Several companies plan to pursue electric, hybrid- and hydrogen-electric retrofits using MagniX EPUs.

With multiple aircraft modification and demonstration efforts underway, electric propulsion pioneer MagniX has its plate full. But the programs are complementary and focused on the company’s No. 1 priority: certification of its electric propulsion units, a senior executive says.

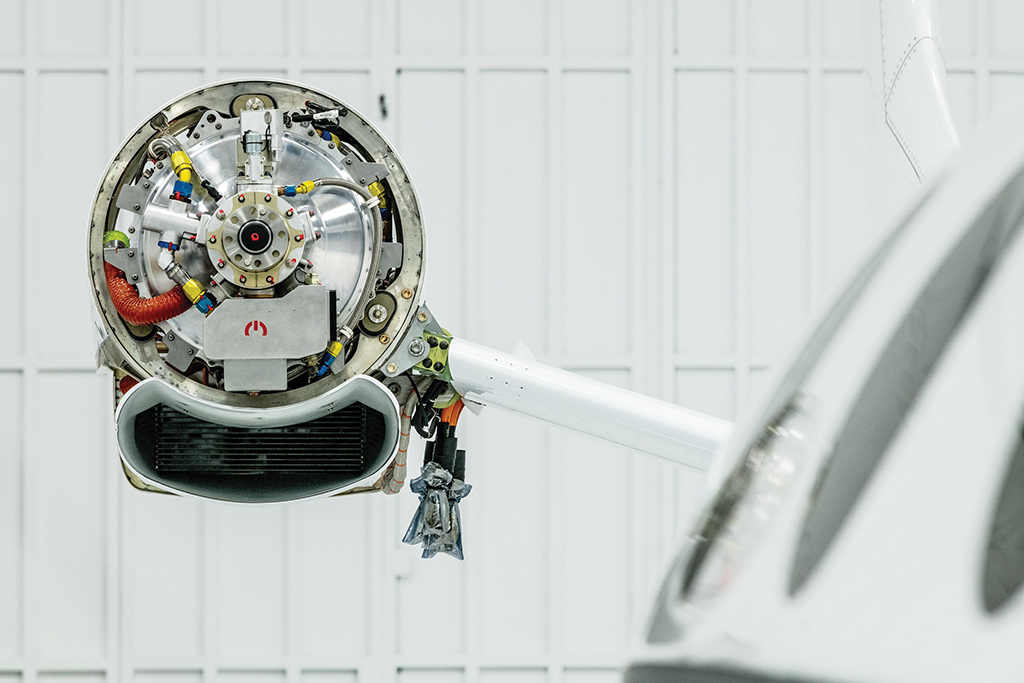

Everett, Washington-based MagniX is the first company to undertake FAA Part 33 type certification of an electric motor, with approval of its 350-kW Magni350 and 640-kW Magni650 electric propulsion units (EPU) now targeted for mid-2025, Chief Technology Officer Riona Armesmith says.

Retrofits are the easiest path to market for the startup—using already-certified aircraft as the initial platforms allows MagniX and its partners to focus resources on certification of the electric engines and their integration onto aircraft. It also provides operators and lessors of older, often out-of-production aircraft types a path to improve the sustainability and rebuild the value of their fleets.

MagniX has completed the planned final design iteration on its EPUs and is building an engineering unit that will go through a full suite of tests while the conforming hardware for certification is being built. “Parts are going through process inspections or witnessing by the FAA at this moment,” Armesmith says.

As certification progresses, the EPUs are gaining flight-test experience on Harbour Air Seaplanes’ eBeaver and Tier 1 Engineering’s e-R44, both retrofits, as well as Eviation’s clean-sheet Alice. Universal Hydrogen recently flew a De Havilland Canada Dash 8 testbed with a MagniX motor powered by a hydrogen fuel cell, and MagniX itself is modifying a Dash 7 into a hybrid-electric demonstrator for NASA.

Multiple companies have announced plans to obtain supplemental type certificates (STC) for electric, hybrid- and hydrogen-electric retrofits using MagniX EPUs, starting with the popular Cessna Caravan. But they need MagniX to secure type certification before they can proceed with an STC.

“Certification of the Magni350 and Magni650 EPUs is the top-down priority throughout the entire company,” says Armesmith, who joined MagniX in 2021 from Rolls-Royce. “In parallel with that is the Electrified Powertrain Flight Demonstration [EPFD], which was launched by NASA to knock down some of the barrier risks to certification of electric propulsion. So they are highly complementary.”

MagniX was awarded the $74.3 million EPFD contract in September 2021 and is working with aircraft certification specialist AeroTEC and Canadian regional airline Air Tindi to modify a De Havilland Canada Dash 7 to hybrid-electric propulsion. The demonstrator is planned to fly in 2025.

