Another month and another new-space company announces a major change to its business plan. But are all the strategic overhauls a sign of the inevitable collapse—once again—of space entrepreneurship, or is it a necessary recalibration on the path to a new economy, even if it is one of many to come?

It is easy to assume the first rather than the second. With each announcement from a space company that became publicly traded in recent years as part of the special-purpose acquisition company wave, SPAC becomes a quartet of scarlet letters. After all, none of the business plan changes were forecast when these companies were marketing their vision to public investors just a year or two ago.

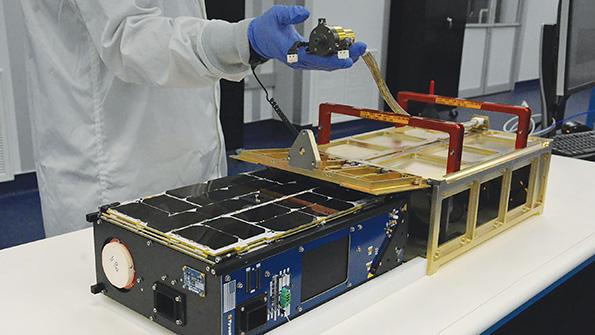

Yet individually, many of the business plan adjustments are understandable. Take small-satellite-maker Terran Orbital, which on Oct. 31 formally announced an alignment with Lockheed Martin, receiving a $100 million investment boost and signing a three-year strategic cooperation agreement. The SPAC startup also is focusing manufacturing in Irvine, California, instead of a highly-touted buildup on Florida’s Space Coast. It also ditched once-core plans for lofting a constellation of satellites sporting synthetic aperture radar.

Before its reverse merger with a SPAC, Terran said it was one of the last nonaligned providers of new-space, small-satellite manufacturing and Earth-observation (EO) services. It would make satellites for anyone; EO would be its own proprietary offering, as it was seen as a booming market.

Still, Terran has taken Lockheed venture capital since 2017 and was identified by the defense prime’s leaders as the kind of strategic investment for which they increasingly were looking rather than large-scale mergers and acquisitions. Terran is a Lockheed supplier on Tranche 0 and Tranche 1 under the U.S. Space Development Agency’s Transport Layer program for military data and communications connectivity. Those awards tripled Terran’s backlog since the end of 2021.

In February, Terran announced somewhat surprising plans to expand its manufacturing in Irvine by leasing a 60,000-ft.2 commercial facility next to its existing location there. At the time, the expansion was billed as adding to previously announced plans to construct the world’s largest “Industry 4.0” space-vehicle manufacturing facility on the Space Coast. But now Terran is pivoting its manufacturing base to Irvine.

Observers see the shift as huge but logical. “Given that various avenues of capital support have changed dramatically in the past year, management is refocusing on its satellite manufacturing business that has a proven track record and backlog,” Melius Research analysts said after the latest announcement. “The problem is that the current market environment is not willing to finance a satellite constellation with a multiyear payback.”

Of course, not all strategy shifts are embraced by the market, even if they seem logical. In August, rocket upstart Astra Space, another SPAC debutante, shelved its troubled small launch vehicle to focus on a larger launcher. It also unveiled a concerted push to sell spacecraft engines to other space companies.

But on Nov. 8 the company announced layoffs of 16% of its workforce and $119 million in write-downs of assets as it seeks a “financial runway” into 2024 amid a major business plan change. A newly appointed chief financial officer acknowledged there are concerns about the business. The company is at risk of being delisted from the Nasdaq stock exchange, as its share price remains under $1 after hitting a high of $15.47 in July 2021.

Will Astra make it? Perhaps, but it is focusing on rocket and space propulsion markets, which are getting crowded. Just in May, Astra leaders touted “space services” as the future cash-cow “North Star” for the company—but in the August overhaul, they shelved those plans. It is far more likely that Terran will survive through the combination with leading defense prime Lockheed and the underlying military programs.

Regardless, some of the new players who came of age in the recent explosion of new-space companies are likely to survive—either as standalone entities or as major units of others—if for no other reason than the demand-pull has changed. From supporting the U.S. Space Force to NASA’s commercialization of everything from rocket launch to space stations and lunar missions, outer space is changing from a domain occasionally entered by superpowers to one in which private industry is newly operating on an almost weekly basis.

No other domain has seen a reversal of fortune once it became a revenue-generator of its own. Space is no different in that sense, and some of the new companies—albeit not all—will move up in it.