Markups for OEM parts, rising energy costs and labor expenses are all contributing to inflationary pressures on European MRO providers.

When inflation spiked in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, it was a nasty shock for a generation of Eurozone consumers and businesses used to annual price rises of less than 2.5% for almost all of the previous 25 years. A similar story played out in the UK, where inflation peaked at more than 11% late in 2022, after a quarter-century near the 2.5% mark.

Accompanying this shift was the end of more than a decade of cheap credit, during which businesses and home-buyers had enjoyed near-zero interest rates. The effects of both changes are still playing out in the aviation aftermarket, and while inflation has come down from its 2022 peak, maintenance providers remain challenged by higher prices across their cost bases.

“Absolutely everything we touch has seen varying degrees of cost increases, many of which are double-digit,” says Ian Jones, head of sales at UK-based Storm Aviation, a provider of line maintenance and other aviation services.

In Germany, the same is true for MTU Aero Engines. “As is the case across the industry, we are experiencing high inflation across the board,” says Wibke Eichhorn, senior vice president for commercial MRO at the OEM and maintenance provider.

Cost Increases

At the tail end of the pandemic, global supply chains fell under severe strain as demand picked up and encountered shortages of labor, materials and logistics capacity. The problem was particularly acute for aviation, one of the worst-hit industries during the pandemic and which had lost numerous skilled staff and engineers to other sectors. These problems were then exacerbated by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, which led to a spike in energy prices.

While airlines and maintenance companies were somewhat used to price rises, notably the annual above-inflation markups for OEM parts, they soon found that costs were rising in other areas as well.

“Most parts of the business have been under inflationary pressures,” says Greg Macleod, managing director of London Stansted-based GT Engine Services, an engine MRO provider.

One big increase that had not occurred for many years in the aftermarket was energy costs, prompting some maintenance providers to seek more sustainable solutions to power their facilities—particularly in Germany, where many industries had previously enjoyed years of cheap Russian gas.

“Energy, especially at our German locations, is one of the drivers for cost increases,” Eichhorn notes. “MTU is counteracting that by investing in self-sustainable energy infrastructure such as photovoltaic technology and dual-use heat pumps.”

Macleod also recognizes the significant challenge of energy price inflation. “One of our biggest factors is energy costs, and overnight without warning our energy supplier doubled our prices,” he recounts. “Thankfully, we had just installed solar, which mitigates the rise somewhat.”

Labor expenses also have grown sharply, given the need to retain skilled personnel and to protect employees against consumer inflation. Macleod notes that this combination of factors led to wages rising even faster than inflation as the aftermarket sought to restore capacity as quickly as possible to meet resurgent demand for flights.

“We still have a huge skill shortfall in the industry, so we try to keep wages attractive, staying competitive,“ he says. “We also have to look after all of our existing staff and dampen the effect on their rising household bills. The net result has seen our wages outstripping inflation.”

Storm Aviation’s Jones agrees, noting that MRO providers have to be increasingly creative to retain and attract staff.

“To remain competitive in a market where some of the biggest airlines are offering sizable package increases to tempt maintenance staff away from MROs, we must listen to our colleagues, reward hard work, pay commensurate salaries and be inventive with other workplace benefits,” including health care and dental coverage, he says.

There also have been major price increases for third-party services and for materials, “especially consumables,” Macleod says, adding that “consumable prices are the hardest to pass on.”

MTU’s Eichhorn sees services and materials cost increases reflecting broader inflationary trends, as well as aviation’s specific supply chain challenges in the wake of COVID-19. “Naturally, the share of material cost represents a major portion of our maintenance services and is therefore a significant driver for the overall cost increase,” she adds.

Mitigating Inflation

If their finances allowed, some MRO providers and airlines sought to preempt higher-than-usual price hikes for parts by buying stock before catalog prices were changed in 2022, when inflation took off.