“That program is really helping with certification, with the development of regulations and standards,” Armesmith says. “Getting an experimental flight approval under NASA is quite a high bar. It’s not like an FAA experimental flight ticket. It’s not to the point of certification but probably one bar below that.

“Everything that we do under the EPFD program is aligned [with certification] in the company, and they benefit each other,” she says. “So outwardly, it looks like we’ve got a lot on—many different things coming at us from different directions—but internally they are well aligned.”

For the STC programs, MagniX is supporting its partners. “We’re not applying for the STC ourselves. We’re not an airframer, so we work with the likes of Harbour Air to support them with their STC program,” Armesmith says. “But frankly, they are waiting for us to have a type certificate.”

MagniX finds itself in an unusual situation for a propulsion company, as it has several engines in flight testing on different platforms before it has a certified product. “We’ve had the opportunity to wring out teething issues before certification, which doesn’t normally happen,” she says.

Harbour Air’s eBeaver, a modified De Havilland Canada DHC-2 Beaver, flies almost every week, and MagniX has completed the first teardown inspection and return to service on an EPU for that program. Both Harbour Air and Tier 1, with the modified Robinson R44, have begun point-to-point test flights at usable ranges, Armesmith tells Aviation Week.

Much of MagniX’s learning from these test programs has been on installation and maintenance, making each new application easier. “We’ve got to the point where it doesn’t take us as much internal effort to get somebody else flying because the documentation is good,” Armesmith says.

“The installation manual is good, as are the operations and maintenance manuals,” she says. “You essentially get handed an interface document, all the manuals underneath, and then we help with the integration. But every one is easier now, and we have a team that goes and helps support getting them up and running.”

Each demonstrator project also is teaching MagniX something new because each customer wants to use the equipment differently. Universal Hydrogen, for example, is powering a Magni650 EPU with a hydrogen fuel cell, not a battery. And while both provide electrical power, they have different characteristics.

“We say we are electron-agnostic, but a fuel cell stresses our EPUs significantly differently to a battery,” Armesmith says. “We’ve had to change and align our control system to handle it.

“The ramp rate of a fuel cell is not the same as for a battery,” she notes. “In a fuel cell, the more power you pull from it, the lower the voltage drops. It stresses your EPU in a way you would only get with a battery at very low state of charge—which is not a condition we often encounter because we’re always holding reserves.”

This breadth of application has resulted in changes to the EPU, control system and software, so it is now capable of handling both analog and digital commands, fuel cells and batteries, retrofit and forward fit, even different installation orientations. “When you go from an R44 to a Dash 8, it’s a vastly different spectrum of aircraft,” she adds.

What has been learned about installation and maintenance has been fed back into what MagniX hopes will be the final design iteration on the EPU. Most of the changes have been in software. “People say electric motors are much less complex than gas turbines,” Armesmith says. “And that is true physically, but functionally, and in software, I would say [motors] give [turbines] a run for their money.

“Controlling permanent magnet machines is complex,” she continues. “And the software around extremely fast-acting protection systems that can get ahead of an electrical fault is very complex. A lot of our development recently has been around that.”

While most early applications are targeting the use of Magni650s to replace the Pratt & Whitney PT6A-class turboprops that power 9-19-seat aircraft, Universal Hydrogen is aiming at 50-70-seaters. The Dash 8 testbed flew on March 2 with a 1-megawatt powertrain, while a 2-megawatt system will be certified in the ATR 72.

“One of the complexities, or benefits, of a motor is that its power depends on what speed you operate at,” Armesmith says. “What we will put on the Magni650 type certificate is 640 kW, and we’ll guarantee that over a 1,900-2,300-rpm speed range.

“For Universal Hydrogen, we’re running it faster, and we are getting 750 kW out of it,” she says. Power capacity is tied to cooling capability, and “it makes sense [for Universal Hydrogen] because they can deliver quite cold coolant, but it will mean quite a big heat exchanger for other applications,” she notes.

MagniX has entered the battery system business with the NASA EPFD program and has announced plans to do the same with fuel-cell systems. “We see that there’s an advantage to having an end-to-end integrated propulsion system,” Armesmith says.

Especially with early retrofits, the company is working with operators—not airframers—and offering a complete system makes it easier for these types of customers. “And we’re realizing we can show a benefit at the platform level from integrating these things,” she says.

“It’s quite exciting at the moment in terms of where battery cell development is going,” Armesmith says. “We’re thinking about how we integrate this, definitely at the pack level, probably at the module level.”

For fuel cells, the focus is on system-level integration and the balance of plant, but Armesmith says MagniX probably will have to become involved in the fundamentals of fuel cells “because they really need a push.”

Editor's note: This story was updated to clarify that Universal Hydrogen's Dash 8 testbed flew on March 2.