found the Caravan’s wings and floats had been shorn off but came to rest nearby. The engine remained in place and the propeller remained attached to the engine, although the blades were damaged. The airplane was equipped with two Garmin 1000 primary flight displays (PFD) and a multifunction display (MFD); the left PFD and the MFD were heavily damaged. The processing units were recovered and later analyzed.

The airplane was not equipped with either a cockpit voice recorder (CVR) or a flight data recorder (FDR). However, there were three systems that recorded flight data: a Latitude Technologies S100 transceiver; the engine’s Air Data Acquisition System-digital (ADAS-d); and the Garmin 1000 avionics suite. The S100 unit recorded five flight parameters: time, position, ground speed, heading and altitude. The ADAS-d unit recorded 17 engine and flight parameters. The G1000 recorded 45 flight parameters, but the SD card needed to store the information was not installed, and most of the flight’s information was lost.

The Latitude Technologies S100 unit enabled near real-time aircraft tracking, sending out flight data every three min. Seair Seaplanes staff could track the flight’s progress and receive coded messages to the company’s flight follower. The aircraft’s icon turned purple after the accident, indicating to staff that the airplane was overdue for an update. No coded messages were sent by the pilot in the two min. immediately before the accident. Seair provided investigators with the flight data that was transmitted every three min. throughout the flight.

The S100 enabled pilots to view the routes of other Seair flights using a web application. Once in flight, pilots could obtain information from other Seair pilots, cell phone calls, texts and internet weather updates.

The ADAS-d unit contained five consecutive days of flight and engine parameters. No faults were found. On the accident flight, there were no changes to engine power or propeller speed for the last seven min. before the accident.

Single-Pilot Operation

The airplane was certified for operation by a single pilot. The controls for the second pilot were removed to allow seating for a passenger in the right seat. The airplane was manufactured in 2008 and had accumulated 4,576.8 hours. It was powered by a Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-114A turboprop engine.

The Caravan also was equipped with a Garmin GFC 700—a fully integrated digital automatic flight control system (AFCS), which included a flight director and autopilot. On the Caravan, it was certified for use at a minimum enroute altitude of 800 ft AGL and 200 ft AGL for instrument approaches. After examining the flight data, investigators concluded the autopilot had remained on throughout the entire flight after departure.

The airplane was about 400 lb. overweight for takeoff. The pilot’s flight plan showed fuel would be 900 lb., but it was actually 1200 lb. At least 320 lb. of passenger baggage and freight were also loaded aboard.

The pilot of the accident airplane had been a seasonal employee of Seair for 18 years. He had logged 8,500 total flight hours, and since qualifying on the C-208 in 2017, had logged 504.7 hours on that type. He held a Canadian commercial pilot license with appropriate ratings and had completed his last competency check about two months before the accident. He had an instrument rating, issued in 1998, but was not current. In any event, Seair was only authorized by Transport Canada for day VFR flight.

While most Seair Caravan pilots received full flight simulation training from an outside vendor, the accident pilot only received in-house training. His last competency check was signed by the chief pilot after a flight in the airplane. The simulator training the pilot missed focused on weather scenarios and low-altitude emergencies.

As a seasonal pilot, the accident pilot was only employed at Seair from May to October each year. He normally worked on Friday, Saturday and Sunday, with occasional duty on Thursday. In the two months before the accident, the pilot was on duty an average of 32 hours per week, In addition, he had a full-time, year-round job.

The accident pilot was a station attendant (commonly called a ramp serviceman in the U.S.) for an airline at Vancouver International Airport and had been employed there since 1996. He worked on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and occasionally on Thursday at that job. Investigators found he had averaged 42.4 hr. per week as a station attendant in the two months before the accident.

Overall, in the two jobs, the pilot had worked an average of 76.7 hr. per week in the two months before the accident, and he had worked 83.5 hours in the previous seven days. He had worked 27 out of the last 28 days, and his last day off was 15 days before the accident. In addition, he resided in a recreational vehicle parked at the airport near the runway. Cell phone records showed that he frequently received calls late at night. The pilot had just one five-hour window for sleep in between two 14-hr. shifts in the three days before the accident.

The Caravan’s Garmin G1000 avionics system included both a terrain awareness feature and a traffic advisory system. The system’s “Terrain-SVS” (Synthetic Vision System) is not a true Terrain Awareness System (TAWS) because it does not comply with the TSO-C151b certification standard. It does provide a forward-looking terrain avoidance (FLTA) feature that compares the aircraft’s projected flight path with known terrain features in the database and can issue caution or warning alerts.

The PFD and MFD display a terrain conflict that is 100 to 1,000 ft. below the airplane’s altitude in yellow; terrain conflict above that level in red. Garmin warns in its pilot’s guide that “the terrain avoidance feature is NOT intended to be used as primary reference for terrain avoidance and does not relieve the pilot from the responsibility of being aware of surroundings during flight.”

The pilot guide also describes a reduced required terrain clearance (RTC) alert feature. For level flight more than 23 nm from a runway, the RTC alert value is 700 ft. Flying at altitudes less than the RTC value will cause the system to continuously issue alerts. To avoid continuous alerts when flying below the RTC, the FLTA can be inhibited.

When the FLTA feature is inhibited, all visual and aural warnings are prevented. Seair gave pilots no guidance in its manuals or procedures about when to inhibit the FLTA, but investigators found it was routine for Seair pilots to manually inhibit the FLTA before takeoff.

Investigators concluded that the FLTA was inhibited during the accident flight.

To determine what the pilot would have seen on his displays, investigators flew a full-flight simulator equipped with a G1000 suite similar to that of the accident airplane. The simulator was loaded with the Caravan’s flight path. When flown above 700 feet AGL, the FLTA provided an initial caution message when the aircraft was approximately 1.2 nm, or 30 sec., from the Addenbroke Island shoreline The message changed to a warning when the aircraft was 0.75 nm, or 19 sec., from the shoreline.

When flown at the altitudes the Caravan actually flew, the system produced continuous alerts. With the FLTA inhibited, the Addenbroke Island landmass barely protruded above the display horizon and its color blended with ocean. With the FLTA activated, the terrain was displayed in solid red.

In Part 3, we describe weather and geographic features of British Columbia’s central coast.

Too Low: A Cessna Caravan Crashes Into Terrain, Part 1: https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation/safety-ops-regulation/too-lo…