The SLS put on a spectacular show for night owls gathered at the Kennedy Space Center’s Operations and Support Building II.

It has been more than a decade since NASA retired its space shuttle fleet and cast its eye on developing the Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft for human travel beyond low Earth orbit. Along the way, billions of dollars have been spent, hundreds of technical problems have been solved, and presidential administrations have come and gone.

In the still, predawn hours of Nov. 16, the first Space Launch System (SLS) rocket lifted off from Launch Complex 39B at the Kennedy Space Center, Florida, shattering the quiet of the night with a blinding light and thundering roar to become the most powerful rocket in operation today, surpassing SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy.

- Orion shakedown cruise is underway

- Splashdown is expected on Dec. 11

Two min. 11 sec. after launch, a pair of five-segment solid-rocket boosters, manufactured by Northrop Grumman, were jettisoned, leaving four RS-25 engines—built by Aerojet Rocketdyne and recycled from the space shuttle program—firing to deliver the rocket’s upper stage and attached Orion capsule into a preliminary orbit 104 mi. above Earth.

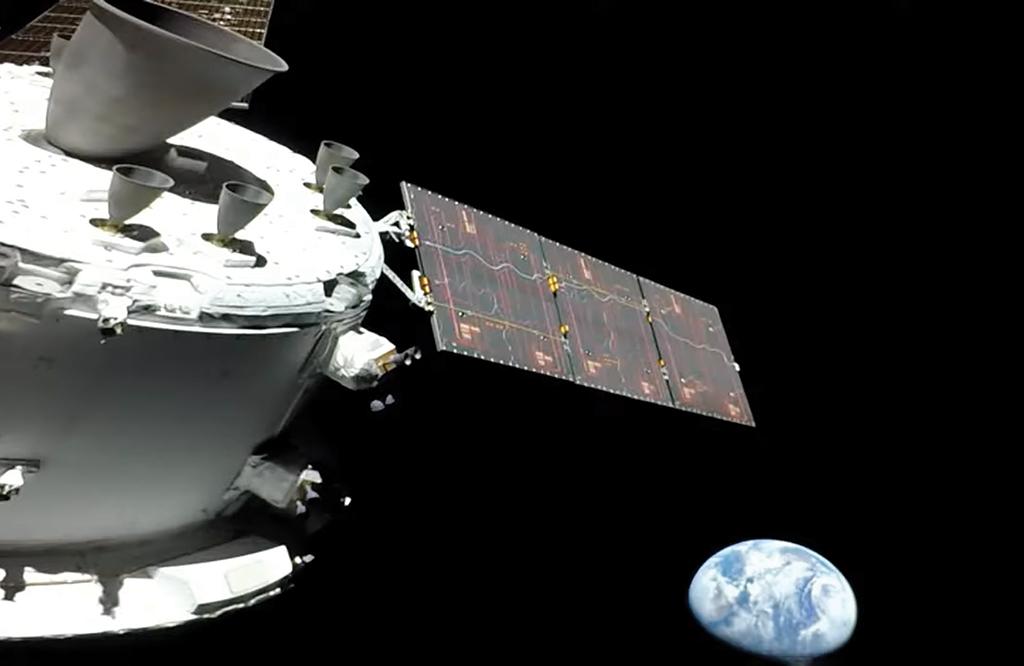

The upper stage, known as the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS), took over from there. First came a 22-sec. firing of the ICPS’ single Aerojet Rocketdyne RL10 engine to raise the perigee of Orion’s orbit. The spacecraft, built by Lockheed Martin, then deployed its solar arrays, setting the stage for a second ICPS burn that accelerated Orion to 25,600 mph—fast enough to escape the clutch of Earth’s gravity and reach the Moon. The 18-min. translunar injection burn was the longest ever conducted by an RL10, which has been operating for 60 years.

With Orion on its way to the Moon, the ICPS separated and then deployed 10 cubesats flying as secondary payloads. They include three lunar orbiters, a lunar lander, three radiation probes, an asteroid scout and technology demonstrations.

Orion was headed into a distant retrograde lunar orbit, which is planned to take it about 40,000 mi. beyond the Moon—and 240,000 mi. from Earth.

Packing 8.8 million lb. of thrust, the SLS is a two-stage expendable rocket that draws heavily from the predecessor space shuttle program. In its initial configuration, the SLS is designed to put 60,000 lb. on a trajectory to reach the Moon. Its lift capacity increases to 84,000 lb. to the Moon with the four-engine Exploration Upper Stage, currently in development. Boeing is the prime contractor for the SLS.

NASA tried three times in August and September to launch the SLS, which carries an uncrewed Orion spacecraft for a shakedown cruise ahead of a crewed flight. Two launch attempts were stymied by hydrogen leaks and other technical issues, while the last try was thwarted by the Category 4 Hurricane Ian.

The 322-ft.-tall SLS and Orion were returned to the launchpad on Nov. 4, only to face another hurricane. Category 1 Hurricane Nicole, which hit the Central Florida east coast on Nov. 10, peeling away some of the silicon-based insulation near the top of the Orion capsule, but NASA determined that the damage did not pose a flight risk.

In an attempt to preclude hydrogen leaks that bedeviled previous SLS launch attempts and tanking tests, NASA developed what it called a “kinder, gentler approach” to fueling by reducing the pressure in the liquid--hydrogen storage sphere to slow propellant flow.

Though tanking took an hour longer than previous attempts, the procedure worked flawlessly for filling the core stage tanks with 733,000 gal. of cryogenic liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen, which fed the RS-25s during their 8 min. 15 sec. of flight.

The launch team, headed by Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, then turned its attention to filling the ICPS tanks with 20,000 gal. of the same propellants. Preparations continued smoothly until about 9:30 p.m. EST on Nov. 15, when sensors detected a small leak in a hydrogen valve on the mobile launcher. Two technicians and a safety officer headed out to the launchpad to check connections and found loose bolts, which they tightened in an attempt to stem the leak. The repair was successful, and NASA resumed replenishing the core stage with liquid hydrogen.

As that issue was put to rest, safety officers with the U.S. Space Force’s Eastern Range reported a problem obtaining data from a radar tracking system due to a faulty ethernet switch. Replacing the switch took about 70 min., clearing the way for the countdown to resume. Launch occurred at 1:47 a.m. EST, 43 min. into the 2-hr. launch window. “There’s definitely relief that we’re underway,” Artemis I Mission Manager Mike Sarafin said at a post-launch news conference. “We’ve brought down a lot of risk today, but we’ve got a lot of mission ahead of us.”

The SLS’ successful debut set the stage for a 25-day flight test of Orion, which is designed to carry a crew of four into deep space for missions lasting up to 21 days. NASA is particularly interested in the performance of the spacecraft’s heat shield during its 25,000-mph return through Earth’s atmosphere, expected on Dec. 11. The Artemis I mission is slated to end with Orion’s splashdown in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of San Diego.

NASA plans to follow the uncrewed Artemis I with a crewed flight test on Artemis II in about two years. Beginning with Artemis III, NASA intends to land astronauts on the south pole of the Moon, kicking off a U.S.-led effort to open cislunar space for human exploration, research and commercial activity.

“It took a long time to get here, and we have a long ways to go,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson told reporters after launch. “This is just the test flight, and we are stressing it and testing it in ways that we will not do to a rocket that has a human crew on it. But that’s the purpose: to make it as safe as possible, as reliable as possible, for when our astronauts . . . go back to the Moon.”

Comments