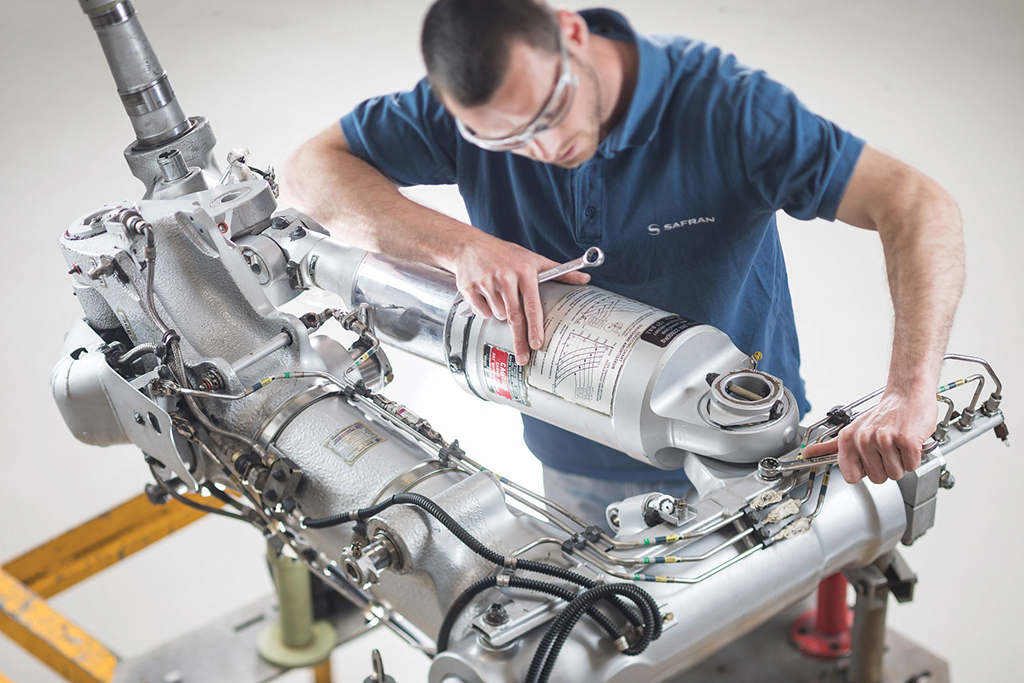

Asked in mid-2022 whether inflationary trends had influenced spare parts pre-buying by Safran’s customers, CEO Olivier Andries agreed there had been an impact. “We will soon communicate on our catalog price increase that is planned for November of this year [2022],” he said. “But you can expect it’s going to be up compared to what we have basically done in previous years, considering the inflation.”

Andries also noted that it is easier for Safran, which acts as both an OEM and a maintenance shop, to pass on inflationary costs to customers through time-and-materials contracts than through flight-hour-based support agreements.

Given airlines’ urgent need to restore capacity over the past 18 months, one might expect them to be somewhat insensitive to maintenance cost increases, but MRO providers say their ability to pass on inflation-related increases is constrained.

“In our experience, airlines remain razor-focused on securing the best pricing and terms,” Jones says. “But the truth is that many operators now have to pay more for maintenance support, certainly in the line maintenance environment.”

“Most customers accept that the costs have to be passed on and have been very accepting of the situation,” says Macleod at GT Engine Services. “By the nature of their business, we do have some low-cost carriers that struggle with the concept of any type of increase.”

Eichhorn points out that MTU’s ability to pass on costs depends on the type of contract it has with customers, although it will not always do so. “Even if contracting terms allow us to pass on cost increases, this is not the overall goal as customers are always looking to manage cost, and in turn, so do we,” he says.

One way to control costs is to use used serviceable material, parts manufacturer authority parts and designated engineering representative repairs instead of new parts.

“At MTU Maintenance, all the departments directly involved with MRO operations—especially engineering and procurement—work together to design the repair or overhaul of an engine in a way to optimize the costs of a shop visit in accordance with customer needs,” Eichhorn explains.

She also emphasizes that airlines remain sensitive to maintenance cost increases as they continue to recover from the financial strain of the pandemic. “Price is the No. 1 factor with respect to engine MRO decisions and provider selection. Engine maintenance cost represents a big portion of the overall maintenance costs at airlines,” Eichhorn adds.

Other Economic Pressures

Accompanying higher inflation have been steadily rising interest rates from central banks in Europe and the U.S. Maintenance providers are less exposed to these fluctuations than finance-focused areas of the aftermarket such as aircraft leasing, although they still face higher debt costs. Some MRO providers also incorporate asset finance—including engine leasing—in their business model.

“Asset finance is not economical now, with interest rates where they are, so we have changed policy and now self-finance even the largest purchases,” says Macleod, who also highlights a rise in insurance costs.

Meanwhile, general supply chain tightness endures, impacting procurement and turnaround times, with MTU estimating that overall engine MRO capacity will remain under strain for up to two more years.

At Storm Aviation in the UK, Jones says the company faces slower lead times, as well as clients that have issues importing aircraft and spare parts. “This is time-consuming and costly for them and can have a negative impact when we bid against MROs in mainland Europe,” he says.

Then there is the fallout from Russia’s war on Ukraine and the resulting sanctions, which have affected many European MRO providers with exposure to the country.

For example, prior to the war, about 400 aircraft in Russia had some form of support contract with Lufthansa Technik, with many served via Lufthansa Technik Vostok, its 100%-owned Russian subsidiary.

Elsewhere in the aftermarket, Rolls-Royce stopped providing Aeroflot with engines, spares and maintenance services. It said Russia accounted for 2% of its global revenues. French company Safran, meanwhile, noted near the start of the war that the crisis would strain global titanium supplies for aircraft and engine production, for which Russia was its main supplier, and that it had begun to stockpile titanium.

MTU was also affected, recognizing impairment charges of €59 million ($62.2 million) in connection with the war in Ukraine.

“This affected the stake in the PW1400G-JM program, which was intended for the Russian Irkut MC-21 and has been permanently written down as a consequence of the Russia-Ukraine war and, to a smaller extent, assets related to the stake in the consortium for the PW1100G-JM aftermarket business and MTU’s commercial MRO business,” Eichhorn says.